Nicola Sturgeon, Scotland’s first minister, is on manoeuvres. She has crafted a power-sharing alliance with the Scottish Greens, which gives her a majority at Holyrood, burnishes her green credentials and moves her one step closer to IndyRef2 and the holy grail of tartan independence.

The leader of the Scottish National Party is prodigiously talented, deeply crafty and impossibly tenacious. A politician to her fingertips, she conveys strength but she also connects with her fellow Scots at an emotional level. She drives English Tories up the wall precisely because she is so tuned in and agile.

Sturgeon’s idée fixe is that social democratic Scotland, cast out of Europe by an ultra-nationalist, rightwing, mainly English Brexit, should take its place alongside other small states such as Ireland, Denmark and Finland.

To unionists, this is heresy from an ungrateful junior partner. But that misses the point. Secession from a greater power (or a union) is not about loyalty. It isn’t a balance sheet exercise. It’s not about numbers. It’s about how people feel.

Breaking away from the UK, or the EU for that matter, is about tapping into a mood and giving it a recognisable shape. That’s the one big thing that Dominic Cummings understood. He was not the first.

In October 1706, England sent a spy to Edinburgh to report on the dying days of an independent Scotland. Daniel Defoe, an immensely talented reporter and novelist (Robinson Crusoe and Moll Flanders), possessed an exceptional eye for the human condition and its weak spots.

Defoe’s task was to sway Scots, many of whom were bitterly opposed to the loss of sovereignty, in favour of a union with England. Like Cummings, Defoe (though infinitely more talented) was a propagandist, a stirrer. He understood then, as Cummings did in 2016, that the power of emotion, manipulated without limit or scruple, can make history.

People don’t like being told what to do. Sturgeon too gets this. She has spent half a lifetime crafting a breakaway platform by astutely melding Scottish aspiration and resentment.

Scottish desire for self-rule continues to pulse strong and deep. Many English, among them Boris Johnson, profess themselves baffled by this and by the resentment of the Auld Enemy south of the border.

The only surprise is that Johnson finds this surprising. Surely he, of all people, can empathise with the impulse to be free of what one side sees as a bad marriage even if the other doesn’t feel the same.

Independence from Brussels was an itch that Britain could not stop scratching. The yearning for a free Scotland is an ancestral instinct that has survived the 300-plus years since the Acts of Union in 1707.

Resentment at real or imagined slights by a central power is the hallmark of secessionism: the feeling of being patronised and ignored; a minority’s rage at being politically hobbled and consistently outvoted on national issues that affect them.

Brexit, Scottish independence, Catalan and Flemish separatism, deep down it all comes from the same place. Secession may sometimes be a miscalculation, even a precursor to disaster, but it doesn’t come out of nothing. It can be manipulated but it is not made up.

The world map is not frozen in time and there is no good reason why it should be. From the separatist’s vantage point, breaking away is a perfectly rational response to the feeling of being assigned a lower status than they deserve, or add to an atavistic fear that their culture is being swallowed up.

Separatism is everywhere, except Antarctica where the only permanent residents are penguins: Scotland, Quebec, Italy’s Lega Nord, Kashmir, Chechnya and so on.

Which raises a question: why is the integrity of the UK any more sacrosanct than, say, that of the former Yugoslavia, Spain or Belgium, where the pandemic has radicalised an increasingly secessionist Flanders? Does the ritual of crown and country, or the mysteries of our unwritten constitution, bind us in some special way?

Does it make Britain less susceptible to the centrifugal forces that afflict many modern nation states? Brexit and the stubborn survival of Scottish nationalism suggest not.

Those who argue passionately against a break-up of the union, Westminster’s “better together” advocates, including Gordon Brown, make a strong argument. But they also face a fundamental problem.

This thing we call Great Britain, the British experiment, has so far been, at best, only a partial success. Team GB remains, after three centuries, an inconsistent performer. Why else would unionists keep trying to redefine it?

To paraphrase the central question in Gavin Esler’s excellent book How Britain Ends, better together with whom and for what purpose? This is reflected in changing attitudes. That elusive “British” identity remains fleeting.

