The Scream is the one the world knows; the agonised face caught beneath a raging orange sky. Its infinite howl affirms our view of Edvard Munch (1863-1944) as an artist wrecked by mental torment, the man who wrote in an undated notebook that “sickness, insanity and death were the black angels that guarded my cradle and have since followed me throughout my life”.

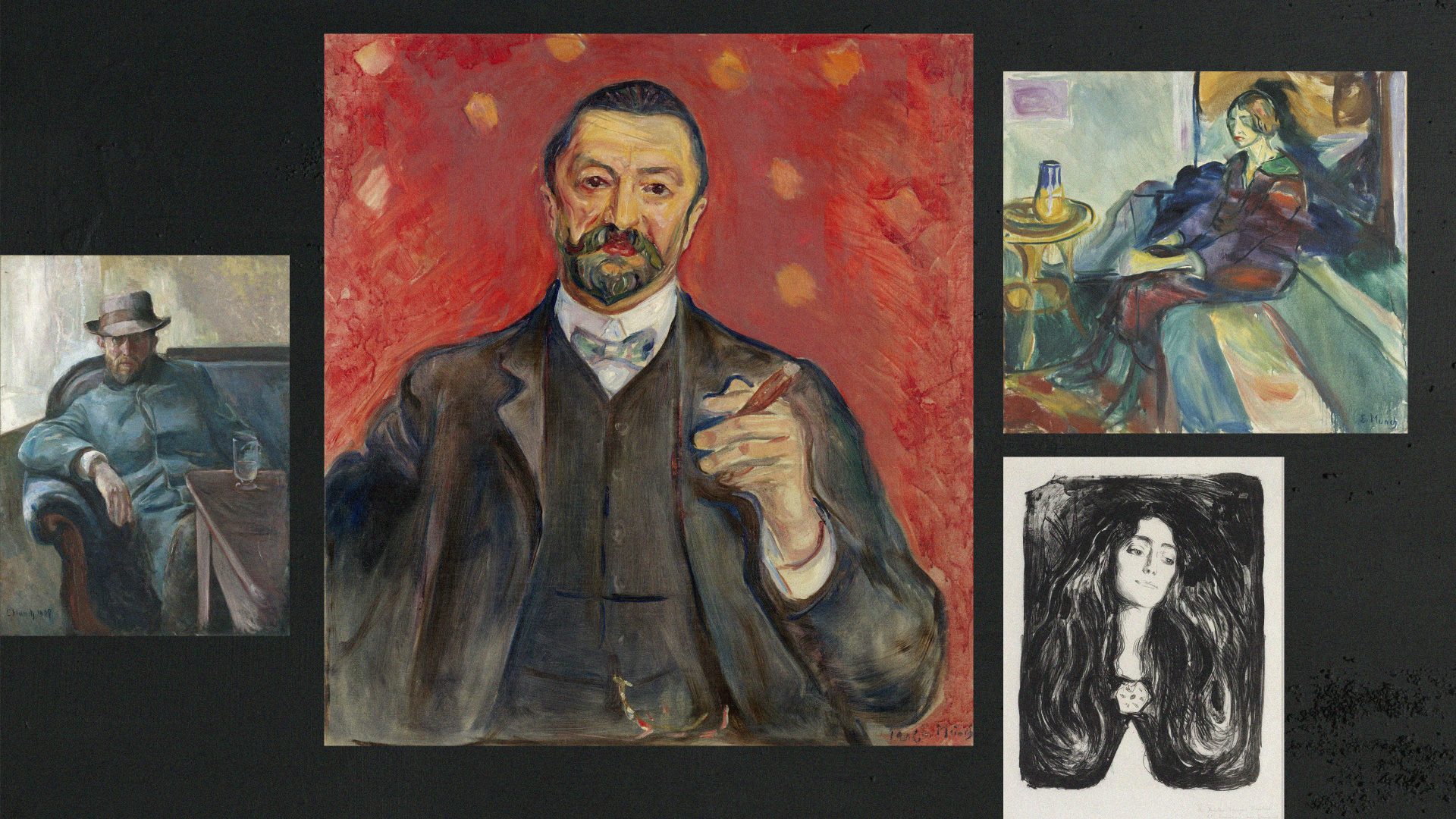

But there is more to Munch than one painting, or the narrative of a loner beset by his own demons. He was prolific, successful and supported by a network of family and friends. Many of this network feature in the more than 400 portraits he created during a six-decade career. They form the basis of an impressive exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery.

Munch’s family tree is filled with creative relatives who were painters, writers and poets. Each had an influence on his art and life. The paternal side of his family included the neo-classical painter Jacob Munch, who co-founded the Royal Drawing School in Kristiania (Oslo); Peter Andreas Munch, Edvard’s uncle, was a respected scholar who wrote the classic History of the Norwegian People.

