The Nordic model of social welfare and capitalism has many attractions, but it can lack excitement. For Monty Python, Finland was the country “where I long to be/ Pony trekking or camping/ Or just watch TV”.

But while no country is perfect, most European nations stand out in at least one field. It might be for the generosity of their welfare state, or the importance they attach to defence, railways or food. Taking the best of Europe and amalgamating it into a utopian state is a wildly unrealistic proposition and completely unaffordable. Putting those caveats aside, what would it look like?

Finland does have many admirers. It may no longer be at the top of the European PISA ratings for 15-year-olds’ performance in maths, science and reading (Estonia and Ireland have overtaken it), but it is the only European country to have almost eliminated homelessness. This has been achieved by giving homeless people a flat to live in – an obvious solution, on the face of it, but one that most countries would not dare to present to their voters. Outreach teams actively seek out people sleeping rough to encourage them to get shelter. It helped that the proposal originally came from a centre right politician and is often justified in pragmatic terms (it reduces the burden on healthcare and makes cities more attractive) rather than moral ones (people have a right to a place to live).

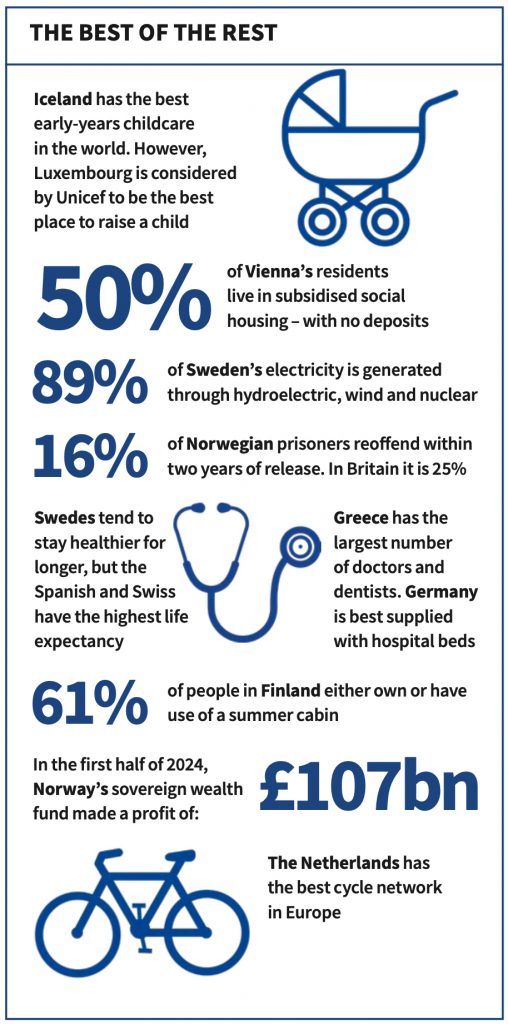

Finland has an unusually high rate of second-home ownership, which may make Finns less likely to resent their generous policies on homelessness. Summer cabins undoubtedly contribute to the Nordic quality of life: 61% of Finns either own one themselves or can use a friend’s or relative’s mökki in the countryside.

As part of a University of Helsinki study in 2021, when asked what they did all day at their cabin, three teenage boys replied: “We warmed up the sauna nearly every day and… swam. And went into the sauna. And rowed a boat. We have played a lot of cards. And checked the fish trap, and things like that. That’s the basics.” More fun than watching TV, then.

Neighbouring Sweden has many second homes (stuga) too. But it can also be an enjoyable place to work. Overtime is relatively rare and, in some companies, the tradition of breaking off from work twice a day to chat over coffee and cake is mandatory. Employees are usually allowed to take four consecutive weeks off during the summer. In terms of emissions, Sweden is the cleanest country in Europe. Hydroelectric, wind and nuclear power together account for 89% of electricity generation. Most of the rest is supplied by biofuels.

All the Nordic countries have liberal prison systems, but Norway leads the world in locking people up in a humane and productive way. It has small prisons, jails an unusually low proportion of its citizens, and only 16% of them reoffend within two years of release. In Britain, would-be prison officers get nine weeks of training. Norway stipulates a two-year programme at a dedicated academy. The difference is apparent in the principles of normality that apply to Norwegian prisoners: their sentence is simply the restriction of their liberty, rather than other rights, and the aim is for life inside to resemble life outside as much as possible.

In Norway, prisoners may start out in a high-security jail, but then progress to a more open prison, and finally a “halfway house”. It is understood that the more institutionalised a prisoner becomes, the harder it will be for them to rejoin society.

Funding decent prisons is undoubtedly easier when you have a sovereign wealth fund to draw on. Unusually, Norway’s fund has an ethical mandate and was created in the 1990s as an investment vehicle for surplus oil and gas revenues. It made a profit of 1.48tn kroner (£107bn) in the first half of 2024. All this largesse comes from selling fossil fuels abroad, and the scrupulous might well object to that – but it does mean that Norway’s welfare state is well-funded, especially care for the elderly.

While many Norwegians do informal tasks for their ageing parents, few have to care for them full-time, which means more women are able to take paid work. Still, even here the universalist principle is starting to erode. Recent studies reveal that local authorities increasingly offer different levels of care and are paying relatives to do it rather than providing it themselves.