Most Brits, including those with ancestral roots in these islands, now identify equally with their British and national identity. And more than one-third, and rising, identify as more Scottish, Welsh or English than British.

Massimo d’Azeglio, the Piedmontese statesman and advocate for Italian national revival, said: “We have made Italy. Now we must make Italians.” Judged by this yardstick, project Great Britain is still a work in progress – stuck half-in, half-out of its intended destination wherever that may be. Stubbornly centralised, the corridors of power are still enveloped in a post-colonial fog.

Scots who favoured the union in 1707 were willing to trade (much) of the country’s sovereignty in return for free trade with England and its colonies. For those who stood to gain – the elite – it was a price worth paying.

Brexit has stood that equation on its head. Leaving the EU has robbed Scotland of the benefits of union with England because both nations have quit the most prosperous advanced market in the world.

A breakaway Scotland would represent a huge constitutional upheaval with enormous risks for all concerned. It would not be, any more than Brexit, a magic door to the future. It would be a high-risk roll of the dice.

The economic arguments against Scottish independence are laid out passionately, if a little partially, in John Lloyd’s polemic Should Auld Acquaintance be Forgot: The Great Mistake of Scottish Independence. There would, as Lloyd argues, be no guarantees of prosperity or even re-entry into Europe.

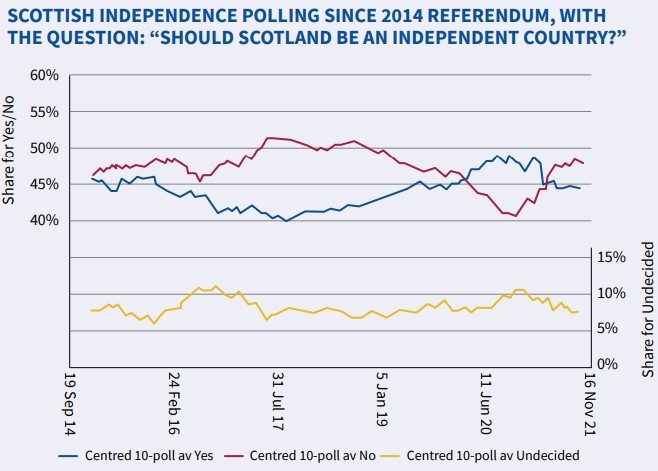

Scottish independence is by not a foregone conclusion. But neither is it a dead duck. It is all to play for.

How countries manage the secessionist impulse varies greatly: Canada has stayed one step ahead of Québécois secessionism through a combination of inducement and devo-max. The leading imperative of Canada’s federal government is to hold the country together. Still, it is not settled.

Spain throws Catalan nationalists in jail. Denmark, when Iceland voted to secede in 1944, just said “Goodbye and God speed”. It had little to lose.

Scottish independence, on the other hand, would slice off one, if not two, limbs from Britain.

Britain’s Trident nuclear subs for one would have to find another home.

Johnson, with his tin ear, is perhaps the worst possible candidate to salvage the union. He cannot see how Brexit, which the majority of Scots opposed, has fundamentally altered the calculus. Or perhaps he does but, like many of his fellow Tories, is willing to sacrifice Scotland for eternal Tory rule in England.

The danger now is that both the SNP and the Tory government, postimperial unionists to the marrow, will miscalculate their response to each other.

Johnson would be foolish to just say “no” to another referendum. This will feed the Scots’ sense of being marginalised.

The urge to secede in Scotland, like Ireland a century ago, will not just evaporate. It is in the DNA.

Sturgeon, on the other hand, would be crazy to go for a breakaway with anything less than a big majority which, for the foreseeable future, seems unlikely.

Scottish independence by a whisker would be as hopelessly divisive as Brexit has been. Tinkering won’t work. Britain needs to be re-imagined as a genuine partnership of nations.

Such a new constitutional framework, perhaps a federal one, must find a way of drawing the sting for English ultra-nationalism by giving England its own voice so that it stops confusing it with Britain’s.

Alain Catzeflis is a former news editor of the Financial Times.