There are two main tragic aspects to Russia’s war in Ukraine. The first one is immeasurably bigger, and it is all the horrors of real war: dead people, ruined cities and villages, desperate refugees, lying generals, incompetent politicians… Luckily we have somewhat fewer of the latter in this particular war, and I’m unexpectedly impressed by the performance of some of the world leaders, let alone Ukraine’s brave president, Volodymyr Zelensky. I’m also overwhelmed by the display of global solidarity with the people of Ukraine, the incredible charity and goodwill from ordinary citizens everywhere in the world.

But I’d like to focus on another tragic aspect, barely visible outside Russia. Judging by not only opinion polls – which are usually doubtful, as they’re conducted by official institutions – but by friends’ reports from Russia and personal observations, the majority of Russians support the invasion and see it as a matter of national pride, not national shame.

None of my Facebook friends nor Twitter connections cheer for Russian aggression and love Putin, but they are all complaining that most of the people they meet are happy about the invasion and sound absolutely brainwashed. Needless to say, they are shocked and scared.

Me too: I’ve underestimated the manic ways of Putin and his determination to destroy Ukraine, not believing he would go far beyond his usual hybrid war tactics. Now, it looks as if I have also overestimated the protest potential of the Russian people.

Why is this so? Some answers are obvious. Not just political opposition, but civil society as well, has been effectively cut down in the past couple of years. The protest leader and main conductor, charismatic Alexei Navalny, was unsuccessfully poisoned and later successfully jailed. All his team, which had a network in almost every Russian city and region, has been either put in prison or squeezed out of the country.

Very logically, after cracking down on political and civil activists, the authorities and police came after independent journalists and bloggers. All unwanted media units, mostly online ones, have been shut down. Until very recently, only three of those remained: one newspaper, Novaya Gazeta; one radio station, Echo of Moscow; and one TV channel, TV Dozhd. In the past week, two of those have been closed down. Only Novaya Gazeta, led by last year’s Nobel prize winner, Dmitriy Muratov, survives.

At the same time, the Kremlin propaganda was working very hard. I thought Russian – actually, ex-Soviet! – people had developed strong immunity against state propaganda, but now we see that evil TV radiation still works on some levels. Contentwise, the narrative goes along chauvinistic lines: Ukrainians are Nazis oppressing and killing Russian nationals and we are there to save them from genocide; the US and Nato are the real masters of Kyiv’s puppet regime, aiming at destroying the great Russian state, the world’s stronghold of traditional values and orthodoxy.

Nothing new, except maybe for the term “Anglo-Saxons”, used to divide the weak but relatively sane Germans, French and Italians from the totally monstrous Britons and Americans. Another new feature is the sheer intensity of military hysteria – on state-owned and affiliated channels they have replaced all entertainment programming with patriotic talk shows and fake newscasts.

Another reason for the muted reaction is that unlike in the UK or US, there’s no strong tradition of anti-war campaigning in Russia. There were no protests against war in Afghanistan until the late 1980s, very little opposition to war in Chechnya and literally no reaction to the invasion of Georgia in 2008. The most extreme example is the 2014 annexation of Crimea and invasion of Donbas, which was overwhelmingly cheered by the population and formed the infamous “Crimean consensus” between bellicose Putin and the happy nation.

Just a little illustration from my professional field: Russian rock music, famous for its political and social content, has produced almost no pacifist songs until very recently.

There is no leadership in the civil society camp, and lots of people are simply frightened by oppression. Nevertheless, there are anti-war protests in dozens of Russian cities, and I see them as acts of pure heroism.

Sadly, the data shows that most Russians are either supportive or indifferent to developments.

Traditionally, Putin and his revanchist agenda are cheered by elderly people, ever nostalgic for the USSR and imperial might.

Middle-aged men also form a large body of pro-regime supporters, mostly working-class but also middle-class, the so-called “muzhiki” – violently homophobic, latently misogynistic, antisemitic, xenophobic and fond of “traditional values”, of which alcohol is the crucial one.

