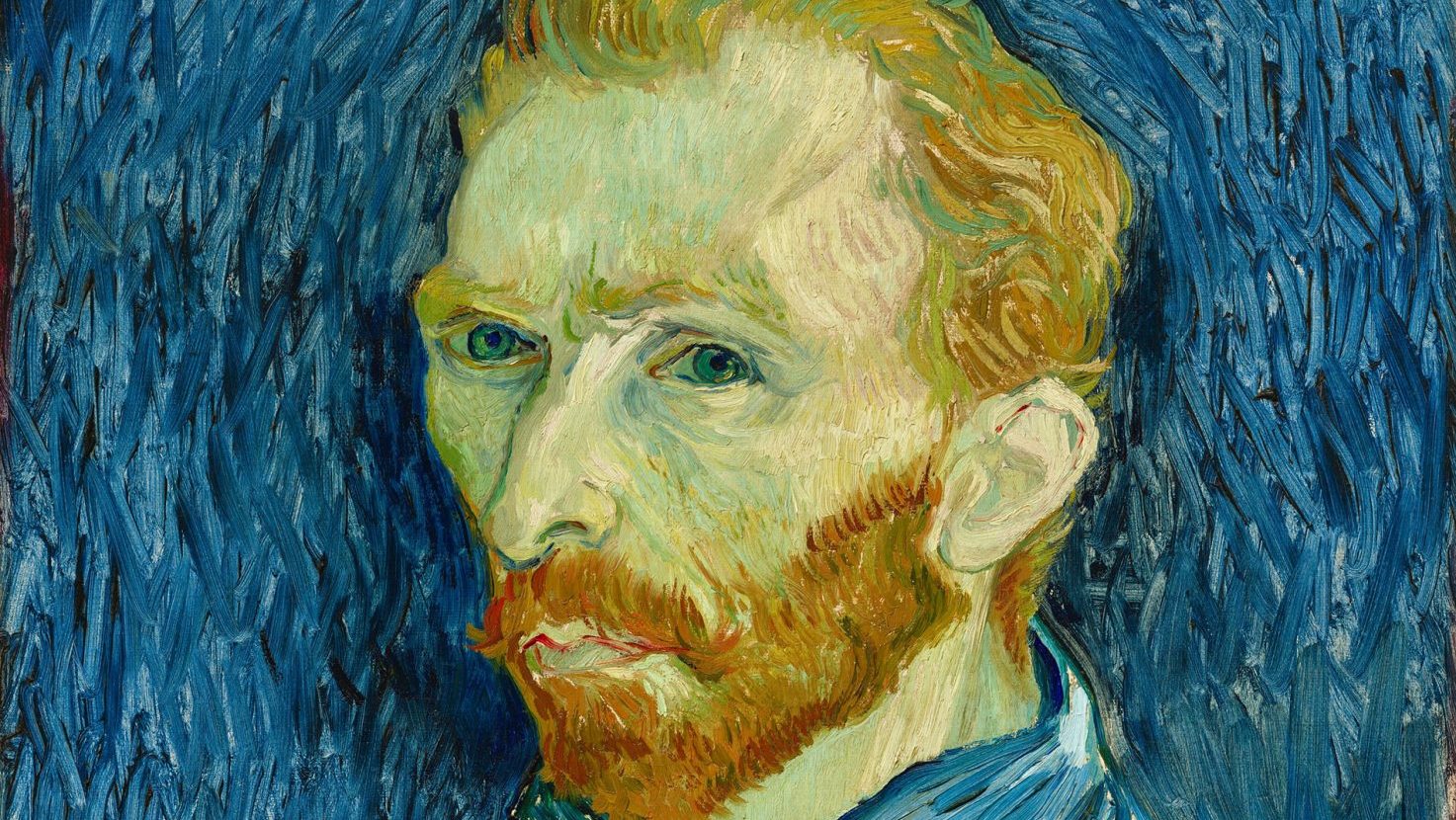

“It is a sacrifice for the sake of Vincent’s glory,” wrote Jo van Gogh-Bonger in 1924, on the uneasy sale of Sunflowers (1888) to the National Gallery in London. It was painted by her late brother-in-law, the Dutch artist Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890).

One hundred years after the transaction, the painting is the public’s favourite work in the National Gallery. And in its shops, both in Trafalgar Square and online, Van Gogh’s artwork is licensed for Sunflower T-shirts, tote-bags, notebooks, umbrellas, pens, posters, postcards, which connect people to possibly the most famous artist in the western world and one of the most famous art galleries in the world.

