The Shetland Islands are not a big place. Around half the size of Shropshire, they are home to just over 23,000 people, or around one-17th of the population of the London borough of Croydon. By the time of the winter solstice, the days are less than six hours long. The wind is relentless. Aberdeen is a flight or a rough 12-hour ferry trip away.

But life on Shetland has some compensations. For households in the district heating scheme, hot water is cheap, and the profits are reinvested in the islands. The archipelago has no fewer than eight public swimming pools, six leisure centres and a newly rebuilt library. Brae high school, one of the two secondaries, is about to be redeveloped as a community hub.

Where does the money for these things come from? Why is Shetland doing pretty well, thanks, while Croydon has declared itself bankrupt three years running?

Shetland is able to provide generous facilities – and also to dole out regular grants to local charities and community services – because half a century ago it did a very good deal. The man largely responsible for negotiating it, county clerk Ian Clark, died last July.

Clark was an “astonishingly hard nut”, remembered Robert McCrone, who was one of the civil servants in the Scottish Office working on North Sea oil. “I think he probably pushed his luck a bit far on occasions, but he actually did a splendid job for Shetland.”

McCrone attended a seminar organised by the Science Museum a quarter of a century ago whose purpose was to understand how the decisions were made about how to exploit North Sea oil and gas. By that time, it was understood that fossil fuels might be superseded, but that seemed a long way off: the first British offshore wind farm had yet to start producing electricity.

All the witnesses who spoke at the event were men. Most are now dead, and the rest proved impossible to track down, as I discovered when I was researching North Sea oil for an episode of the Jam Tomorrow podcast about postwar Britain. (A history of Concorde had the same problem: the sole surviving witness from that seminar was Lord Heseltine, who sent his regrets.)

Yet the further it all recedes from living memory, the more important it becomes to understand why the discovery of oil seemed to have had so little tangible impact on the lives of most Britons. We struck lucky. But we never quite seemed to acknowledge it.

