On any given morning in the 1930s or 1940s, children walking to St Patrick’s School in Toxteth, Liverpool, would likely have seen the strange sight of a Nigerian pastor, wearing a Kufi cap, with a patchy white beard, dressed neatly in somewhat worn clothing, asking them if they had had breakfast. If any of the children said no, the pastor, named Daniels Ekarte, would invite them into a pair of roughly knocked together terraced houses for some toast.

This was the African Churches Mission, founded by Ekarte in 1931, which, for 30 years, was a centre for Christian philanthropy, community development and radical Black politics in Liverpool.

Inside, the children may have seen a billiard room with a table for playing dominoes, a hostel for the homeless and a reading room. They may even have caught a glimpse of the likes of Kwame Nkrumah, the anti-colonial leader and future first prime minister of post-colonial Ghana, Jomo Kenyatta, the future first prime minister of postcolonial Kenya, the pan-African writer and communist George Padmore or the actor and singer Paul Robeson, all of whom visited this strange address at different times.

When picturing a map of the world, we are used to thinking of a spider web of borders drawn over every major continent marking out hundreds of sovereign and nominally equal nation states. The map we are familiar with is largely a product of a burst of decolonisation during the first two decades after the second world war.

At the outset of this process, however, in the 1940s and early 1950s, the exact contours of the postwar world were still to be decided, and not all would have predicted the shattering of Europe’s empires into hundreds of small nations.

Pan-Africanists, such as Kwame Nkrumah and the South African dissident Robert Sobukwe, hoped that Africa might instead become a gigantic integrated polity, a counterweight to other global superpowers. Others, such as the historian of slavery and first prime minister of Trinidad and Tobago, Eric Williams, advocated for and briefly witnessed the creation of a West Indian Federation that would unite the post-colonial Caribbean, preventing any one nation from being dependent on Europe or the United States.

The political theorist Adom Getachew has referred to these different projects as experiments in “world-making”, attempts to imagine more radical, more democratic post-colonial futures beyond the creation of hundreds of nominally independent nation states.

Rather than gradually scale up the theory of sovereign nationhood that had slowly emerged in Europe since the 17th century to cover the globe, these worldmakers sought to invert the inequalities of race and capital that structured the global order.

Liverpool was a stage on which some of these different visions for the future were thought through and contested in the 1940s. Just as the city helped forge Britain’s empire, some in Liverpool were eagerly anticipating its undoing at the dawn of the postwar world.

Many of the details of Daniels Ekarte’s early life are unknown. He was likely born in Calabar in eastern Nigeria in 1896 or 1897. Following an early conversion by the celebrity Scottish missionary Mary Slessor, he worked his way to Liverpool as a sailor, probably working below deck and arriving shortly after the first world war. Ekarte was also a prolific gambler during this period and was associated with organised crime. He once claimed that he purchased a gun with the intention of returning to Calabar to “shoot all missionaries, black and white”.

Many of these stories are embellished and some are impossible to verify. For much of the 1920s, Ekarte worked in a sugar refinery by the docks and, following a second conversion experience in 1922, began honing his skills as an itinerant minister, preaching on street corners.

By 1931, Ekarte had raised enough money from the Church of Scotland’s missions committee to buy two adjacent houses, 122 and 124 Hill Street, and turn them into the African Churches Mission to serve the growing Black community.

Ekarte’s real calling came, however, with the 130,000 Black American servicemen who passed through Britain between 1942 and 1945. On Merseyside, the arrival of Black US troops prompted some nightclubs in the area, with the support of local police, to introduce whites-only policies. These included the Rialto Ballroom on Upper Parliament Street, the Grafton Rooms on West Derby Road, the Aintree Institute in Walton, Burton Chambers near Stanley Park and Vale House in Sefton.

In making no distinction between Black US soldiers, West African seamen, the children of mixed-race couples or the technicians hired from the West Indies, these “colour bars” helped establish race as one of the clearest markers of social difference in the city.

Meanwhile, in Liverpool and across Britain, it was common for US servicemen to start relationships and father children with local women. American soldiers who fell in love with British women had to receive permission from their commanding officers to get married, permission which was invariably refused to Black GIs from an officer corps that was almost entirely white.