Is this the “glory” that was envisaged? And what was the “sacrifice”?

In January 1924, the sacrifice Jo made was the sale of the Sunflowers painting that had hung in her home for over 30 years. The painting was special, a visual connection to her late husband, Theo van Gogh and his brother, Vincent. She had offered to loan, not sell the work.

In a letter to the National Gallery’s director of British art, Charles Aitken, who wanted it, she wrote: “I have tried to harden my heart against your appeal; I felt as if I could not bear to separate from this picture I had looked on every day for more than 30 years…” But she accepted, “for the sake of Vincent’s glory”.

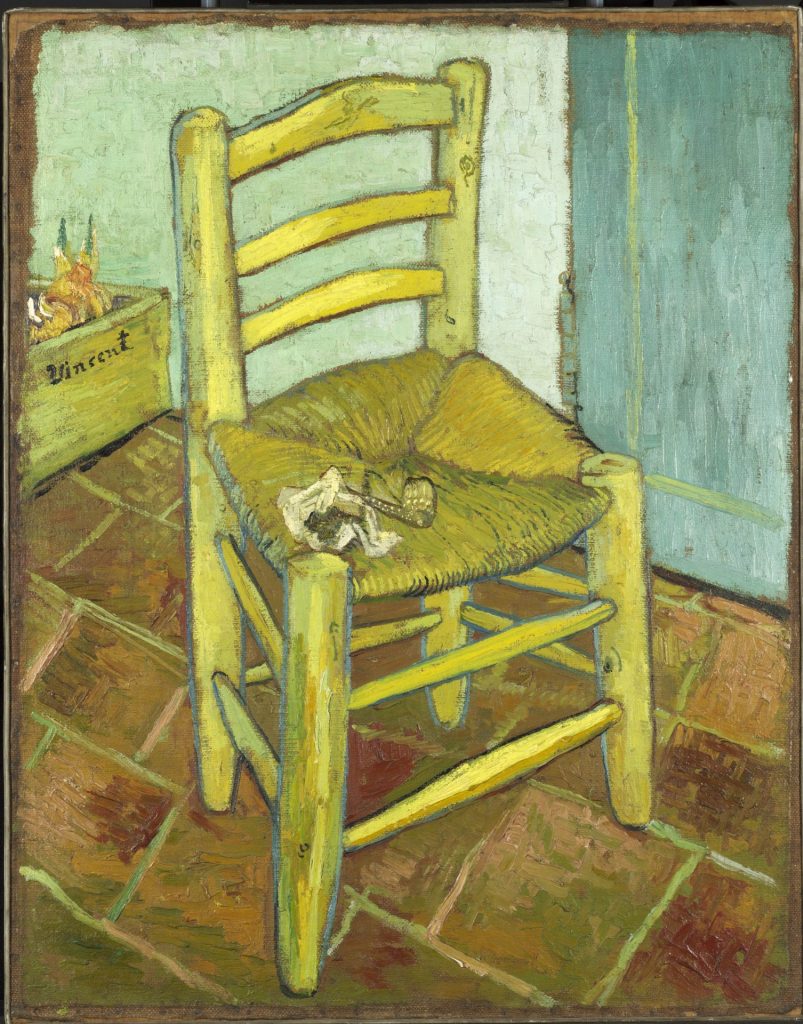

What her letter of January 24, 1924, did not refer to was the continual wrangling involved to get a fair price for a Van Gogh painting over 30 years after his death. Initially, Aitken’s aim was to buy Joseph Roulin (1888), a portrait of a postman and friend to Vincent, and Van Gogh’s Chair (also 1888), both painted in Arles, in the south of France.

