A few weeks ago I wrote about the extraordinary level of scrutiny greeting Sally Rooney on the publication in September of her novel Beautiful World, Where Are You. An author of fiction coming under such an unforgiving spotlight is a rare thing but for Rooney the glare only intensified when she announced last month that she had turned down an offer from Israel to translate her new novel into Hebrew.

Citing her support of the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement, which promotes a cultural and economic refusal to engage with the state of Israel, Rooney said: “Earlier this year, the international campaign group Human Rights Watch published a report entitled A Threshold Crossed: Israeli Authorities And The Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution. That report, coming on the heels of a similarly damning one by Israel’s most prominent human rights organisation B’Tselem, confirmed what Palestinian human rights groups have long been saying: ‘Israel’s system of racial domination and segregation against Palestinians meets the definition of apartheid under international law’.”

Her first two novels, Conversations With Friends and Normal People, are both available in Hebrew, through the Israeli publishing house Modan who offered to do likewise for Beautiful World, Where Are You, an offer Rooney declined.

“The Hebrew-language translation rights to my new novel are still available and if I can find a way to sell these rights that is compliant with the BDS movement’s institutional boycott guidelines, I will be very pleased and proud to do so,” she said.

Unusually for social media, when Rooney’s decision emerged things immediately got wildly out of hand.

Rare nuggets of sober commentary were swamped by a relentless surge of the half-baked, half-witted and half-understood, as Rooney found herself twanged back and forth between heroism and hypocrisy.

The hollering went on for days, opinion columnists opinion columned, the respective Twitter trenches gained not an inch of territory and when the hullabaloo finally receded Rooney’s stance remained unchanged.

Turning down a translation offer is something she is perfectly entitled to do. While the sale of translation rights can be a lucrative business for an author, many decline such approaches for a range of reasons, from a reluctance to sanction something bearing their name in a language they don’t understand to their stance on a political issue.

On the Israel/Palestine question, Rooney is far from the first to make a stand. Iain Banks, China Miéville and Kamila Shamsie are three other high-profile names to have previously ruled out signing contracts with Israeli publishers for Hebrew editions of their work.

None have received the level of scrutiny Rooney has endured, although Shamsie had a German literary award withdrawn in 2019 when the organisers learned of her support for the BDS campaign.

“I would be very happy to be published in Hebrew, but I don’t know of any (fiction) publisher of Hebrew who is not Israeli, and I understand that there is no Israeli publisher who is completely unentangled from the state,” Shamsie said in 2018.

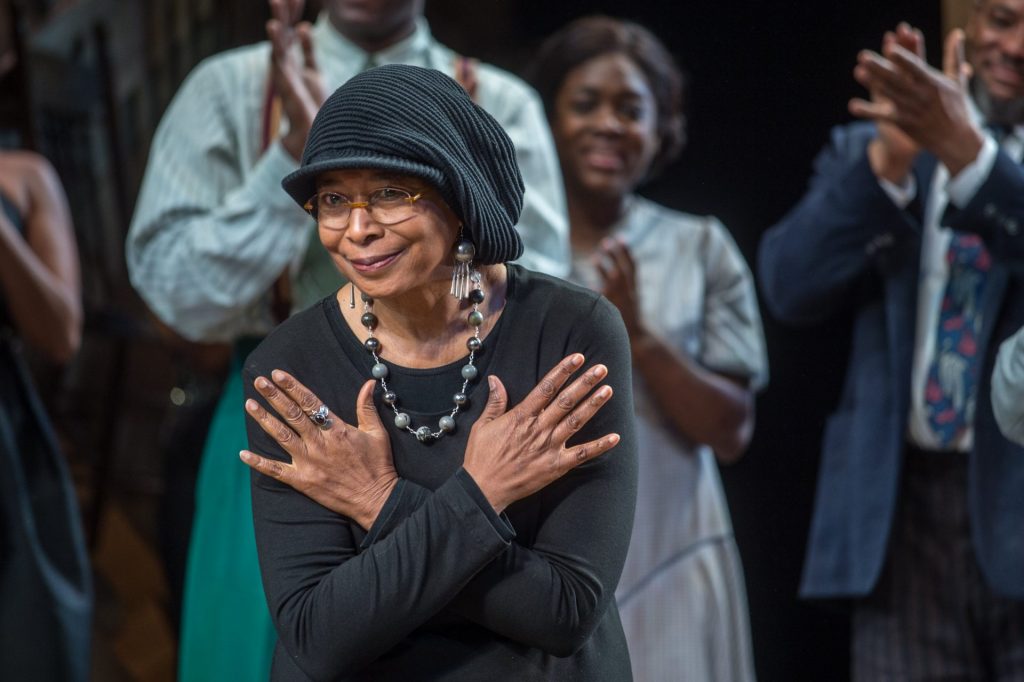

In 2012 Alice Walker refused an offer from Israel for a Hebrew version of The Color Purple. Like Rooney, Walker had been published there before but having since been part of a panel of jurors at a tribunal in South Africa discussing the Palestine situation, decided that she couldn’t approve a new edition.

