Last words tend to carry more significance than they possibly should, especially in the event of an unexpected death. We all hope to leave something profound hanging in the air before we go but most of us will shuffle off this earthly plane having tossed out something unexceptional and banal.

In rare cases, however, a person’s last recorded thoughts are appropriate enough to carry a distinct poignancy.

Roland Topor’s last 24 hours before his sudden death from a brain haemorrhage at the age of 59 began with him circulating among a succession of his favourite Paris cafes in a haze of cigar smoke and the uncorking of some excellent burgundies.

Between greeting friends in different establishments, Topor’s thoughts kept returning to a nightmare from which he had awoken the previous night. It had been a dream whose vivid and disturbing images were impossible to dismiss even hours later.

He was still thinking about the dream the next morning when he holed up as usual at the Café de Flore before flinging aside the newspaper he was failing to read and realising his nocturnal subconscious was nagging at him precisely because it had gifted him the perfect opening to a new novel.

He opened his notebook and wrote: “I am awakened suddenly by a feeling of imminent disaster. Turning down the sheet I discover a cadaver in my bed, the husk of a man of small stature, but fat, around my age.

“My first reflex is to jump to the telephone and summon the police – but I hesitate. The presence of this rotting carcass in my bed is embarrassing: explanations will be demanded of me that I will be incapable of furnishing.

“They will suspect me of a crime that’s abominable.”

Within hours of writing those words, Topor was dead, leaving the novel unwritten. But the dream had provided an epitaph inadvertently appropriate for a man who spent his life producing art and literature that shocked and appalled the unsuspecting and saw him frequently condemned for abominable crimes against decency.

