When Louis XIV of France chose to build his palace and gardens on a dusty elevated plain some 12 miles west of Paris, he was consolidating his status as Sun King. Enormous sums of money were spent and thousands of labourers employed to create at the site of his father’s hunting lodge, this Xanadu at Versailles, synonymous with lavish spectacle, conspicuous consumption and the bending of nature itself to the Sun King’s absolute will. Meanwhile, back in the French capital, ordinary Parisians burdened by taxation and disease starved.

This state of affairs continued through the subsequent reigns of Louis XV and his son, Louis XVI, until the 1789 revolution that put an end to Versailles as a royal residence, saw the execution of the monarchs and an auction of their belongings. Little remains now of Queen Marie Antoinette’s innumerable dresses.

The new exhibition at London’s Science Museum, Versailles: Science and Splendour, opens with the portraits of these three kings, but follows the less-familiar story of what did survive, namely the science. The Academy of Sciences and the Paris Observatory, established under the auspices of Louis XIV’s first minister of state, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, lured the greatest minds from across Europe to Paris and dedicated generous resources to encourage innovations and the making of scientific instruments in service to the French State. Both institutions exist to this day.

On display are objects that dazzle, among them a watch made by Abraham-Louis Breguet. The horologist arrived in Versailles from Neuchâtel to undertake an apprenticeship at the age of 15, before setting up a watch-making business in Paris.

Breguet’s 160th commission, the No 160 “Marie Antoinette” watch, has its own dedicated vitrine at the Science Museum. This small gold watch stands in front of a circular mirror that reflects its workings, revealing the mystery of its 823 parts: its cogs, wheels and levers, its sapphire points of friction, its tulip bud fingers and elegant numerals on a rock crystal face.

I wondered at the travel arrangements involved in bringing the piece over from its permanent home in the LA Mayer Museum for Islamic Art in Jerusalem and the cost of the insurance. Most of all, I longed to hear it tick.

In 2016, aged 92, the game show host Nicholas Parsons, a lifelong horology enthusiast, narrated a television documentary entitled The Incredible Story of Marie Antoinette’s Watch. In it he describes the genesis and troubled history of “the most precious piece of clockwork in the whole world”: how Breguet received the commission in 1783 from someone whose identity is unknown (though suspected to be the Queen’s admirer, Axel von Fersen); how it took 44 years to create, by which time the queen had been guillotined and Breguet himself had died; how the watch passed to his son, who completed it in 1827; how in 1983 it was stolen from the museum in Jerusalem, then recovered in 2006.

When Nicholas Parsons holds the No 160 Marie Antoinette in his white-gloved hand, he says with emotion, “This is a special moment in my life…” As if in response, the watch begins to work.

The No 160 Marie Antoinette looks positively modest compared with the swaggering ostentatiousness of The Creation of the World, an astronomical timepiece designed by Claude-Siméon Passemant and presented to Louis XV in 1754. The drama of its Rococo sunburst clock nestling in golden clouds above a swirling silver cascade carrying spheres and a mechanism to demonstrate the solar system has to be seen to be believed. It echoes the extravagant ornamental luxury of the interior rooms of the Versailles palace, in contrast to the strict clipped geometry of its gardens outside.

Recalling the travails of Breguet, it took André Le Nôtre, Louis XIV’s landscape architect, 40 years to transform the unpromising marshland and meadow surrounding the palace into terraced gardens fit for a king. The feat of engineering genius required to create the fountains “must seem incredible to those who will reflect that there was not a drop of water at Versailles,” noted Jean Donneau de Visé in 1686.

To add salt to the challenge, the palace was situated on an elevation. But the king wanted fountains – sprays, jets and plumes of sparkling water – and that is what he got, after a fashion.

The wooden model of the Marly Machine illustrates how a system of gigantic paddle wheels activating 260 hydraulic pumps forced water 162 metres uphill from the River Seine in the Yvelines Department to the 2,000 fountainheads at Versailles. For all the toiling man-hours involved in its construction, the ingenuity applied to the innumerable problems it faced, the progress made in the manufacture of seamless cast-iron pipes, the Marly Machine was prone to breakdown and water could not be replenished quickly enough to make the garden features work continuously.