When the war ended, the presence of illegitimate mixed-race children prompted a minor cultural panic on both sides of the Atlantic with reports circulating of 10,000 “brown babies” in Britain (the number was likely much lower, fewer than 2,000 according to a more conservative estimate). Fearing social disgrace, many single parents of mixed-race children left their children to care homes and some local authorities hatched plans to deport mixed-race children to the US.

For Ekarte, these mixed-race children would form the basis for a radical world-making project. The pastor had long supported the Black nationalist and pan-Africanist politics of earlier 20th-century politicians and writers such as Marcus Garvey and George Padmore, the latter of whom he had hosted in Liverpool.

These thinkers called for the creation of a new, separatist homeland in Africa to which Black people across the world, but particularly those living in the Caribbean and the United States, should migrate, reversing the centuries-old Atlantic diaspora forged by European slavery.

Building on the ideas of these thinkers, Ekarte imagined that this Black homeland would be modelled on Britain’s white Dominion colonies of Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

In 1945, Ekarte announced his intention to house the mixed-race children in a new care home in Liverpool named after the US Black separatist Booker T Washington. He hoped that these orphaned mixed-race children could be trained for service in new separatist states in Africa, to which they would be transported as teenagers.

In an interview, Ekarte outlined this vision: “The Englishman trains his children for emigration to Canada and Australia. We should train ours to redeem Africa. Garvey had the right idea but he was no leader… if white people can be trained to emigrate; why not black?”

Ekarte’s plan to train hundreds, possibly thousands, of mixed-race children to become the foot soldiers for a new Black homeland may well have dated back to his creation, in the late 1930s, of an all-Black boy scouts’ troop in Toxteth that he called the Liverpool Africans.

It was a vision that had the support of leading British pan-Africanists including T Ras Makonnen, the Guyanese activist and founder of a number of restaurants and nightclubs in Manchester for Black American servicemen.

Ekarte’s plans, however, immediately fell foul of an alternative vision for Black liberation, that of the League of Coloured Peoples, a group founded in London in 1931. The League had been the primary advocate for Black civil rights in Britain and had close connections with the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) in the United States. The body was founded and led for most of its short history by the Jamaican physician Harold Moody.

It was difficult to imagine two figures more different than Moody and Ekarte. While the effervescent and bombastic Ekarte had lived a working-class life, shaped by poverty, industrial work and an absence of formal education, the rational and calculated Moody was the child of middle-class parents and had trained as a doctor at King’s College London.

Moody and the League were, from the outset, firmly opposed to Ekarte’s separatist politics. Instead, with something akin to a colourblind universalism, the League called for the integration of Black and mixed-race residents into British society.

In 1943, the League held their annual meeting in Liverpool’s Grand Central Hall, a recognition that, outside of London, mid-century Liverpool was at the forefront of Black British culture and politics. Material circulated in advance of the meeting implicitly rebuked the Black separatism championed by Ekarte: “We must make it quite clear that we are not planning to build up Harlems, either in Liverpool or in Cardiff or anywhere else. We are not aiming at segregation in any form whatsoever. Our one aim is to remove completely the Colour Bar and any stigma at present attached to our people.”

Meanwhile, in 1947, Ekarte was searching desperately for funding for his scheme and was on the verge of a breakthrough. Reports of the “brown baby crisis” had garnered considerable attention in the United States. A group of Black women in Chicago formed a Brown Babies Organising Committee that sent £3,000 in donations to Liverpool. The African Churches Mission had been featured in glowing terms in Ebony and Liberty, two of the leading 1940s African American newspapers.

In January, Ekarte sent a local activist and nightclub owner, Edwin DuPlan, to New York to try to raise £100,000 and a series of high-profile events were planned for the coming year, with the rumoured support of Eleanor Roosevelt. Shortly after DuPlan’s visit, however, Moody himself arrived in New York and torpedoed Ekarte’s plan. Moody urged local NAACP leaders not to support the pastor and warned that any money raised would not be well spent. Support for Ekarte among New York’s Black elite quickly dried up.

What’s more, it also seems likely that DuPlan – a man known to the police for conning Black sailors out of money – had been stringing Ekarte along for profit.