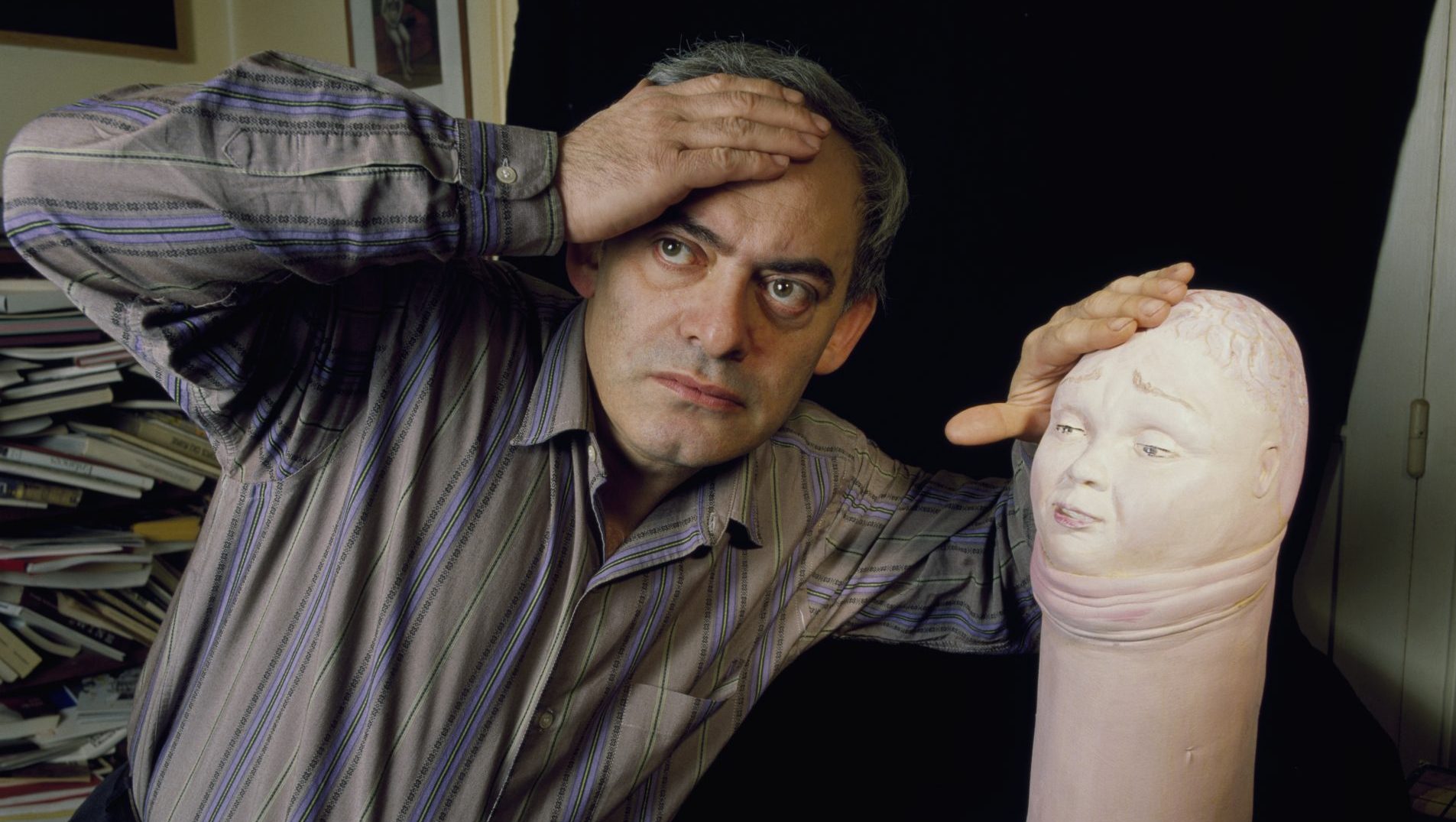

The polymathic Topor – novelist, artist, playwright, illustrator, actor and film-maker – made a career out of the grotesque, macabre and scatological, creating shockingly dysfunctional stories, characters and images that revolved around what he summed up as “le sang, la merde et le sexe” – blood, shit and sex.

He thrived upon brandishing these everyday substances and activities at his audience, battering through taboos to produce work like the play Vinci avait raison (Vinci Was Right), a satire of whodunnits and possibly influenced by JB Priestley’s An Inspector Calls.

Topor’s play is set not in a country mansion in a quaint English village but in a house that none of the characters can leave and where the toilet is blocked, prompting huge mounds of excrement to appear on stage as the production progresses.

When Vinci avait raison was performed in London in 1978 most of the audience left before the end, while in Brussels a year earlier one critic had been moved to demand: “We must put this idiot in prison for creating such filth. This is a question of the public moral good”.

While many writers and artists might have been delighted at provoking such a reaction, Topor wasn’t interested in people who walked out or critics who would throw away the key, he cared about the people who stayed and the critics provoked into thoughtful responses to his work, which, far from being mere shallow attempts to shock, was always carefully crafted and deeply considered.

“One gram of shit is enough to ruin a kilogram of caviar,” he said, “but one gram of caviar does nothing to improve a kilogram of shit.”

Arguably his defining literary work was the Kafkaesque 1964 novel Le Locataire chimérique, translated into English as The Tenant, about a Polish immigrant who moves into an apartment in Paris after the previous occupant threw herself out of the window.

A darkly comic novel that was adapted for cinema in 1976 by Roman Polanski, Le Locataire chimérique sees its protagonist Trelkovsky desperate to belong somewhere, to leave a sense of himself in a place that feels like home, yet he finds himself snubbed by everyone else in the building.

“Others would come into it and kill off forever any lingering assumption that a certain Monsieur Trelkovsky had ever lived here,” he muses about the future of his abode. “Unceremoniously, from one day to the next, he would have vanished.”

This combination of leaving a trace and being tormented by neighbours was the most overt expression in his work of the trauma at the core of Topor’s being.

In 1941 he was three years old and living with his Polish-Jewish parents and sister in the 10th arrondissement of Paris. One day his father Abram, obeying instructions, went to register with the Vichy regime only to find himself packed into a truck with other Jews and sent to a concentration camp at Pithiviers. Sensing that a worse fate lay in store further east, he managed to escape and go into hiding. Of the 3,700 Jews interned with Abram Topor at Pithiviers, barely 150 would survive the Holocaust.

Meanwhile, the Topors’ landlady lurked on the landing of their apartment building trying to wheedle Abram’s whereabouts out of the children, intending to inform the authorities. In the summer of 1942, however, ahead of a Gestapo sweep of the street, the Topors fled south with Abram to Savoy. While not in as much immediate danger as in Paris, Topor was placed with a sympathetic local family and lived out the war under an assumed name attending a local Catholic school.

After the war the family returned to Paris, successfully suing the landlady for the return of their apartment and belongings and moving back in, passing on the stairs almost daily the woman who had attempted to have them sent to the camps. Little wonder that Topor set out his artistic statement in uncompromising fashion.

“I want my existence to be a supreme affront to the vultures who have become so impatient since the 1940s,” he said, “by way of an uninhibited representation of blood, shit and sex.”

Throughout his career he was determined to assert his place in the world by turning everything else inside out, making the world the alienated thing, transforming the taboo into the everyday through his writing and his art.

“If I put a hand in place of a head some people will say, ‘how disgusting’,” he said. “Yet such a reaction is pathological.

“I seek to enlarge the field of play a little by the disruption of things that appear too stable or immutable. Personally I do not believe in this stability; we set things in stone far too easily.”