She has since become a high profile supporter of BDS – but also a controversial one, with Jewish groups accusing her of promoting anti-Semitic conspiracy theories through her enthusiasm for the work of David Icke.

To its critics, BDS itself is inherently anti-Semitic, in its singling out the world’s only Jewish state. The comparison with apartheid South Africa is, they say, a smear tactic.

So if literary translation is going to become the focus of global controversy, this is perhaps the most likely place for it. As an area where authors have a significant amount of control over their work, it can be used as a simple and effective method of exercising authorial principle. That’s not to say refusing a translation contract is necessarily an easy decision, the authors mentioned will all have considered how they were disappointing Israeli readers who might well agree with them on the Palestinian issue, but what other power do they have to register their disapproval of a state whose actions they deplore?

Such gestures have a long history. Music was the highest profile branch of the arts to promote a cultural boycott of apartheid-era South Africa but writers were willing participants too. As far back as 1963 authors and playwrights including Graham Greene, Muriel Spark, Samuel Beckett, Daphne Du Maurier, Shelagh Delaney, Arthur Miller, John Osborne, Harold Pinter, J.B. Priestley, Iris Murdoch and Tennessee Williams signed an open letter withdrawing permission for their works to be published and performed in South Africa as long as racial segregation was in place.

Their action became part of a snowballing global anti-apartheid movement focused on boycotts and sanctions that helped to bring about the end of the apartheid regime.

The Cold War was a little more complicated, its binary clash of ideologies meaning authors desperate to see their work published on the other side of the Iron Curtain were prevented by the blanket bans or heavy censorship of oppressive states, while writers in the East found it almost impossible for work to even reach the West, let alone be published here.

Sándor Márai is now deservedly regarded as one of the greatest writers ever to come out of Hungary, but that recognition is entirely posthumous. When he killed himself in the US in February 1989 at the age of 88 it was just months before the end of communist rule in the home land from which he had been forced by its arrival 40 years earlier.

Convinced that language is the beating heart of a nation, he refused to allow his work, including his classic 1942 novel Embers, to be published in Hungarian while a Soviet presence remained in the country. His stance all but guaranteed him a life of financial struggle and literary obscurity but since the early 1990s his books have been published worldwide in many languages to wide acclaim – including in Hungary.

Márai’s belief that a language is the most integral part of nationhood encapsulates why something as apparently uncontroversial as translating a novel can be a powerful way of demonstrating a writer’s allegiance to a particular cause, particularly one where human rights are involved.

The Chinese novelist Yiyun Li left his home for the US in 1996 at the age of 24 and went on to become one of Granta’s 21 Best of Young American Novelists, winning a string of awards for her novels and short stories which have been translated into a range of languages. Yet one notable absence from her foreign language editions is Mandarin, something she refuses to countenance despite it being her primary tongue.

“My abandonment of my first language is so deeply personal that I resist any interpretation,” she wrote in her 2017 memoir Dear Friend, the link between language and nation so strong that she actively tried to drive Mandarin from her own subconscious until there is regime change in China.

Similarly the global best-selling Nigerian author Chinua Achebe, author of the classic Things Fall Apart, resisted for many years having his work published in Igbo, the language he grew up speaking, because he considered it to be an imperialised hotchpotch of authentic dialects.

“There is a problem with the Igbo language,” he told the Paris Review in 1994. “It suffers from a very serious inheritance which it received at the beginning of this century from the Anglican mission. They sent out a missionary by the name of Dennis. He was a scholar. He had this notion that the Igbo language – which had very many different dialects – should somehow manufacture a uniform dialect that would be used in writing to avoid all these different dialects. Because the missionaries were powerful, what they wanted to do, they did.”

For her critics, Rooney’s rejection of an Israeli-produced edition of her latest work is an empty gesture by comparison, even a narcissistic one (albeit her announcement was made to correct reports emanating from Israel that she had refused to countenance any kind of Hebrew translation). Her earlier book Normal People has so far been translated into 46 languages so she’s not making a significant personal sacrifice beyond a “no thank you” reply to her agent’s e-mail informing her of Modan’s interest.

Yet those few strokes on a keyboard still represented a political act that earned her supporters and critics with equally fervent views on a deeply controversial subject.

In the wings are those who bleat that literature and politics should be kept separate. With the 300th anniversary of Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal approaching, it’s clear that particular argument ran out of steam a very long time ago. This latest brouhaha takes one step further, emphasising the power not just of the written word but of language itself.

A European Library

A weekly selection of fiction and non-fiction, new and old, to build a comprehensive literary portrait of our continent.

THE IMMORTALS: THE SEASON MY MILAN TEAM REINVENTED FOOTBALL by Arrigo Sacchi with Luigi Garlando, trans. Mark Palmer (Back Page Press, £9.99).

There have been few European club sides to match Arrigo Sacchi’s AC Milan team that won the 1989 European Cup with a 4-0 demolition of Steaua Bucharest. Football itself was on the crest of a new era and a team featuring the brilliant Dutch trio of Marco van Basten, Ruud Gullit and Frank Rijkaard was at the vanguard of that, playing thrilling attacking football. This is the story of a team that transformed the game in Europe in the words of the man who built it, Arrigo Sacchi himself.