Luigia Vanzetti did not ask for any of this. Two months earlier she had barely

set foot outside her home village in the north-west of Italy, but here she was,

in October 1927, having crossed the Atlantic for the second time, watching

the lights of Cherbourg draw closer, their reflections making crazy patterns on water as dark as the night.

She’d made the journey to America alone; on this return voyage she was alone in the conventional sense but below deck were two urns, the cremated remains of her brother and his friend who for the last seven years had been the focus of enough global attention to ensure their names would be bound together forever.

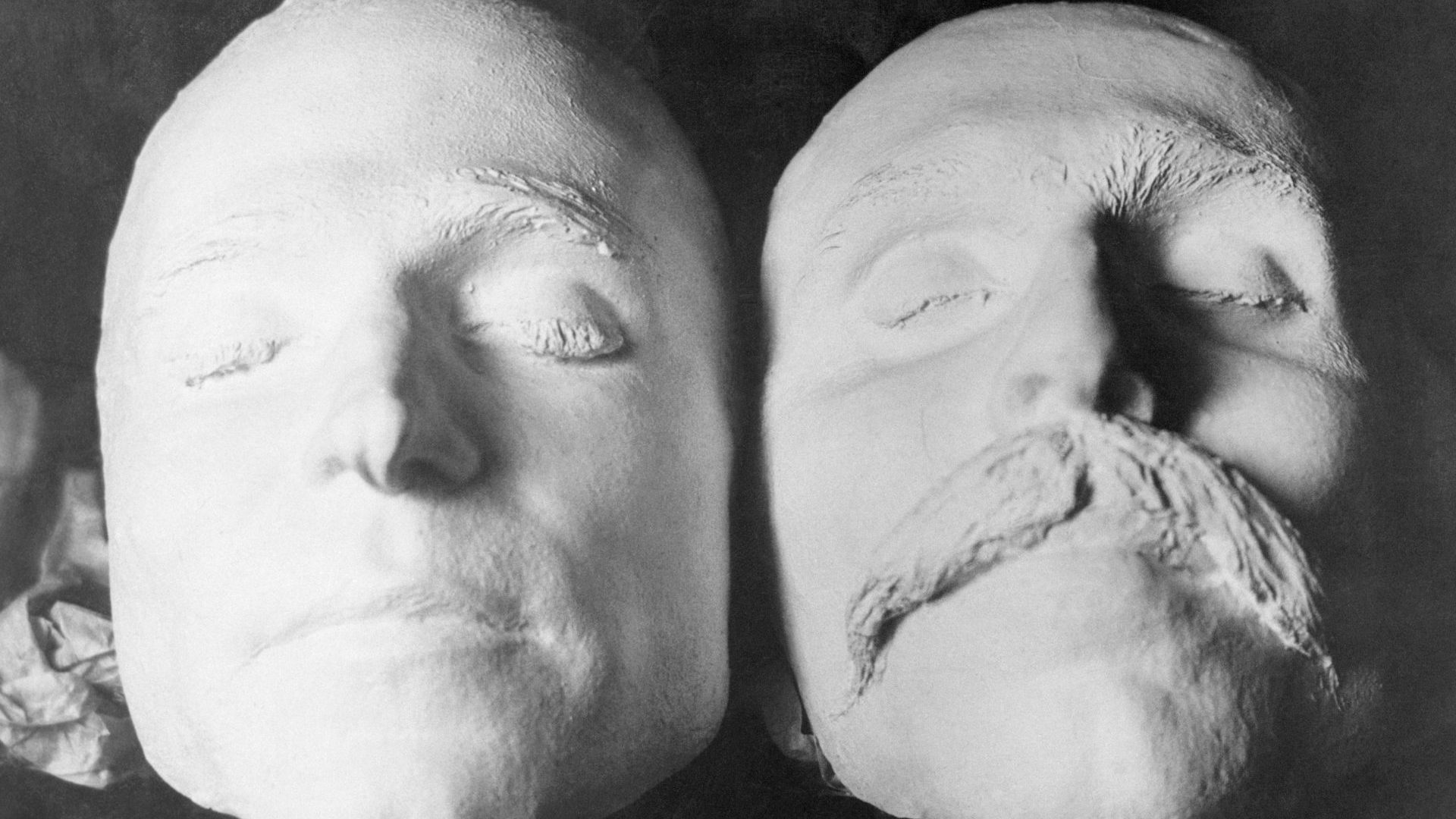

There was no Nicola Sacco any more and no Bartolomeo Vanzetti; since the dawn of the decade they’d been the single entity Sacco and Vanzetti. Individually their fates were an immeasurable tragedy for two families, together they were a cause. Even their ashes had been mixed together before

being placed in the urns.

Neither of them had wanted any of this. Luigia, certainly, as she prepared

for a journey across Europe as far south as the heel of Italy, did not ask for any of this.