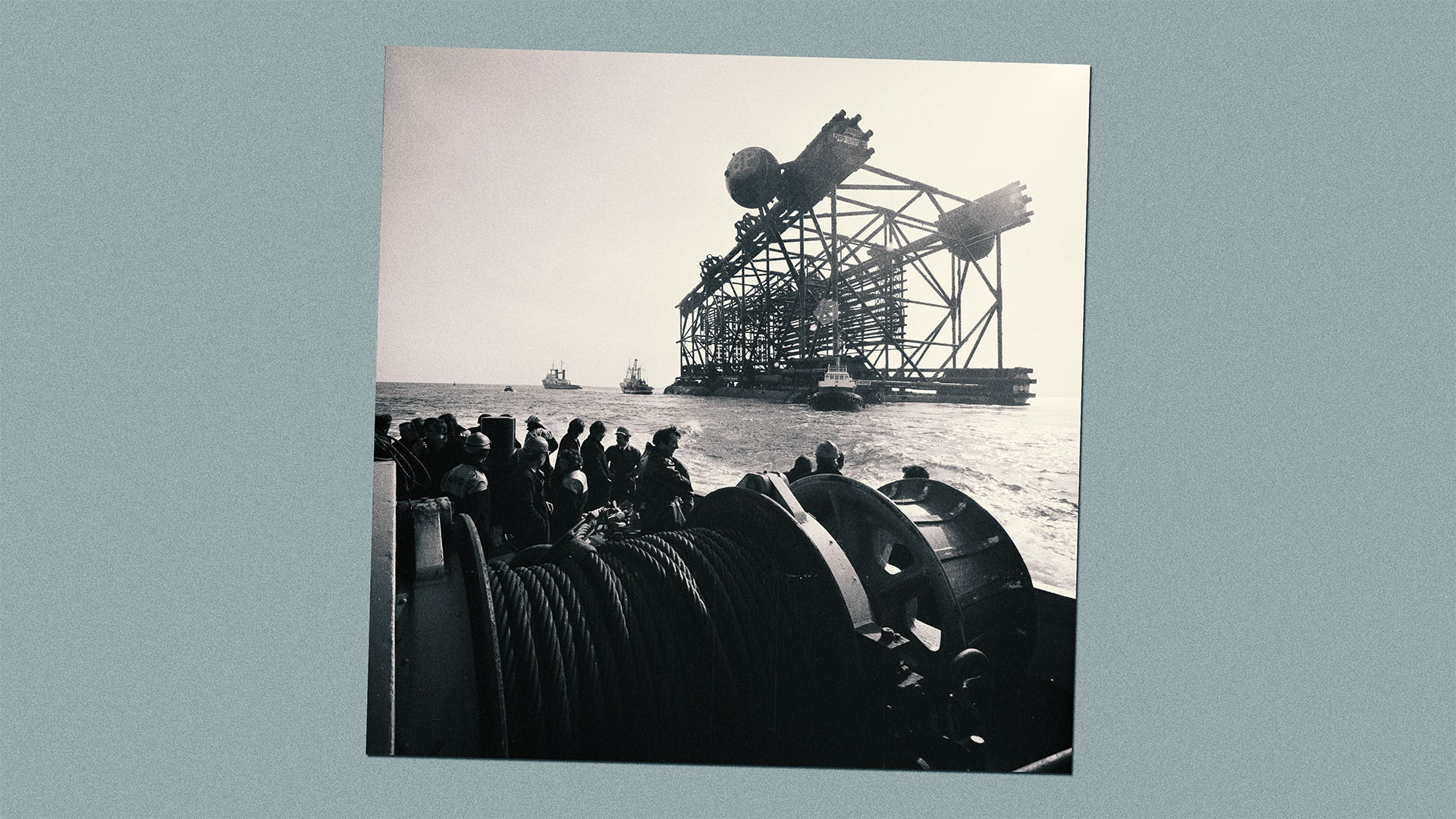

The story started in the early 1970s, as it became clear that North Sea oil would need to be piped ashore somewhere on the Shetlands. The islands suddenly became the object of fierce interest from oil firms and construction companies.

The Treasury was not prepared. McCrone remembers a very senior official asking whether the Shetlands were one island or two (in fact, 16 of them are inhabited). “Because Shetland on most maps is stuffed into the Moray Firth, nobody actually knew quite where it was.”

They soon did, flying into an airstrip grazed by sheep and lit by paraffin lanterns. Clark, whom one Shell executive complained was harder to deal with than Colonel Gaddafi of Libya, did a fine job in ensuring there would be just one oil terminal, at Sullom Voe, instead of each company building its own. But he wanted more than that – and because the government needed the Shetlands’ cooperation so badly, he got it.

To compensate Shetlanders for the new terminal, Clark negotiated a deal whereby the Shetland Charitable Trust would get annual payments from oil companies. By the turn of the millennium, when the payouts stopped, it had received over £81m. Judicious investments – the trust uses four fund managers, including Baillie Gifford and BlackRock, and has invested in Shetland’s district heating scheme and the Viking windfarm – mean it now has around £400m in assets.

The Shetlands prosper from their good fortune and are likely to continue to do so, even if North Sea oil and gas production ends and Sullom Voe is decommissioned.

A one-off deal by a local council is easy to dismiss as exceptional. It was: it required an Act of Parliament. But it wasn’t only Shetland that benefited from the oil rush. The Treasury did, too. While taxes on North Sea fuels bring in relatively little revenue now, they used to be much higher. In the mid-1980s they accounted for more than 3% of GDP.

The potential scale of the windfall was apparent by 1977: “God has given Britain her first opportunity for a hundred years in the shape of the North Sea oil,” James Callaghan, then prime minister, told the Commons.

Margaret Thatcher was concerned: “My worry is they aren’t going to use it for expansion at all. They’re going to use it rather like a person who’s won the football pools… just for living on,” she told Panorama.