Some visitors were unimpressed. “The violence done to nature is everywhere repellent and disgusting,” wrote disgruntled nobleman Duc de Saint-Simon in his report on life at court.

There were, however, happier horticultural achievements. The painting of a flamboyant pineapple in a pot by Jean-Baptiste Oudry is a tribute to France’s first pineapple grown in a hothouse at Versailles and gifted to Louis XV on Christmas Day 1733.

When Jane Parminter, an English lady on a grand tour of Europe, visited Versailles in 1784, it was the royal menagerie that impressed her most. Her encounter with “the buffalo, the rhinoceros, the pelican, the panther, an African sheep with no tail, and a great variety of other things” interested her far more than the sighting of the king and queen in their carriage. As representative of the menagerie, an immense taxidermied Indian rhinoceros is among the exhibits.

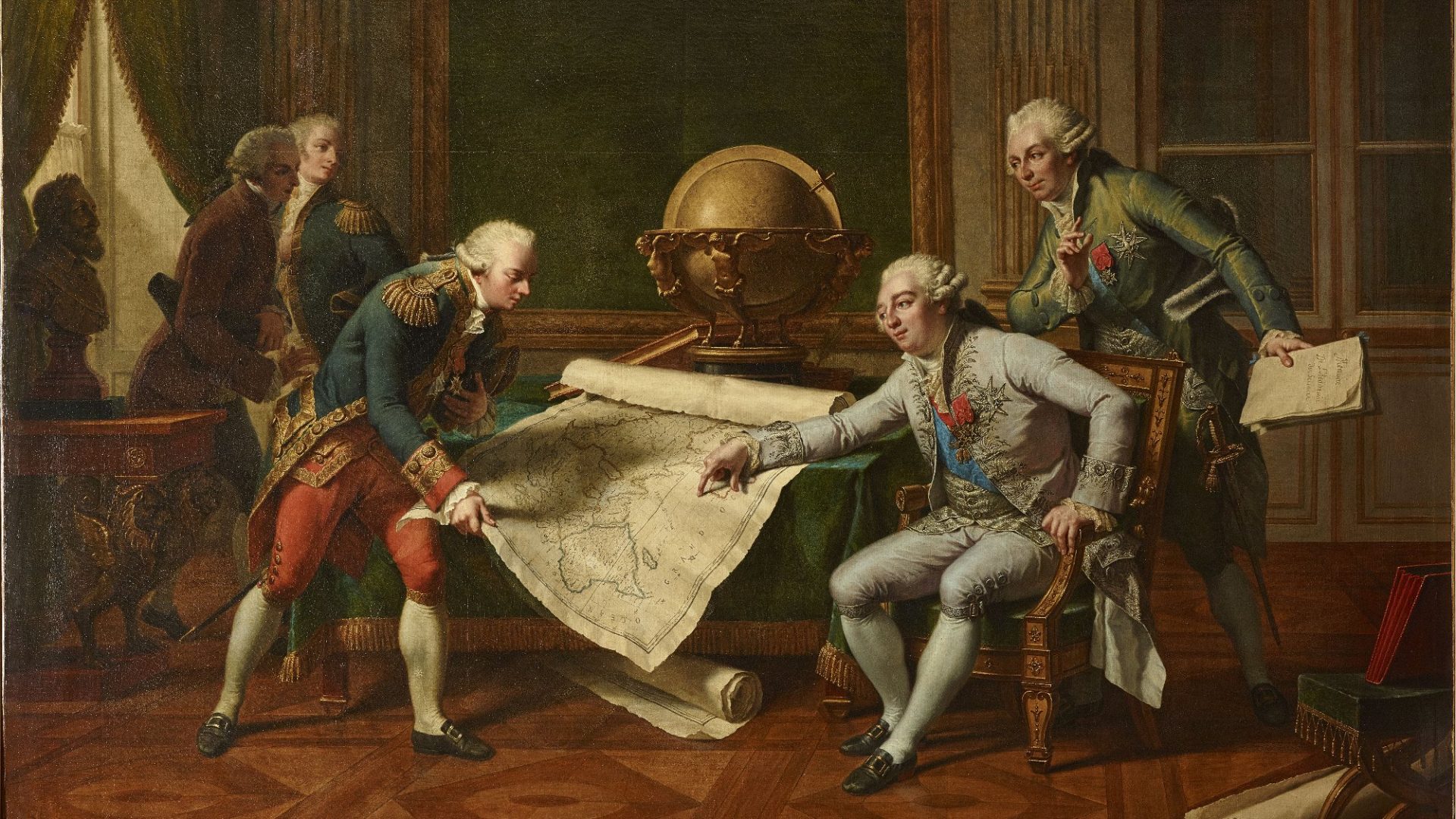

Versailles: Science and Splendour presents the scientific advancements of the French court, which travel down the centuries to meet our own. The exploration of space from the Paris Observatory resulted in the mapping of the moon’s cratered surface by Jean Dominique Cassini and