The painters Frits Thaulow, Edvard Diriks and Ludvig Ravensberg (1871-1958) were all related to Munch. In Kristiania, the family of his mother, Laura Bjølstad, were seafarers with an artistic trait.

Munch had everyday contact with art through the paintings and portraits on the walls of his family home. One family heirloom was a pair of wall paintings of his great-grandparents by Peder Pedersen Aadnes. These accompanied each house move that Munch’s father, Christian, a military doctor, and his wife made. Later, Edvard would inherit the paintings and place them on the wall of his home alongside his own portraits of family and friends.

Munch was the second of five children. His older sister Johanne Sophie was born in 1862, his younger brother Peter Andreas in 1865 and younger sisters Laura Cathrine and Inger Marie born in 1867 and 1868. The latter saw their mother’s death from tuberculosis at the age of 46, when Munch was five.

The loss was traumatic. Munch’s father became a melancholic near-recluse, but living with them was Karen, their mother’s younger sister, who took over the household and the children’s welfare. Adding to their trauma, Sophie died of tuberculosis in 1877, aged 15, a harsh blow to Edvard and his siblings.

Munch’s father planned a career in engineering for Edvard, and for Peter Andreas to become a doctor, like his father, which he did. However, Edvard Munch’s focus was on graphic art and painting, and Karen, a talented artist, encouraged him to practise drawing when he was unable to attend school through illness.

In 1880, after his aunt had extracted him from technical college, a 17-year-old Munch enrolled at the Royal School of Art and Design in Kristiania under the mentorship of Christian Krohg and Felix Thaulow, leading realist painters. He wrote in his diary, “It is my decision now to become a painter.” He would win three art scholarships.

At the art school and afterwards, he mixed with a group of affluent middle-class radicals, artists, writers and political activists, nicknamed the Kristiania Bohème (Kristiania Bohemians) who met in local cafes, their debates and arguments aided by a desire for change, and alcohol. It led Munch to alcohol dependency and increased his stress, but mixing with like-minded people who believed in personal freedoms steered him to create expressive work informed by his feelings and experience. He called it “soul art”.

Another friendship group were intellectuals, affectionately referred to as The Mycenaeans. A third group encompassed all his male friends and were nicknamed The Guardians. These promoted him in published essays, wrote excellent reviews, placed his work in galleries, bought his paintings, sat for portraits, proclaimed him as a national icon, and looked after his reputation. Munch referred to them as “my soldiers, my warriors, my battalions, the Guardians of my art”.

Munch lived in Scandinavia (Norway separated from Sweden in 1905), in Paris and Berlin. He networked, creating contacts across Europe. He was an astute businessman, forming useful friendships for patronage.

At home, Munch’s life-support was his family, and loyal relationships. At times, through nervous exhaustion and alcoholism, his mental and physical strength collapsed.

In 1908, he was hospitalised in a private clinic in Copenhagen for two months, under the care of Dr Daniel Jacobsen. He had suffered a mental breakdown in Berlin, not helped by regularly drinking a bottle of port for breakfast.

On recovery, his friends encouraged him to return to Norway, to begin again. Now rarely drinking alcohol, he succeeded, becoming one of the most prolific and successful painters of his time.

During a six-decade career Munch created over 1,700 artworks. Four hundred were portraits of family, friends, lovers, patrons, collectors, artists and writers, and himself.

In an era of Jung and Freud, contemporary critics continuously searched for a psychological underbelly. In 1890, the German art critic Franz Servaes had stated: “A painter like Munch is rooted in the psychological with all his fibres. He cannot even depict a landscape without making its soul his own. For the same reasons, he is also a highly sensitive portrait painter.”

Munch’s portraits had a potency that gave insights into his relationship with the sitter. At times the sitters did not like the portraits he painted of them.

Munch’s self-portraits – there are many – were created throughout his life, depicted as himself, or staged as an alternate ego. In many he is portrayed with a palette and brushes, a traditional painter’s portrait. In another, he is dead, undergoing dissection.

Kristian Emil Schreiner, Munch’s doctor and friend, was a professor of anatomy who took him to a morgue so that Munch, at his own request, could watch a dissection. In the lithograph The Anatomist Schreiner 1 (1928-29), Munch replaces the body of an old man under dissection with a body-portrait of himself under the anatomist’s knife, on the autopsy table.

The exhibition’s curator, Dr Alison Smith, has put Munch’s mental health to one side to study his art. What shows through is the naturalness of his approach to composition and painting, each work exploring the inner psychology of the sitter.