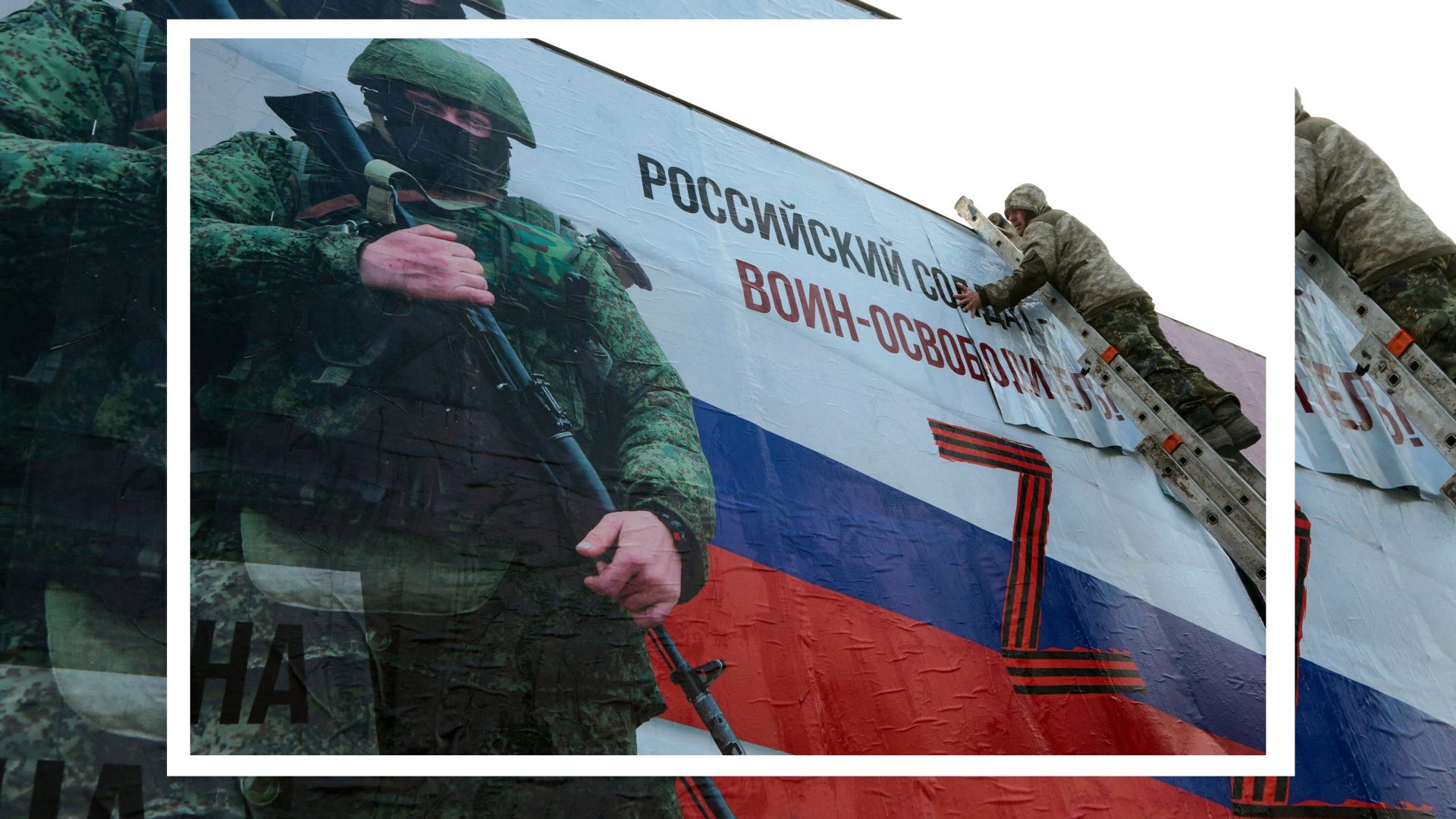

One worrying development is the support of provincial youth, such as the young gymnast Ivan Kuliak who attached the pro-war “Z” sign to his leotard recently. Unlike the welleducated, cosmopolitan and pacifist youngsters of Moscow and St Petersburg, they seem to believe Putin’s militaristic hype. And it’s they who fill the cannon fodder conveyor…

Eventually (if not already) Russia will become a bona fide pariah state with zero sympathy and trust from the rest of the world. The regime will be unanimously labelled as totalitarian and fascist, and world democracies (if they remain, which I think is highly likely) will cut all ties with it.

Will isolation, boredom and poverty cure Russia’s imperial blues? I’m not sure. I’m afraid that with or without Putin, this country won’t change much and, unlike the Germans in the 1940s, I don’t believe Russians will seriously repent and start “de-Putinisation” of the state.

Eventually, the paranoid pseudoempire will simply fall apart. I hope the future will prove me fundamentally wrong.

Artemy Troitsky is a Russian journalist, music critic, concert promoter, radio host and academic who has lectured on music journalism at Moscow State University