the discovery of four of Saturn’s moons. In medicine, Louis XVI’s successful inoculation against smallpox was feted by fashionable ladies sporting spotted ribbons in their ostrich-feathered hats. Both find parallels today.

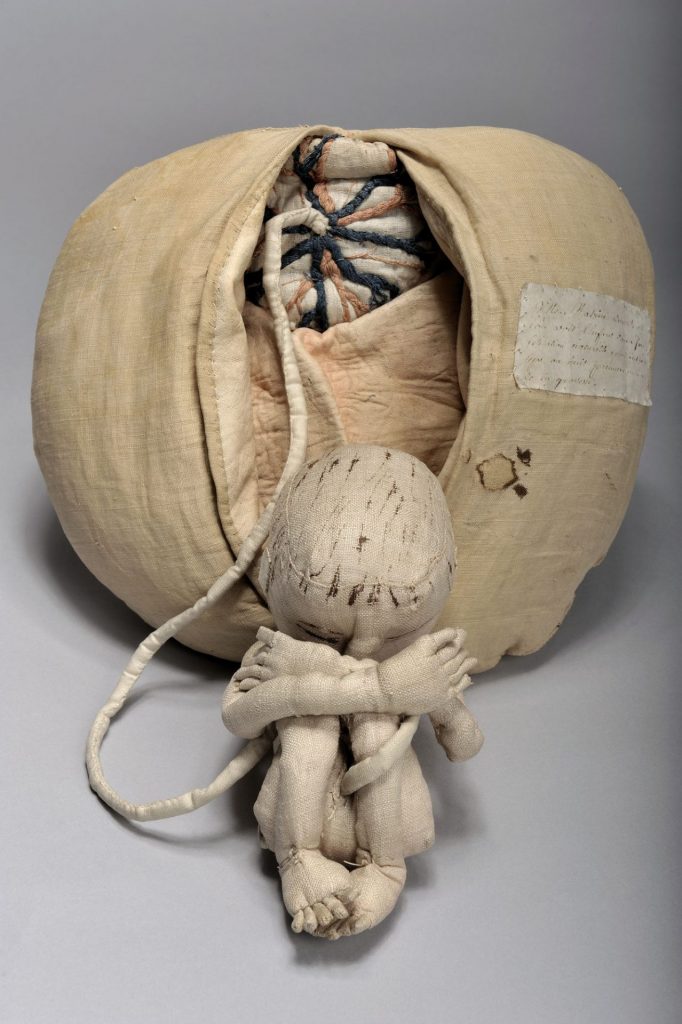

The exhibition reflects current trends to illuminate the contributions made by women (Marie Antoinette gives way to Madame du Coudray, who trained thousands of midwives across France in obstetrics) as well as less savoury aspects, such as minister Colbert’s role in the slave trade. There are some absences, for example, Louis XIV’s military engineer Marquis de Vauban does not feature and, with the exception of the water and firework animations, the exhibition design and display captions rarely capture the excitement surrounding the science and the grandeur of the setting.

More important, however, is how the Paris Observatory and the King’s Garden (now the Museum of Natural History in Paris) lent their objects to this exhibition, a reminder of the value of international partnerships and the benefits of collaboration in scientific research and innovation.

Versailles: Science and Splendour is at the Science Museum, London until April 21, 2025