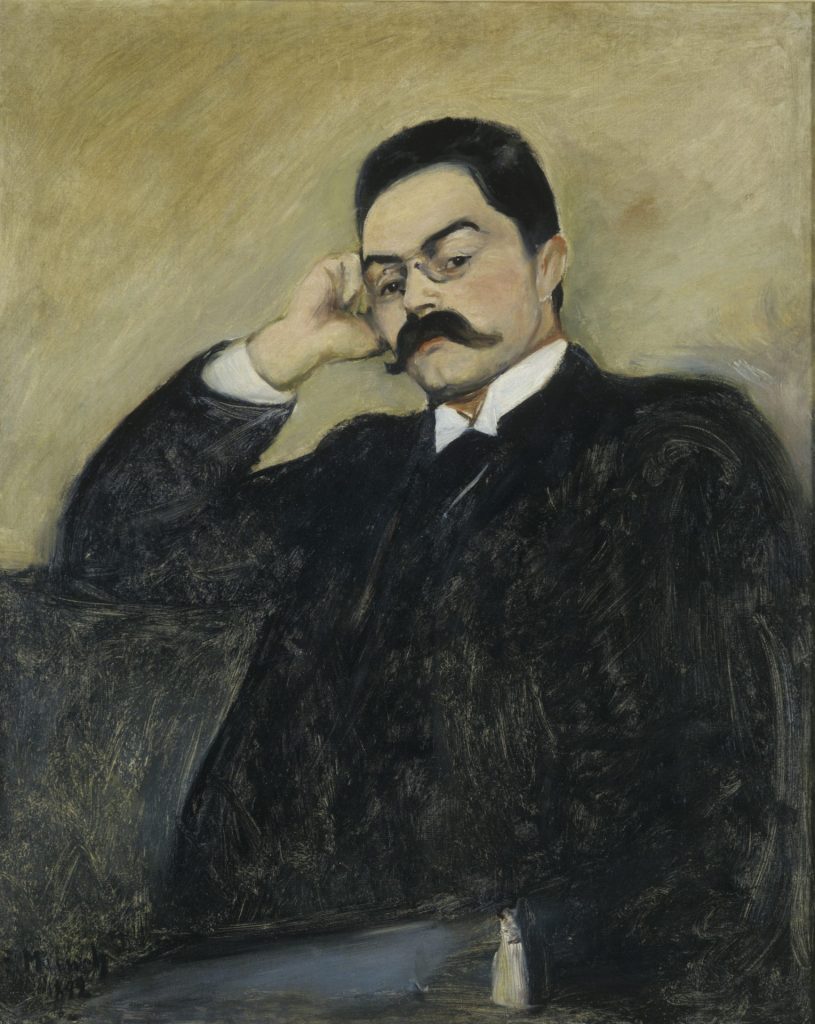

In Christian Munch with Pipe (1885), his bearded father looks down to light his pipe, in a gentle portrayal. There is a remarkable portrait of Munch’s friend, the anarchist political activist Hans Jaeger (1889), quietly seated on a sofa, his eyes fixed on Munch; and the writer Jappe Nilssen (1909), portrayed full-length in a city suit.

The lawyer Thor Lutken (1892) is seated with the sleeve of his jacket along the bottom edge doubling as a moonlit landscape with two figures, a picture within a portrait. Did it have a hidden meaning? The couple are similar to figures in an earlier painting of lovers by Munch.

The portraits of the physicist Felix Auerbach (1906), Munch’s doctor and patron, and Dr Daniel Jacobsen (1908), his doctor, all reveal their view of Munch through facial expressions. There is no repetition, each work is a stand-alone pictorial account of the sitter.

As a successful artist, Munch had several houses, and his staff were often asked to model for him. Sultan Abdul Karim was employed as a chauffeur. A half-length portrait portrays him dressed in clothes for winter temperatures with a large green scarf wrapped tightly around his neck.

Munch also dressed in a similar fashion, and this mirroring effect appears in his self-portraits. Less familiar perhaps are Munch’s visions of his workers, including Karim naked. Knowing this brings a curiosity to studying the portraits on display. Was it his analytical vision of the sitters, or the reality?

The majority of Munch’s portraits are of male friends and associates. The women were primarily family and close friends. His sister Sophie appeared posthumously in Munch’s famous work The Sick Child. Exhibited in Paris in 1886, its content caused a sensation. Munch, with his commercial eye, made further copies to sell.

Evening (1888) is a profile portrait of his sister Laura, painted by a lakeside when the family were on holiday. Laura suffered from mental illness and was sectioned for life in an asylum. She stares fixedly ahead, in isolation. In The Brooch, Eva Mudocci (1902), Munch portrayed his dear friend, the English violinist Eva Mudocci, in a sensual headshot lithograph.

Other women were not so lucky, particularly those who had encountered destructive personal relationships with him. Those he disliked could be given malicious portrayals.

During his life, many of Munch’s portraits remained with him, propped against his studio walls, as if to surround himself with friends. He died of a severe cold on January 23, 1944 at the age of 80.

His last work was inevitably a portrait lithograph of a friend – Hans Jaeger, based on the much earlier portrait of 1889. Even at the end, Edvard Munch did not scream alone.

Edvard Munch Portraits is at the National Portrait Gallery, St Martin’s Place, London until June 15