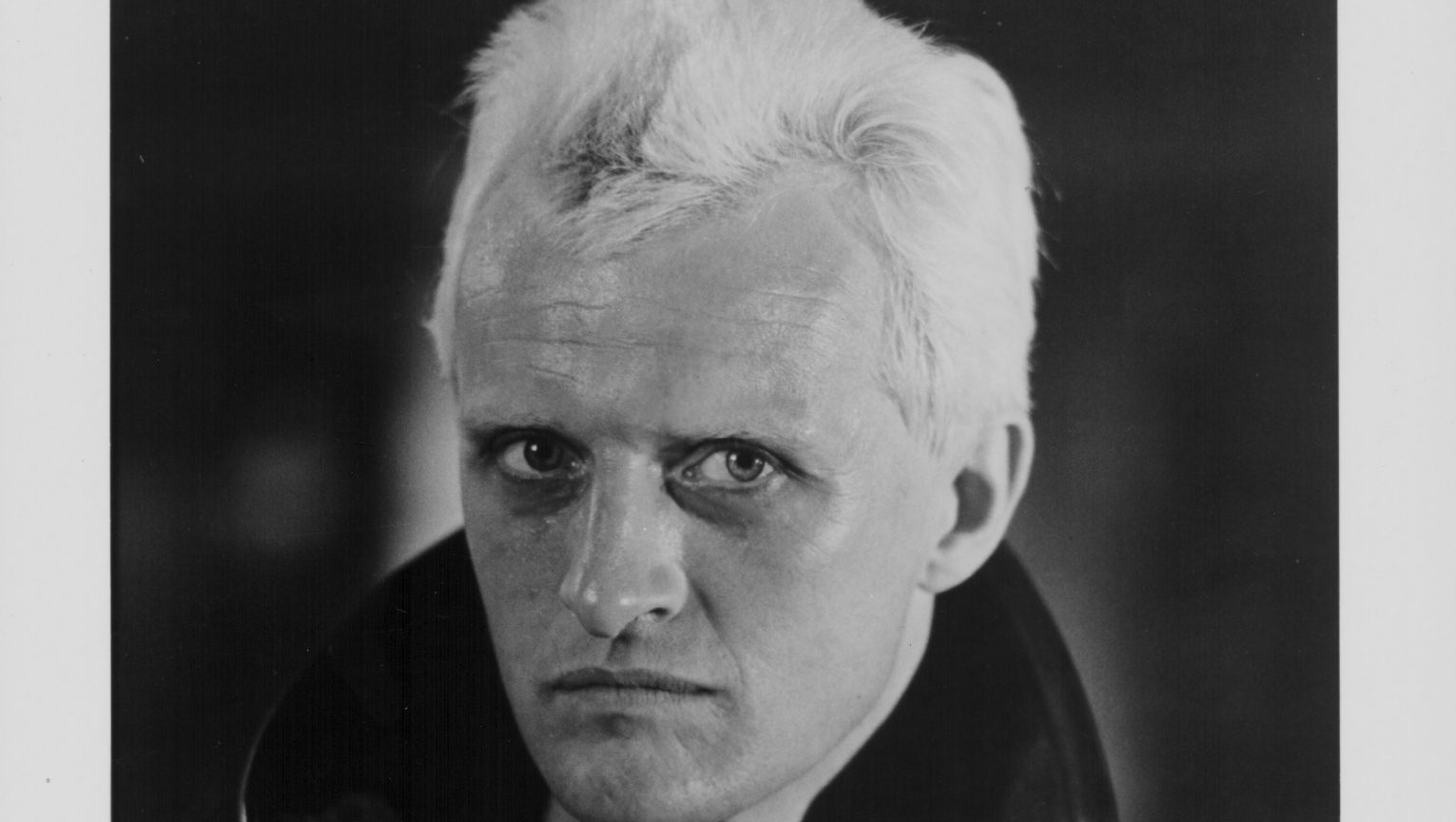

Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner baffled critics and audiences alike when it was released during the summer of 1982, flopping at the box office and only later gaining first cult status and then the wider recognition it enjoys today. The film depicted the Los Angeles of the future, a grimy gaggle of skyscrapers and neon beneath a permanently dark sky and a constant drizzle of acid rain where a renegade band of replicants – android slaves used on distant colony planets only indistinguishable from humans through batteries that last barely four years before shutting down – have arrived seeking to persuade their creator to extend their lifespans. They are hunted by Harrison Ford’s Rick Deckard, an off-the-peg film-noir gumshoe, and led by Nexus-6 replicant Roy Batty, played by Rutger Hauer.

