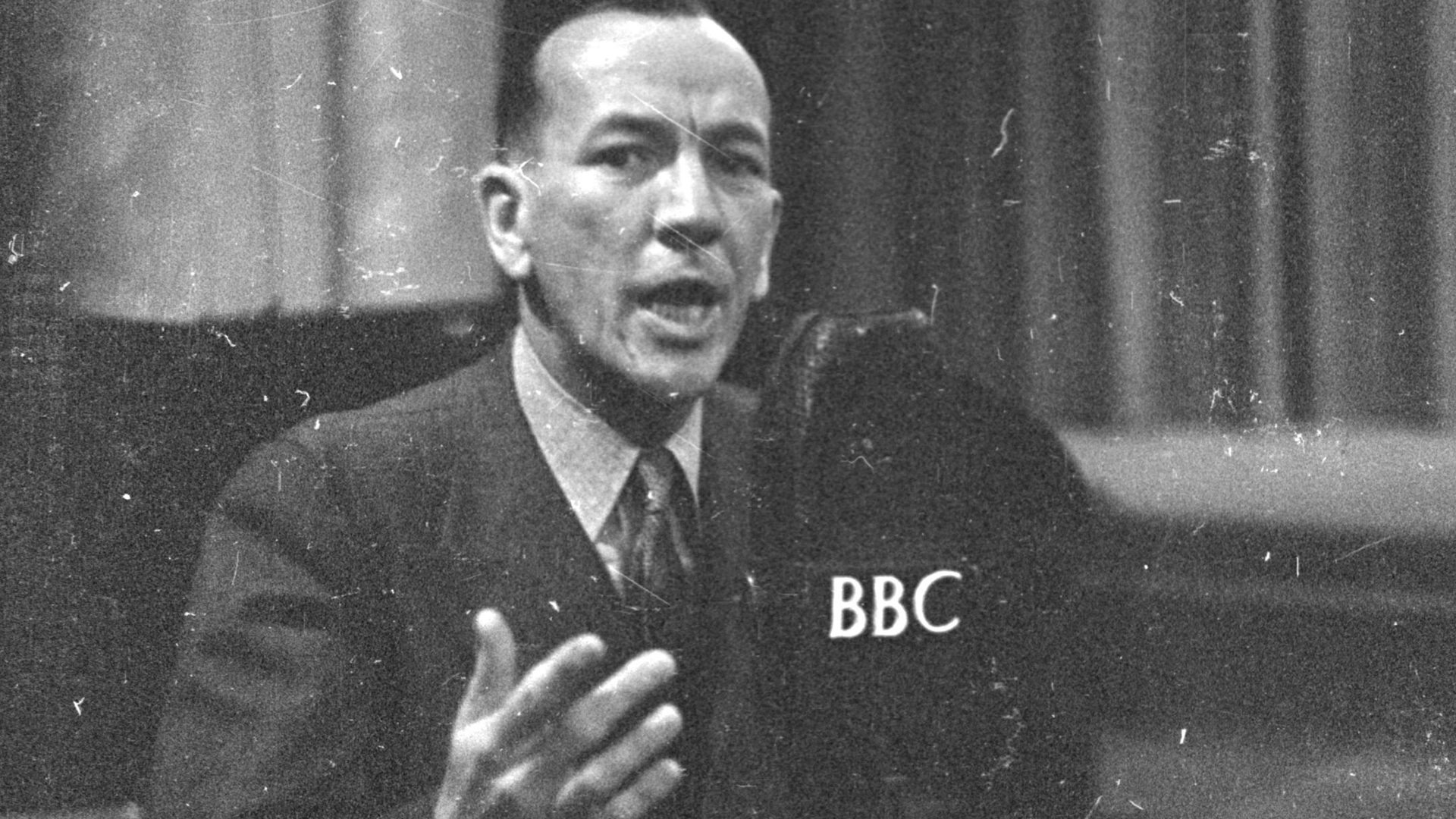

“Ordinary people like you and me know something better than all the fussy old politicians put together,” says the protagonist of Noel Coward’s 1939 play This Happy Breed. “We know what we belong to, where we come from, and where we’re going. We may not know it with our brains, but we know it with our roots.”

