“Vous-êtes Sissi, n’est-ce pas?”

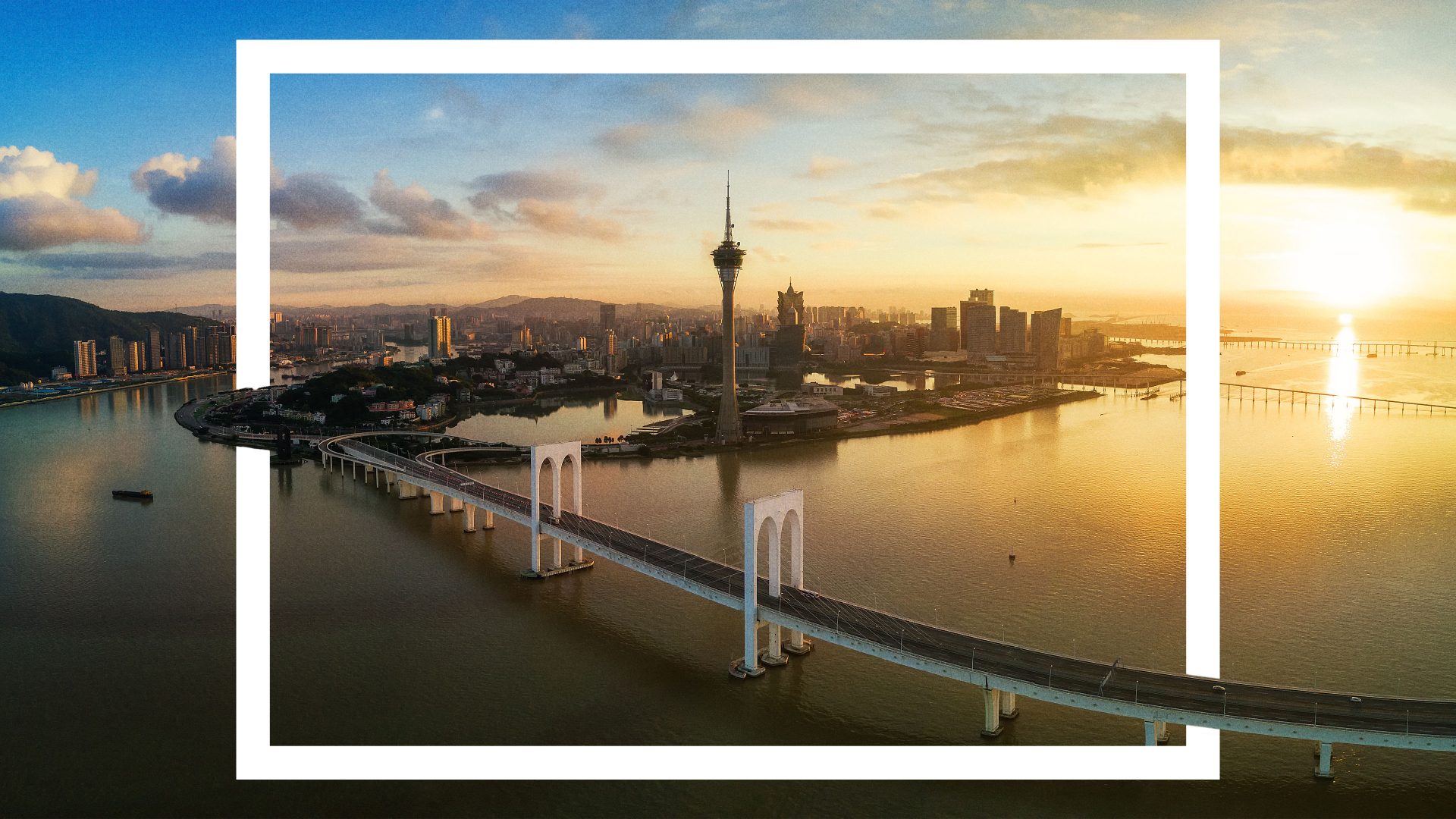

Quiberon is a tiny isthmus off the southern coast of Brittany that’s joined to the mainland by a short causeway so narrow it could almost qualify as an island. Brittany, thrusting into the Atlantic, feels like the end of Europe. Quiberon hangs from the bottom of its sleeve, an ending leading from an ending.

In the spring of 1981, Romy Schneider had arrived at Quiberon’s spa resort for a few days’ detoxification from the alcohol and pills on which she had become reliant. She was about to begin filming an adaptation of Joseph Kessel’s novel The Passerby but that wasn’t why she’d come to Brittany. Divorce proceedings from her second husband, Daniel Biasini, were about to commence and her 14-year-old son, David, from her first marriage to the German film director Harry Meyen, had indicated he would prefer to live with his stepfather when they separated.

It was for David she was cleaning up, to prove she was worthy of him.

Quiberon was the perfect escape. Schneider had visited regularly since moving to Paris from Germany 20 years earlier and as well as the treatments and detoxification she longed for the freedom offered by the Atlantic horizon and the wildness of the coast. Each day would begin with a hosing down in freezing water, there would be massage treatments and an ascetic diet. She would return energised and healthy, ready to win back the trust of her son.