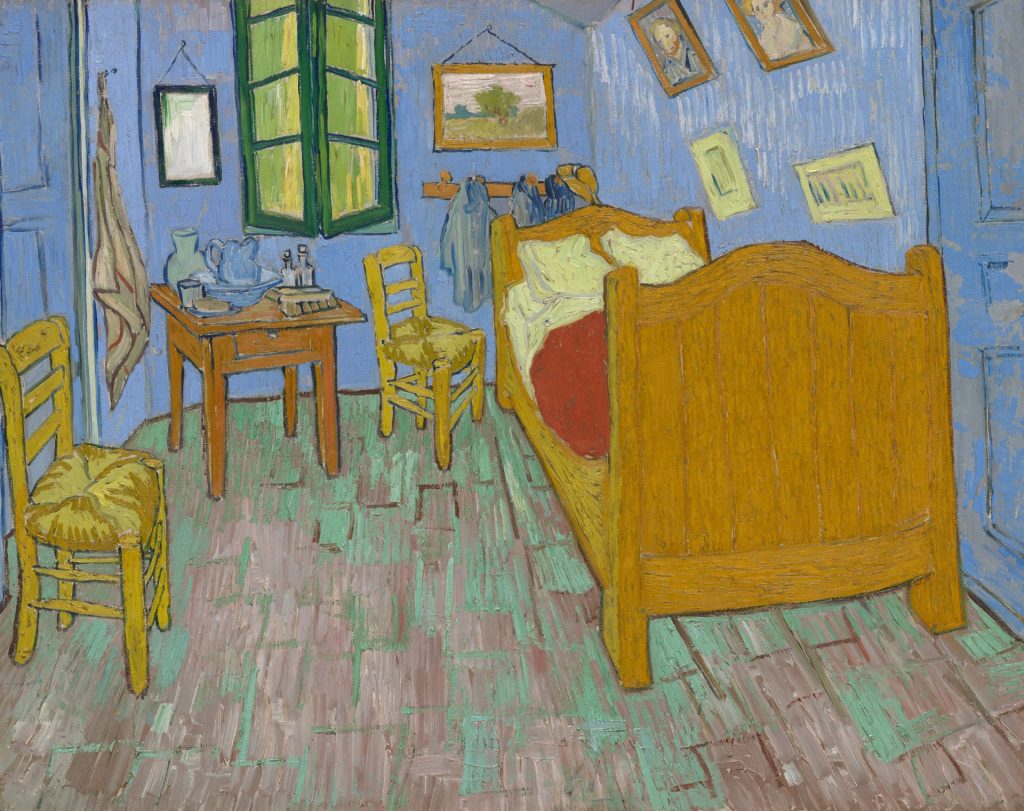

Jo wanted 10,000 guilders for the Roulin portrait. Aitken offered 9,000 guilders, and 8,000 guilders for Van Gogh’s Chair, plus a loan request of three more Van Gogh paintings from 1888, Sunflowers, The Bedroom and The Yellow House (The Street), which were on exhibit at the Leicester Galleries in London.

Jo knew the value of Vincent’s art, but recognised the added value of it hanging in a national gallery. The loan of three works was agreed, but she would not lower the sale price of the Roulin portrait.

Meanwhile, the director of the National Gallery, Charles John Holmes, pitched his opinion that the three works offered for loan were not masterpieces, referring to them as “remnants”. Nevertheless, the directors wanted to have artworks by Van Gogh in the gallery.

The double purchase of Joseph Roulin and Van Gogh’s Chair was agreed at the original price, but the Roulin portrait was then returned. The trustees of the Courtauld Fund, purchasing it for the National Gallery, thought that the postman’s beard was “too funny” and would not fund the sale.

In her letter, Jo agreed to take back the “Postman” and exchange the Sunflowers loan for the same sale price. Four weeks later the postman’s portrait was sold to Galerie Thannhauser in Munich for 10,000 guilders.

This year the National Gallery celebrates its 200th anniversary, marking it with a “once-in-a-century” exhibition of 60 artworks, both paintings and drawings: Van Gogh: Poets & Lovers. Van Gogh’s Chair and Holmes’s “remnants” – Sunflowers, The Bedroom, and The Yellow House – are included. Today they are near-priceless works of art to which the National Gallery owns the copyright, receiving the proceeds from merchandise and when others license the images.

The exhibition’s focus is on the period from February 1888 until May 1890 that Vincent spent in the south of France, first living in Arles, followed by a year as a voluntary patient at the asylum hospital of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. The title relates to the portraits The Poet and The Lover (both 1888), which symbolise the people he had met.

Two of seven paintings of sunflowers he created will be shown as part of a triptych that he had imagined in spring 1889, described in a letter to Theo. At centre will be a portrait of Madame Augustine Roulin, the postman’s wife, as La Berceuse (Lullaby: Madame Augustine Roulin rocking a Cradle,1889).

Winding back to June 10, 1890, Vincent had left the asylum hospital in Saint-Rémy in May.

He wrote from his new location in Auvers-sur-Oise, north of Paris, to Theo: “One day or another, I think I’ll find a way of having an exhibition of my own in a café”.

On July 30, in Café de la Mairie (now Auberge Ravoux) the café-restaurant where he rented an attic room, bunches of yellow flowers and his latest paintings – some still wet – filled the ground floor dining room. They surrounded his coffin.