What did Thatcher use it for after she won power in 1979? The taxes and royalties weren’t hypothecated, of course, and it is impossible to say exactly how the Conservatives would have managed the economy without them. But the surge in unemployment in the early 1980s, along with a cut in the top tax rate from 83% to 60%, made big demands on the Treasury.

Nor was the effect of the oil boom wholly positive. As McCrone pointed out, it pushed up the exchange rate, which contributed to the high unemployment of the early 1980s. “So North Sea oil revenues were paying for the unemployed to a very substantial extent,” he says. It wasn’t quite what Thatcher or Callaghan had wanted.

“Bizarrely,” says Jon Gluyas, a professor at Durham University who worked for BP after he finished his PhD in 1981, “the day Margaret Thatcher walked through the door of Number 10, the UK became a net exporter of oil and gas.” At peak production, the revenues made an “absolutely enormous” contribution, he says: profits were taxed at 95% through a complex combination of different measures. “The UK was buoyed, like the Middle East has been, by being extremely productive.”

Unlike many countries, however, the government decided to scale back its direct involvement in the sector. It privatised the British National Oil Corporation (BNOC) and sold off its stake in BP. Well before those decisions, though, was the question of issuing licences for oil exploration. How much should firms have to pay?

Nothing, it turned out – partly because no one knew how much oil was under the seabed. As for gas, it was even more of an unknown quantity. Later, oil firms were accused of underestimating North Sea reserves, something they vehemently denied.

“That was probably the first big mistake that was made in the North Sea,” Colin Robinson, now an emeritus professor at the University of Surrey, told the seminar. “Because the licences were given out for free, instead of being auctioned as they could have been, it meant that the government realised afterwards that there was going to be a problem of trying to realise what they thought was rent or excess profits from the North Sea.”

There were other missed opportunities. Alastair Morton was the managing director of BNOC during the late 1970s. He later oversaw the building of the Channel Tunnel. “The will to look at oil as something that was of important political economic interest disappeared.”

At one point he tried to strike a deal to hold oil in reserve for the rest of the European Economic Community – something they were keen to do after experiencing a series of oil price shocks. In exchange, Britain would not have had to pay into the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). “I was making good progress with the idea until the Foreign Office had a fit,” he said.

The question of whether Britain would have left the EU if our financial obligations were smaller is one for the counterfactual historians. In the early years of Euroscepticism, the alleged greed and wastefulness of the CAP was a common source of resentment. You can at least say that the £350m on the side of the Vote Leave bus would have lost some of its impact.

Just as with the current windfall tax on oil companies, ministers were trying to keep the price of gas down for the public and simultaneously extract as much money as possible from wealthy firms. So Thatcher’s approach was to raise taxes on oil companies during her first term, but also to try to make exploration cheaper.

She regarded BNOC as a bureaucratic brake on enterprise. In 1982 it was split in two, and the oil exploration and production sector part-privatised before BP finally took it over in 1988.

It could all have been very different. Plenty of people who had to work with BNOC agreed with Thatcher and saw it as government red tape getting in the way of making money.

But for others it was a missed opportunity. They looked across the North Sea to Norway and saw the clout of its national oil company, Statoil, and the way it invested in processing plants and championed the country’s oil industry. Why couldn’t Britain do that, rather than leaving it all to the multinationals? “It would have concentrated the mind of the British public on how important oil was,” said the petroleum economist Peter Odell, who died in 2016. “And we lost opportunities in Europe… Norway realised, unlike this country, the importance of the commodity for its wellbeing.”

Eventually, Statoil was part-privatised and merged with the Norsk Hydro firm, and is now called Equinor. But perhaps the biggest regret for some politicians was Britain’s decision to spend all the proceeds of oil rather than investing them in a sovereign wealth fund like Norway’s.

Although it is called the Government Pension Fund, the money invested in it from 1996 onwards – all $1.74tn, which you can watch fluctuate in real-time on the Norges Bank Investment Management website – is not paid in by individual Norwegians. It comes from oil revenues and is only invested abroad. Each year the government takes out a sum that is no more than the fund is expected to grow in the same year. Yet it still amounts to around a fifth of Norway’s budget.