Batty could have been a conventional two-dimensional figure, the vengeful, ruthless robot, short on nuance and long on clichéd dialogue, but Hauer gave him not just a soul but the soul of a poet. This man-machine was cramming a human lifetime’s worth of existential angst into his four-year span, ranging from childlike wonder at a giant teddy bear early in the film to crushing the skull of the replicants’ creator with his bare hands when he couldn’t lengthen his battery life.

Hauer’s performance, largely responsible for the film’s classy reputation today, truly shone in Batty’s final moments. At the conclusion of a thrilling chase through a dystopian landscape, against all expectations Batty saves Deckard’s life. Tossing him to one side and facing his own imminent mortality, the android produces one of the great moments in modern cinema.

The last days of filming on Blade Runner had been frantic and exhausting due to a threatened Actors’ Guild strike. When the time came to shoot Batty’s demise everyone had been on set for 25 hours straight. Hauer announced he could not continue. That evening, exhausted to the point of delirium, he went through his character’s scripted final monologue and realised it was far too long; too “operatic” as he described it. He crossed out all but two lines,

appended one of his own and fell asleep.

When filming recommenced the next day a rapidly declining Batty sat opposite Ford’s bewildered Deckard and delivered his dying speech, the lines Hauer had cut and amended the previous night and for which he remains best known today.

“I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe,” he said. “Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time. Like tears in rain.”

Blade Runner was ahead of its time. The global success of E.T., released the same summer, illustrated how cinema audiences liked their science fiction in 1982. Among the lukewarm reviews for Scott’s film, however, Hauer’s

performance drew consistent praise. Not that the Dutch actor, still new to Hollywood, was overly concerned about critical approval, or indeed forging a career in California.

“One of the things I have never been able to do is lick arse in Los Angeles,” he said, going on to dismiss Hollywood as “a bunch of producers and distribution people who decide together with some agents what material is going to go. If you happen to be in it then your face is nailed to one character all over the world and they cannot see you in any other way”.

Batty was only Hauer’s second major Hollywood role. The previous year he’d

appeared opposite Sylvester Stallone in the cat-and-mouse thriller Nighthawks as a charismatic German terrorist named Wulfgar. Despite repeated on-set clashes with Stallone and the deaths of his mother and his best friend in the Netherlands while he was filming in New York, Hauer rated Wulfgar as one of his best performances.

Despite Wulfgar being conceived as a murderous psychopath killing for fun,

Hauer added a sprinkling of depth to the role, even reciting poetry by Heinrich Heine during his death scene. “Bad guys don’t have tails and a

pitchfork,” Hauer wrote in his 2007 autobiography. “They can be charming. They can be sharp and businesslike.”

Hauer brought pioneering nuance to Hollywood when burly Europeans in

Hollywood could expect little more from roles than grunting henchmen, murderous Nazis or ring fodder for Rocky Balboa. Of his terrifying role in

the 1986 thriller The Hitcher, blamed for prompting a sharp decline in

American hitchhiking, he said, “I think in my darker characters I go a little

further than most American actors. Maybe it’s because I’m not afraid of that

side of myself.”

His long run as the face of Guinness’s ‘Pure Genius’ advertising campaign of

the late 1980s and early 1990s set up Hauer financially for life, meaning that he didn’t have to play the Hollywood game. While he would stay in Los Angeles for extended periods he was always drawn back to his native land. The Netherlands remained his home.

“Being brought up in Holland, a small country, makes you seek adventure,” he said, and this Dutchness was a key influence on his personality and career.

Hauer was born in Breukelen to actor parents who ran an Amsterdam drama

school, in a household where “it sometimes seemed to my three sisters and me that the arts were more important than we were”. The only aspect of family life on which he looked back fondly were childhood holidays to the island of Schiermonnikoog in the West Frisian Islands. The vast skies and wide, flat sandy beaches allowed a glimpse of the infinite, a horizon that promised mysteries and adventure, all with a sense of rootedness in the landscape.

“It was, and remains, an ideal, innocent place,” he wrote of his endless

childhood summers there.

Tantalised by that horizon, Hauer ran away to sea at 15 then dabbled in work as an electrician and joiner before half-heartedly applying to drama school in his late teens. Expelled for missing classes, he joined the Dutch army but was kicked out for being ‘psychologically unfit’ after refusing to train with deadly weapons. For all his screen action roles, Hauer detested violence, something he attributed to a collective Dutch folk memory of the German occupation into which he was born.

Having returned to drama school, he shot to fame in the Netherlands in 1969

thanks to Floris, a swashbuckling medieval drama series directed by a young Paul Verhoeven, who went on to cast Hauer in five of his films including 1977’s second world war drama Soldier of Orange, an early cable TV and video

success that led to Hauer’s courting by Hollywood and a subsequent global

fame negotiated and played out entirely on his own terms.

“That young boy who sailed the seas is still here with me,” he said just four

months before he died, “and he’s saying this about my life: ‘that was awesome.’”