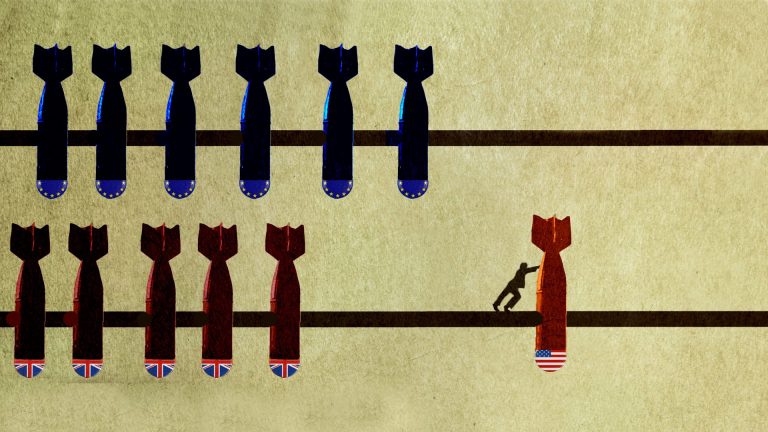

Britain cannot trade freely with Europe any more. We would like, though, to buy and sell weapons from EU countries, as well as to deter Russia from starting further wars in Europe.

Both those things depend in large part on a defence and security pact that could be announced at the Brexit reset summit on May 19. Yet there is a problem.

“The agreement is being held up over fish,” says Luigi Scazzieri, assistant director of the Centre for European Reform. “I don’t think it will be struck until fish is resolved. A positive scenario is one where both are agreed at the May summit.”

Conflicting reports about each side’s red lines and willingness to give way have been a feature of the negotiations. In mid-April, Emmanuel Macron was said to be willing to back down over demands to access British fishing waters. Most recently it is the UK who are said to be willing to give European fishers a multi-year deal and freeze current quotas.

But why would powerful nations with sophisticated economies even consider scuppering a deal over fish? Britain imports roughly twice as much fish as it exports. The industry is not nothing – it was worth £1.1bn in 2023 – but that is about 0.03% of our total economic output. Fishing is in decline, and not just because of Brexit. France is little different: fishing is worth €1.1bn there and provides 13,000 jobs.

Yet the fishing industry has a powerful hold over national imaginations that far exceeds its monetary value. It is intimately bound up with how maritime nations think about themselves and project their power beyond their borders.

Who owns the sea? Is the Gulf of Mexico really the Gulf of America, as Donald Trump believes? How far do a country’s fishers have the right to go in pursuit of their catch? Is it possible to share fishing grounds without exhausting them? These might seem arcane questions, but they played a significant part in the Brexit referendum and the torturous negotiations afterwards.

Now, with Boris Johnson’s deal up for renegotiation by June next year, they are back in play. And this is not an occasional problem. A new fishing deal now has to be thrashed out every year.

Tensions over fishing go back half a millennium. Pre-medieval Britons ate little sea fish, and most people did not know how large or extensive the seas around Britain were. For hundreds of years Norse warriors regularly crossed the North Sea to raid and pillage settlements. Britons were in no position to assert our authority over the sea.

That changed when demand for fish grew, partly because it could be eaten on the many Catholic fast days, and kings began to demand the use of fishing vessels to move soldiers. Nonetheless, England was surprisingly liberal about fishing rights, generally allowing French and Flemish boats to fish off the coast and sometimes even letting them salt or sell their catch and dry their nets. Scotland took a much less tolerant approach and fishermen there would attack Dutch herring boats that came closer than 28 miles from the shore.

Gradually, and not very effectively, English kings began to issue licences and levy fees on foreign boats that sold fish in England. Fishing started to appear in treaties. As Trump knows, taxing foreigners is generally more popular than taxing your own citizens – even if it ends up harming you.

It was not until 1577 that one man made the argument that only the English, Welsh and Irish had the right to fish off their own coasts, and were letting themselves be ripped off by foreigners. “Where now, to oure great shame and reproache, some of them do come in a manner home to our doors; and among them all, deprive us yearly of many hundred thousand pounds?” asked Dr John Dee, Elizabeth I’s court astronomer. The queen ignored him, as his proposal would have infuriated her neighbours. She believed in the principle of mare liberum – that the seas were open to all nations.

That all changed under James I. The Dutch fished freely in the North Sea, and the English began to believe that they were stealing vast quantities of herring that were rightfully theirs and selling them back at enormous profit. Obviously, the Dutch disagreed. They had a powerful advocate in Hugo Grotius, a lawyer who wrote a hugely influential book called Mare Liberum. Grotius was trying to justify the fact that the Dutch had seized a Portuguese ship in the East Indies, but Mare Liberum shaped the way European nations thought about the sea for hundreds of years. No one could own the sea, he argued, because it was a fluid thing and its resources were (so it seemed at the time) inexhaustible. Land could be transformed by human labour. The sea could not.