A British sovereign wealth fund could never have been as generous as Norway’s, because their population is so much smaller than ours and our operating costs are higher. The introduction of the windfall tax in the UK meant that both countries now levy approximately the same tax rate on oil. But for a certain type of lefty economist, Britain’s failure to plan for the time when the oil and gas would run out will always be unforgivable.

“We did think a great deal about an oil fund,” said McCrone. “But the whole idea was dropped immediately when the government changed in 1979… What the government did was to set up the Scottish Development Agency.”

That was trivial stuff as far as many Scots were concerned, and no one was (and sometimes still is) more resentful than the Scottish National Party.

Draw a line east across the North Sea from the Scottish border, superimpose British oilfields, and you can see why. During the 1970s and 1980s it stuck in the craw of many Scottish nationalists that much of the oil wealth would end up being spent by Westminster.

“It’s Scotland’s oil,” ran party ads in 1972, picturing proud, despondent Scots. “So why are there so few jobs for Scots? Why do we have the worst unemployment rate in industrial Europe? Why are so many Scots old folk cold and undernourished?”

In the early years, “North Sea oil was managed by Westminster and the Scottish Office in Edinburgh in a muddled and naively non-commercial manner,” said Sir Iain Noble, who admitted to trying to rip off a Sullom Voe crofter by buying his land for a song, before having an attack of conscience and doubling the price he paid.

Scotland, and especially Aberdeen and the Shetlands, did benefit from the oil boom. So did the rest of the UK. But it was overwhelmingly Scotland that saw the hard work that went into extracting it.

What this meant, as the historian and SNP politician Christopher Harvie has pointed out, was that as far as most of the English were concerned the oil came out of nowhere. Rigs and pipelines had no place in the collective political and cultural imagination.

Most of us have never seen a North Sea platform, let alone been to one. the Piper Alpha disaster in 1987, when a platform exploded and killed 167 workers, was shocking not just for its horror, but also for the realisation that so many men lived in such remote and inhospitable places. The men – and it is overwhelmingly men – who are responsible for getting oil and gas out of the seabed are never celebrated or pitied as miners were.

Disaster, when it happened, was further away and felt less visceral. As Harvie wrote, “the impact of the oil on the British metropolitan intelligentsia and its imagination was practically zero.”

Again, Norway had a completely different attitude. It opened a museum in Stavanger celebrating its oil and gas, and considers decommissioned rigs – which, once dismantled, usually leave no trace above the waves – part of Norway’s industrial heritage. Hardly anything is left of Frigg, a Franco-Norwegian rig that at one point provided a third of the UK’s gas, but its history and way of life, even down to details of the food the workers ate, is documented online.