Theo and friends were there to mark the end of life of a barely-known artist, who had shot himself on the evening of July 27 after a day spent painting. He died on July 29 and was buried the next day, in Auvers. He was 37 years old and had sold only one painting during a decade as an artist, despite having created over 800 paintings and nearly 1,300 works on paper.

The vast collection of paintings and drawings were now the property of Theo, who had paid his brother for them in a long-term agreement of financial support. Six months later, in January 1891, Theo died from a syphilis-related disease. He had been married for two years.

Jo and their year-old son, Vincent, named after his uncle, now owned hundreds of works created by her brother-in-law that were unsaleable. In addition, she had more than 800 letters from Vincent to Theo, family and friends. From this family tragedy, she turned unknown artworks and private letters into marketable commodities. She contacted art groups and art dealers, to promote and sell the legacy she had inherited.

The “glory” that Jo referred to, in her letter to Charles Aitken, was recognition for the avant-garde post-impressionist art her brother-in-law had created. It didn’t happen overnight.

The history of her commitment is told through records of negotiations with dealers and galleries. The National Gallery presentation includes the fabulous Starry Night over the Rhône (1888). The painting’s history links to a much earlier showing at the fifth exhibition of the Société des Artistes Indepéndents in 1889 in Paris. It received a positive review from a distinguished art critic, Félix Fénéon, but remained unsold.

Jo later placed it in a solo selling exhibition in Paris in December 1896, organised by French art dealer Ambroise Vollard. A shrewd man, Vollard was known in half-jest as an art-vole (art thief), for the low prices he offered little-known painters. Fifty-six paintings, another 56 drawings and a lithograph were chosen. Starry Night over the Rhône was given the highest sale price of 1,000 francs by Jo.

Vollard complained that she had raised the prices. The show failed. The painting sold three years later. To put the value of that Van Gogh painting in perspective, at auction in 1990 Portrait of Dr Paul Gachet fetched $83m. It would be valued at hundreds of millions today.

A factor in Vincent’s “glory” was the publication in Dutch of Vincent van Gogh: Brieven aan zijn broeder (Vincent van Gogh: Letters to his Brother) in 1914, in three volumes, edited by Jo and translated in German the same year. An English translation would wait until 1927, but the original created a wider public interest in the artist and the man.

Later in 1914, Jo had Theo’s body exhumed from Soestbergen cemetery in Utrecht, where it had lain for 23 years, to be reburied alongside Vincent’s grave in Auvers-sur-Oise. Was this a marketing strategy? The letters – over 800 – that she collated and published brought Vincent and Theo back to life. It is this connection – his life through letters – that many people seek to find Vincent, in locations beyond the galleries.

After Jo’s death in September 1925, her inheritance became the property of her son, Vincent. In 1962 he gave 209 paintings and 490 drawings to the Vincent van Gogh Foundation. They became the core works of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, founded in 1973, which receives more than 2 million visitors each year. It is one of 23 locations in Europe related to Van Gogh’s life.

In London, the non-profit Van Gogh House in Brixton opened to the public in 2019. It is the boarding house where he lived in 1873-74, years before becoming a painter. It has artist residencies, and many visitors seeking Vincent.

In North Brabant where he was born and raised, the Van Gogh National Park receives formal status this autumn. The 100,000-hectare region, with 1.5 million inhabitants, melds nature reserves and agricultural landscapes with towns and cities the artist knew. The park, with three Van Gogh museums and 46 Van Gogh monuments, gets 50,000 visitors a year.

Within it, the Van Gogh Cycle Route of 435km and five 20km hiking trails are used by millions, including residents. Now, a vast floral “painting” of Sunflowers is growing in the area between Zundert and Etten-Leur where Vincent used to walk. In the Year of the Sunflower in the province of North Brabant, it is a symbol of “friendship, hope and optimism” connecting Van Gogh’s birthplace to the National Gallery’s Sunflowers and exhibition.

“Vincent van Gogh’” remains a global attraction. The virtual reality Van Gogh: The Immersive Experience, a light-and-sound spectacle, has been touring worldwide since 2017, taking his art outside the galleries to an audience of more than 5 million people. Today there is no copyright on Van Gogh’s art, except on the artworks that individual galleries own.

The descendants of Van Gogh receive no money from his legacy.

Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers is at the National Gallery, London from September 14 until January 19, 2025. Further reading: Jo van Gogh-Bonger: The Woman Who Made Vincent Famous by Hans Luijten (translated by Lynne Richards), Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2023; first published in Dutch, 2019