Yet she couldn’t quite cut herself off completely. Schneider had invited Germany’s Stern magazine for an interview, mostly because the photographer, Robert Lebeck, was an old friend. It was risky – Germany had never forgiven her for moving to France – but she felt that if she was cleansing her body, her mind needed cleansing too.

A completely fresh start lay ahead; the second half of her life would be different once the first had been laid to rest.

Lebeck and the journalist Michael Jürgs arrived the day before the scheduled interview and suggested they get together that evening at the harbour bistro, to loosen up ahead of the formality of the interview.

It wasn’t long before the table filled with champagne flutes, buckets and bottles, detox forgotten. Then a local fisherman walking past the table stopped, looked at Schneider and asked if she was Sissi.

Playing the 19th-century Empress Elisabeth of Austria turned the teenage Schneider into a star. The 1955 biopic Sissi remains one of the most successful German-language films of all time, drawing more than 25 million people through the box office and inspiring a trilogy. Too old to be a child star, Schneider’s wholesome, ringleted screen appearance in the saccharine film still saw the German press dubbing her “Shirley Tempelhof”.

Sissi represented the pinnacle of German Heimatfilm, a sugary postwar genre of morally unambiguous period films, and was so popular Schneider left Germany altogether to escape its shadow. And escape she did, working under directors like Luchino Visconti, Claude Sautet and Orson Welles, and starring opposite Jack Lemmon, Peter Sellers and Rod Steiger in a career of impressive versatility and range. Yet wherever she went Sissi always seemed to be at her shoulder, sticking to her, as Schneider once complained, like oatmeal.

She looked at the fisherman and exhaled a long stream of cigarette smoke. “Non,” she said firmly. “Je suis Romy Schneider.”

Born in Vienna six months after the Anschluss, Schneider was the fourth generation of a formidable acting dynasty. Her father, Wolf Albrach-Retty, was an early star of German cinema and an enthusiastic Nazi while her mother, Magda Schneider, became Adolf Hitler’s favourite actress. The family would spend their summers at a house close to Hitler’s holiday residence at Berchtesgaden and Schneider even claimed her mother had an affair with the Führer.

Magda, understandably struggling to revive her career after the war, encouraged Schneider to act, seeing in her beautiful and talented daughter a route to rehabilitation.

“I need to become an actress,” Schneider wrote in her teenage diary.

“I just have to.”

Whether that represented genuine ambition or a sense of duty to her mother remains, like many aspects of Schneider’s life, ambiguous, but within two years she was a household name.

Schneider met Alain Delon on the set of 1958’s Christine, a remake of a 1933 film in which Magda played the same role, and fell instantly in love. The French actor also presented an opportunity to escape Sissi for a new start in Paris. “I want to be completely French, with regard to the way I live, love, sleep and dress,” she said, a snub Germany would never forget.

For five years Schneider and Delon were Europe’s most glamorous couple until the day in 1963 when she returned from filming in America to find a bunch of red roses and a note, “Dearest Romy. I have gone to Mexico with Nathalie.” The woman in question – model Nathalie Barthélémy – soon became pregnant with Delon’s child. He’d already fathered one, with model/singer Nico, during his relationship with Schneider.

Caught up in this new level of celebrity and media scrutiny, Schneider became known as much for her private life as for her films. Even though her marriage to Meyen had ended in 1975, his suicide in 1979 – he had never recovered from the trauma of being tortured by the Gestapo – brought the press flocking to her door.

And here, in Quiberon, with a rare opportunity for solitude and a recalibration of her lifestyle, she had volunteered to give an outrageously candid interview that remains infamous in Germany.

In the bistro, Lebeck snapped photographs of Schneider dancing with the fisherman. The next day, all of them hungover, she unburdened herself with an unfiltered honesty that startled Jürgs. She talked about her mother, her relationships, her dependence on alcohol and pills, her children. She chain-smoked. She veered between boisterous exuberance and tearful introspection.

It might have been a performance. It wasn’t. Schneider was clearly vulnerable, but Jürgs kept his tape recorder running and Lebeck kept taking pictures. “We wanted an interview, she wanted a conversation,” shrugged Lebeck later. “She needed support, I needed photos.”

The next morning Schneider skipped around the large boulders on the beach for Lebeck’s lens until she fell and broke her foot. Returning to Paris, she spent a month recuperating at home, during which she approved the text of Jürgs’ interview for publication. She felt buoyant for the enforced rest and the absolution provided by the interview.

It was the last contentment Schneider would ever know. She was barely back on her feet when searing back pain forced an emergency operation to remove a tumorous kidney. While recovering in hospital, her son David died in a freak accident, impaling himself while climbing on railings.

A year after Quiberon, Schneider was found dead sitting at her desk. Halfway through writing a letter cancelling a magazine interview, she had suffered a heart attack.

In Quiberon, Jürgs had barely switched on his tape recorder when Schneider lit a cigarette, gazed out of the window and declared, “I am just an unhappy 42-year-old woman and my name is Romy Schneider”.