Written on the eve of the second world war, it contains a theatrical premonition of Britain’s “finest hour”. In the final scene, the hero – a veteran of the first world war – tells his grandson: “We ’aven’t lived and died and struggled all these hundreds of years to get decency and justice and freedom for ourselves without being prepared to fight 50 wars if need be – to keep ’em.”

Whenever I want to find true north in the moral compass of this country’s history, I re-read that speech. And then compare it with what’s on the news.

As we approach a bleak midwinter, in the year the Tory Party gave us three prime ministers, Matt Hancock in the jungle, the Rwanda deportation scheme and the Michelle Mone scandal, this is very much not our finest hour.

To adapt Coward’s phrase: we don’t know what we belong to; we don’t agree on where we come from; and we have no clue as to where we’re going.

We’re not alone in this, of course. Free-market economics, illegal wars, austerity and networked disinformation have combined into a caustic substance to corrode many western democracies. But we’ve got a bad case of it.

The rot starts at the top: the royal family is riven with intrigue and suspicion because Harry and Meghan wanted to live a non-ceremonial lifestyle free of pressure and racism.

The spectacle is both tawdry and momentous – Harry’s break from the royal family is just as serious a political crisis as Edward VIII’s abdication in 1936. But this time the roles are reversed – it’s the good guy who’s been kicked out.

Westminster, meanwhile, is riddled with legalised corruption. The VIP lane for PPE suppliers, the illegal lockdown parties, Boris Johnson’s attempt to lie his way out of the Chris Pincher scandal… these are just the lowlights of a year that has kept on giving until the end.

But there’s something more insidious going on. In the Cameron-Miliband era we used to say politics was technocratic. Now it’s the opposite: politics is all emotion and no competence.

The Manston camp was filled to overflowing with sick and desperate refugees simply because ministers did nothing, out of spite. And when the ministers were found out, the asylum seekers were simply driven to Oxford Circus in London and dumped. Nobody will lose their job, or be pilloried in the tabloids for overseeing that.

When you appoint a cabinet of bullies, and switch prime ministers so often that patronage – not competence – becomes the main criterion for selecting teams, you erode the culture of challenge in the civil service. Dominic Cummings may be long gone, but the after-effects of his assault on Whitehall reverberate across the departments, anecdotally paralysing the machinery of government.

And what of the people? Ngozi Fulani founded a charity to help black survivors of domestic abuse. She was treated in a racist way by a revered palace official, who was then sacked. Ms Fulani then received a hail of online racist abuse – for her name, her looks, her temerity in complaining.

We’ve become spectators in a theatre of cruelty where racism is the underlying ethos: the Manston migrants, Meghan, Ms Fulani are all seen as legitimate targets because in the tabloid/shock-radio culture – which only reflects and reinforces what is said in pubs – they are the automatic “other”.

How we achieved this spectacular disunity, this tolerance for incompetence and racism will be clear to historians. Three decades of freemarket economics gave the home-owning, pension-earning part of the population a stake in the exploitation of those obliged to rent and pay off their student loans.

Then a decade of austerity eroded public services to the point where people sit indignantly on the hard chairs at A&E loudly questioning whether those in beside them should really be there.

Then they sold us Brexit as the cure for everything. And then the cure didn’t work.

If this were happening amid global peace and harmony, it might be containable. But our habitual anger, the casual way in which we stoke existential divisions are a symptom of the wider global breakdown.

The one point of light this year for me has been the way in which Britain proactively supported, armed and aided Ukraine. I don’t even begrudge Boris Johnson his grandstanding trips to Kyiv: if this was the price we paid to put a thousand anti-tank missiles into the hands of Ukraine’s soldiers, it was worth paying.

But let’s see whether solidarity with Ukraine lasts until the end of a winter of potential power blackouts, freezing homes and overwhelmed food banks.

For Vladimir Putin also watches the telly. He understands the difference between the Britain of Noel Coward and the Britain of Matt Hancock.

In 2022, Russia and China combined to declare themselves our cultural and geopolitical adversaries. They understand our weaknesses better than we do.

They believe our democratic society is doomed, and the only way to achieve the national self-belief evidenced in Coward’s 1939 play is through dictatorship. Maybe in 2023 we can prove them wrong – but it will take an effort that many people in business and public life seem not to possess.