The quality of Iceland’s early-years childcare is high – the best in the world, according to Unicef – but it is relatively expensive. The parents of the youngest children have to pay around £400 a month, which is cheap by UK standards but costly in comparison with Italy and Germany. Unicef considers Luxembourg the best place to raise a child, because parental leave is generous and so is the ease of finding a place to live.

Luxembourg excels in another respect. It spends far more on community sport than any other EU country. Over-50s have a scheme called Club Senior to encourage them to exercise and socialise, and children get a free health check-up every two years.

The Nordic diet is high in fish and whole grains, but it can also rely heavily on butter and cheese. Greeks eat less saturated fat than other Europeans and more fruit and vegetables. The question of which country’s food is the most delicious is beyond the scope of this article, though Italy surely has a claim.

Judging which country has the best healthcare is difficult, because so many factors are used to measure good health. Swedes tend to stay healthier for longer, but the Spanish and Swiss have the highest life expectancy. The Irish are most inclined to believe they are healthy. Italy has the lowest rates of obesity (though these are self-reported, so not entirely reliable).

Switzerland and Germany spend the most on healthcare, but if you have a stroke it is in Norway that you are least likely to be dead a month later. Greece has the largest number of doctors and dentists per head of population, but the Dutch see the dentist most often. Germany is the country best supplied with hospital beds. Overall, then, Germany and Switzerland win out – although you may fret less about your health in Ireland and Italy.

Increasingly, a generous welfare state does not necessarily mean that a country leans to the left. Hungary’s nationalist government, for example, has introduced extremely generous benefits for parents. Families with three or more children get tax breaks and help with their mortgages, and new parents can stay at home for up to three years on full pay. But none of these benefits is universal. Only heterosexual, married couples who already have jobs qualify. Viktor Orbán says these policies affirm the importance of women and families. Critics say they privilege the white, Catholic middle class.

Neighbouring Austria will almost certainly have a far right prime minister this year. It “sounds a very socialist country but actually it’s not,” says Thomas Hauer, an Austrian citizen. Half of Vienna’s residents live in subsidised flats. Contracts are open-ended, with no deposits, and the income threshold is deliberately high to encourage social mixing. “No other European city can boast a similar constancy of its social housing policy – a policy that was never abandoned, not even when the spirit of the era was dictated by neoliberalism and privatisation,” says vice-mayor Kathrin Gaál. Vienna has never sold off any of its housing stock.

Austrian universities, too, are cheap. Some science students pay around €1,000 a year in fees, but the rest pay none unless they take a long time to finish their course. There are no student loans because maintenance grants are given on the basis of merit or need. If students are under 25, their parents even get a tax break.

The transport system is excellent (an annual travelcard for Vienna costs €365) and the KlimaTicket, which covers all public transport for a year, is €1,179. Austria’s trains are slightly more punctual than Switzerland’s. The Czech Republic also has a surprisingly wide-ranging and frequent railway network. The Netherlands, inevitably, has the best cycle network.

In the performing arts, there are three main contenders for the winner: Ireland for its local theatres and music scene (and the craic, obviously), Britain for the quality and range of West End productions, and Germany for classical music, opera and the Long Night of the Museums in summer, when they stay open until 2am. For modern architecture, Spain probably wins out; for design, Denmark. Italy spends a lot of money on its museums and archaeological sites and has nearly 5,000 of them, twice as many as the UK.

Unfortunately, we can’t just rate countries on their quality of life. Our utopia is in Europe and is therefore vulnerable to Russian aggression. Would it be able to defend itself against hybrid warfare or even an invasion? A few years ago, very few countries would have been able to answer that question confidently. Only the UK and France, which spend about the same on defence, would have had a decent chance of repelling an attack. The French have slightly more soldiers and aircraft, while the Royal Navy has more destroyers and submarines – but critics point out that not all of them are operational at any one time.

As European countries come to terms with the war in Ukraine and the possibility that Donald Trump will abandon Nato, this is changing. Eastern European nations are spending far more on defence. Poland now has 130,000 full-time soldiers and is by some measures the biggest army in Europe. Lithuania, as one of the strongest opponents of Russia in eastern Europe, wants to spend 5% of its GDP on defence. A combination of Royal Navy expertise, modern French ships, the Armée de l’Air and Polish troops might offer the best hope of fending off an attack.

How much does all this cost? If we consider Germany, Finland, Switzerland, Austria, Norway and France together to represent the most generous and effective spenders and look at their tax revenue as a share of GDP, it works out at an average of 42.6%. That is a lot more than Britain spends now (33.5%), but by 2027 things will have changed (37.7%) – just a whisker behind Spain.

This exercise of trying to imagine the perfect European nation disproves one Eurosceptic myth. Populist parties have long warned that the EU represents a threat to national identity and the cultural and political differences that make European countries so enjoyably different.

In fact, they still have very different customs and spending priorities. There really is no such thing as a utopia.

Ros Taylor hosts the Oh God, What Now?, Jam Tomorrow and Bunker podcasts, and is the author of The Future of Trust