The fact that the ship in question was seized off the coast of Singapore, and that the King of Johor might therefore have thoughts about it, was irrelevant to Grotius. Trade was the imperative, and the sea enabled it to happen. His book was a direct challenge to Spanish and Portuguese claims to control the seas around Africa and the East Indies. That, at least, was something England could agree with him about.

Back in England, James declared that he would force all Dutch fishing boats to pay for a licence. For diplomatic reasons the threat was withdrawn, but a fierce dispute soon broke out over who had “discovered” Spitsbergen (now part of Norway) and had the right to hunt whales there.

Fish and whales were only part of the new determination to assert English dominance. Royal Navy ships became more and more diligent about enforcing an old custom – the demand that foreign ships lower (or “strike”) their flag when they saw an English ship. This is a sign of surrender at sea and was deeply resented.

Sure enough, the most influential challenge to Grotius’s argument came from an Englishman, John Selden. Mare Clausum (The Closure of the Sea) pointed out that the sea’s resources were not limitless, and the fact it was fluid did not mean no one could own it, especially if they had been exploiting it for a long time. Selden argued that England therefore had the sole right to control and fish in the sea immediately around the British Isles.

Meanwhile, English relations with the Dutch went from bad to worse. Once they had disagreed over fish. Now they were at war. By the time William of Orange successfully invaded in 1688, the Navy was in a beleaguered state. Britain was no longer in a position to assert her naval power, and in 1702 a Dutch jurist proposed that maritime dominion should extend as far as a cannon could fire from land – about three miles.

For nearly 250 years, that rule held fairly good, though it in no way confined anyone’s military ambition. Rule, Britannia!, which was written in 1740, urged Britons to “rule the waves”. The Royal Navy was able to use its global dominance to vastly expand the empire, subdue Napoleon, blockade New England and fight a war in Crimea. But the high seas remained nominally free.

That changed after the second world war. Some countries pushed their dominion out to 12 miles. Others, if they knew they would be unchallenged, went further. The US, Peru, Chile and Ecuador claimed maritime dominion as far as 200 miles from the shore.

Trying to resolve the increasing number of maritime disputes became a job for the United Nations. Talks would go on, acrimoniously, until in 1982 the United Nations Law of the Sea agreed on 12-mile territorial zones and 200-mile exclusive economic zones. Almost everyone signed up, with the notable exception of the US.

Why had states found it so hard to agree? Partly because new ways to exploit and control the seabed had emerged, like submarine cables and oil drilling. No one wanted to miss out on those. But disputes were also increasing because fishing vessels were getting larger, and stocks were dwindling.

As British fishermen ventured further and further north in search of the cod and haddock that customers demanded, the newly independent state of Iceland acted. It extended its exclusion zone and banned foreigners from fishing within 12 miles of the coastline. Britain ignored it. Iceland extended the zone again.

The Icelandic coastguard tried to drive British fishing vessels away, sometimes even ramming them, while the fishermen stood on deck and hurled potatoes as missiles. These early “battles” had an element of comedy. Gradually, however, the clashes intensified. Icelandic boats sailed over British fishing nets and cut through them. The Royal Navy sent patrols to deter the Icelandic coastguard. In 1973, Britain gave in and agreed to catch fewer fish. It didn’t last. Two years later, Iceland pushed its exclusion zone out to 200 nautical miles and the “cod war” broke out again.

Since Britain considered that entirely unacceptable, Iceland took a new approach. It warned the US that it might no longer agree to host Nato infrastructure unless the UK conceded. Just as had happened in Suez, America ordered the British to retreat, and we obeyed.

Losing the cod wars is one of the reasons why the British fishing industry has shrunk so much. Yet for the fishers, worse was to come. A few years after Britain joined the EEC, the Community created its own exclusive economic zone that, like Iceland’s, reached 200 miles from its shores.

All member states had equal access to fish in the zone, and gradually the EEC took on more responsibility for managing stocks. This led to the deep-seated resentment about Brussels interference that was ably exploited by the Leave campaign in 2016; 92% of fishermen said they would vote to leave.

The UK insisted that it must be deemed an “independent coastal state” in the Brexit trade and cooperation agreement. It did us no good. “There is little doubt that overall the UK fishing industry is worse off after Brexit,” says Robin Churchill of the University of Dundee. The industry is especially furious that EU vessels can fish just six miles from our coastline.

The fact that British fishers feel they got such a poor deal the first time around will make it all the harder to renegotiate a satisfactory agreement. They hope that nations like Finland, where Russia is an immediate threat, will put pressure on France to agree to a security deal without demanding too many more fish.

But they have underestimated the unity of the European Commission before, and tensions are high in France. In January, a British fishing boat used a grappling hook to drag apart the cable and net on a French trawler, in what a French minister called an “exceptionally serious incident”. Denmark is angry, too, after the UK banned sand-eel fishing in an effort to protect shrinking stocks of the main food of the puffin, whose populations have fallen as a result.

As the summit approaches, Reform and its media outriders are casting around for an opportunity to stir up the atavistic nationalism that served it so well during the referendum. Fish are the ideal way to stoke up anger: throw in the hungry puffins, too, and some conservationists will be won over.

An easy catch, you might say. But Vladimir Putin will be watching.