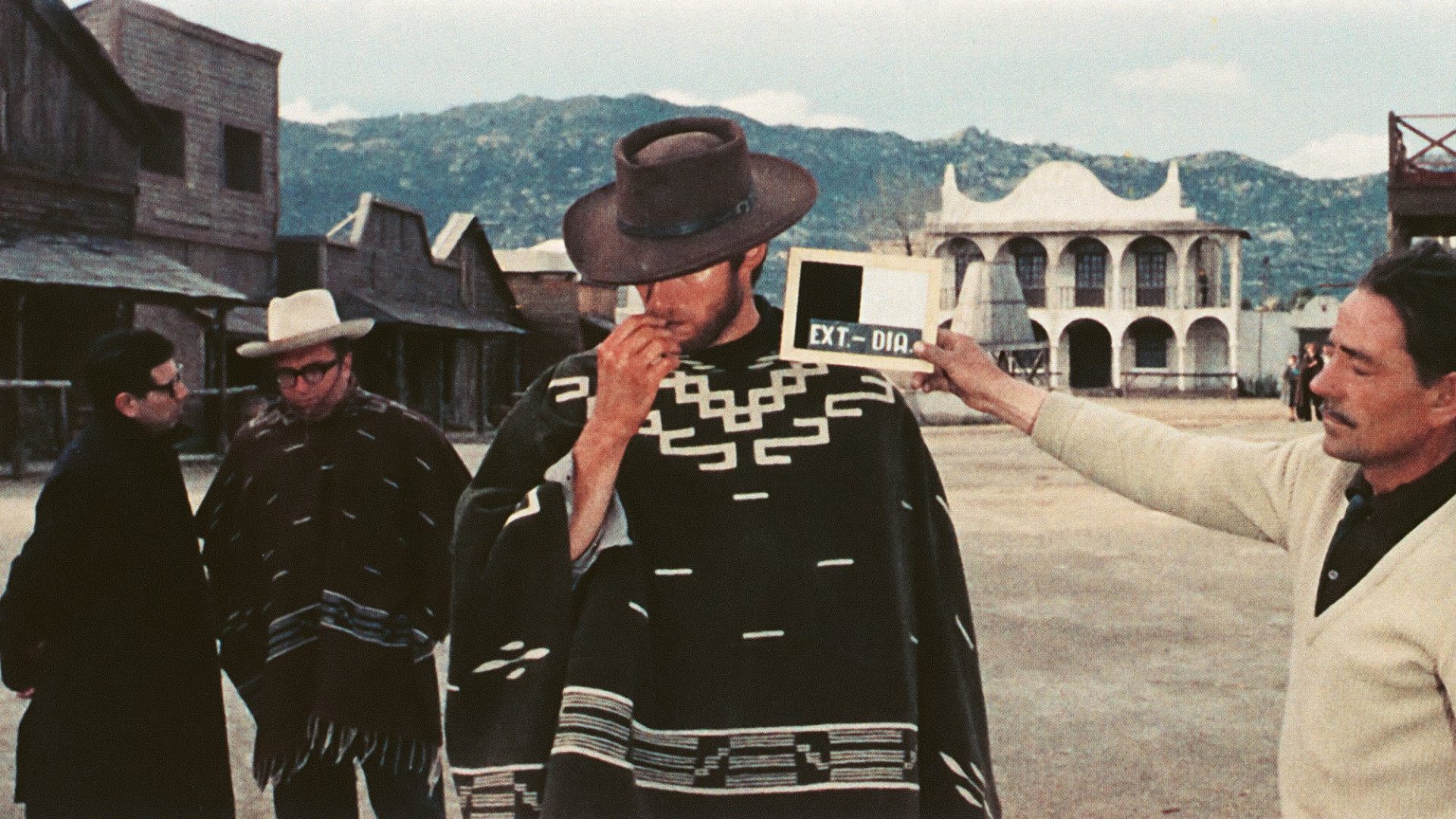

Peter Iain Campbell is a Scottish photographer who spent a year working as a steward on rigs and documenting the workers and the structures where they lived. I asked him what it was like for the people who had worked on the rigs for decades and knew that the era of North Sea fuels was nearly over.

“It’s a difficult transition. It’s harder for them because they’ve become so used to that world.” Relationships built up over many years were coming to an end. As for the rigs themselves, “I’m simultaneously haunted, overwhelmed and in awe – you know, disturbed by them… seeing these platforms and drilling rigs in a condition where they’ve endured 40 years of the North Sea climate and those conditions.

“I like to have this more meditative approach photographically, because there’s no doubt the effect the burning of fossil fuels has had on our environment.”

The dream of a sovereign wealth fund is over. The Shetland Charitable Trust, no doubt conscious of how much it has benefited from fossil fuels, now wants to generate all the islands’ electricity from wind.

Empty oil and gas fields are an ideal place to store captured carbon, and some North Sea workers will be encouraged to retrain in that industry.

Next year it will be half a century since Queen Elizabeth opened the Forties oilfield. Britain is moving on. But for the Shetlands, one man’s stubbornness continues to pay off.

Ros Taylor hosts the Oh God, What Now?, Jam Tomorrow and Bunker podcasts, and is the author of The Future of Trust (Melville House)