A few facts were incontrovertible. A little after three in the afternoon of April 15, 1920, Fred Parmenter, veteran bookkeeper at the Slater-Morrill shoe

factory in Braintree, Massachusetts, and security guard Alessandro Berardelli left the company offices with two steel boxes containing a combined $27,000, the weekly payroll, walking the short distance along Pearl Street to the factory itself.

With the factory entrance a matter of yards away, two men on the street pulled out revolvers and shots rang out. The burly Berardelli, shot four times, was killed almost instantly. Parmenter was wounded in the chest but as he ran towards a ditch where a road gang watched dumbfounded, he was felled by a bullet to the back and died in hospital the next morning.

A car slewed around the corner at speed, picked up the gunmen, the cash

boxes and an accomplice standing guard on the other side of the street and sped off, firing at the factory and at terrified bystanders as they went.

Two days later local police called at the house of an Italian anarchist named Ferruccio Coacci who had failed to turn up when due to be deported on the day of the robbery. Coacci wasn’t there, but another anarchist, Mario Buda, was. Knowing the killers were Italian, police chief Michael Stewart suspected the house and its various occupants were behind the robbery and Buda’s car, being repaired at a local garage, was the second getaway vehicle.

As requested, the garage owner called the police when four men came to collect the car. They left without it on learning the licence plate had expired, two on a motorcycle, the others by streetcar on which they were later arrested.

Their names were Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti.

Sacco was 29 years old, an edge trimmer at a shoe factory in Stoughton, Massachusetts, a skilled job paying enough for the house where he lived with his wife and young son, growing flowers and vegetables in the garden. He’d been in the US for 12 years since leaving his home village of Torremaggiore, in the far south-east of Italy, to seek his fortune in America.

Three years older than Sacco, Vanzetti hailed from the other end of the country, Villafalletto, a village south-west of Turin close to the border

with France. He’d apprenticed to a baker and worked for a while in a sweet factory, but when his mother died in 1908, like Sacco he saw nothing left for him in Italy and boarded the liner La Provence at Le Havre, destined for New York. He worked wherever he could, in stone quarries and brick yards, on railroads and highways, until he arrived in Plymouth, Massachusetts, and set himself up as a mobile fishmonger making the rounds of the ever-growing Italian neighbourhoods.

What brought these two men from opposite ends of Italy together was the idea of revolution. They’d witnessed and experienced the injustices of rampant capitalism and xenophobia in America and, after Sacco and his wife Rosina had organised strike funds while Vanzetti was a leading light in a

1916 strike at a Plymouth cordage factory, both came to see anarchism as the answer.

They met in 1917 at a conclave of anarchists in Boston organised by Luigi Galleani, an advocate of violent revolution. With Europe in the grip of revolutionary fervour many immigrant Galleanists were keen to return to help the cause, but when the US joined the war travel to Europe became

prohibitive and in June, Sacco, Vanzetti and 60 like-minded men decamped to Mexico to await the revolutionary call. It never came, and returning four

months later they found the US in the grip of a “red scare” and their names on lists of those earmarked for deportation as dangerous foreign radicals.

By April 1920 official scrutiny had become more intense than ever, prompting Sacco and Vanzetti to devise a road trip warning comrades across

Massachusetts to dispose of incriminating literature. They needed a car. Buda’s had just been repaired. They accompanied him and a colleague to the garage, then boarded a streetcar.

A combination of their carrying pistols and some evasive answers to police questioning convinced Chief Stewart he had the men behind not just the Braintree murders but also an earlier failed payroll heist at another shoe factory. In broken English, Sacco said he’d been in Boston on April 15 applying for a passport at the Italian consulate. Vanzetti claimed he was

working in Plymouth making his usual rounds. Both men denied involvement. Both men were charged with robbery and murder.

After a heated trial and despite the prosecution case having many inconsistencies, not to mention an openly hostile judge, on January 21, 1921, the jury found Sacco and Vanzetti guilty by a 10-2 verdict. Their death sentences were inevitable.

A lengthy, unsuccessful appeals process followed, during which Sacco and Vanzetti saw their cause taken up all over the world. Nearly half a million people signed a petition demanding pardons. National and international figures voiced their support: Dorothy Parker, George Bernard Shaw, Edna St

Vincent Millay, HG Wells, Albert Einstein. None of it worked.

When news broke of their executions, to which both went calmly but still protesting their innocence, riots broke out across America while US embassies around the world were assailed by angry crowds.

And then, barely two months later, there was just Luigia Vanzetti standing

alone in the night at the rail of a ship, looking south towards the earth that

made her to which she was returning two men who hadn’t asked for any of

this, just as she hadn’t asked for any of this.

The lights drew closer but the darkness still pressed heavily upon her.