Although donations from the Organising Committee in Chicago continued, these were deterred the following year by a sensational article in the Chicago Defender impugning Ekarte’s operation as a “swindle”.

Despite these setbacks, Ekarte continued to house mixed-race children in Liverpool. At any given time, there were between eight and 12 children staying in his Mission building in Toxteth. The pastor also claimed to be paying for a further 21 children to be put up in private homes, 11 in Liverpool and the rest scattered around the country.

Without funding, the conditions in Ekarte’s makeshift children’s home deteriorated. In 1949, finding broken windows and not enough chairs for the children to sit on, the Home Office gave him 28 days to close. Just four days later, before Ekarte had time to lodge an appeal, his Mission was raided at dawn and the children seized while the pastor was locked in his own office.

Despite his poverty, Ekarte developed his own vernacular brand of pan-Africanism, influenced by living in a city that was at the heart of the imperial world order and by engaging with some of the foremost worldmakers of this time. At the core of this dispute was the question of how to manage the instability and violence that characterised mid-20th-century Black life in Liverpool.

For Ekarte, as for Makonnen and Padmore, the solution was to retreat to a separate homeland, a Black Commonwealth in a future post-colonial Africa. In Ekarte’s words, “The future holds nothing for [a mixed-race child] in this country; if it did one could console oneself with the reflection that although there is nothing today, tomorrow might bring something. But it is not so.”

For figures like Harold Moody and the League, however, the task was instead for people of colour to remain in Liverpool (or in London, New York or Kingston) and fight for equality and integration. Caught in the swells of these intellectual currents were the mixed-race children left behind by the upheavals of war.

Ekarte died in 1964 at the age of 67. He was buried in an unmarked public grave. In 2023, his grandson Dave Daniels Ekarte joined members of the Liverpool Black History Research Group to celebrate the laying of his memorial headstone.

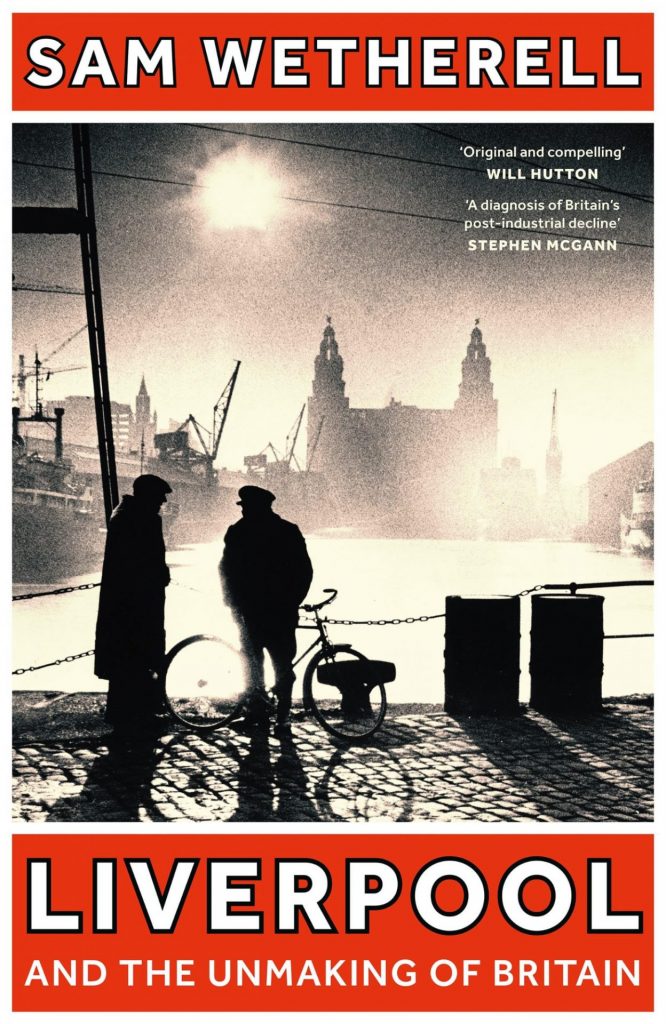

An extract from Liverpool and the Unmaking of Britain by Sam Wetherell.

Listen to the recent The Two Matts podcast to hear Matt Kelly and Matthew d’Ancona discussing the book with Sam