In the spring of 1956, 28-year-old Roger Vadim sensed he was on the brink of

greatness. Filming was about to commence on And God Created Woman, his own script under his own direction, and his wife, the 21-year-old Brigitte Bardot, was in the starring role.

He’d had an inkling Bardot was destined for stardom but her early roles, some of them in films he’d written, had failed to capitalise on the simmering

sexuality whose exploitation he believed would catapult them both on to the

world stage. And God Created Woman was the perfect film for the times, he

felt, and with his and Bardot’s presence behind and in front of the camera, as

well as the revolutionary new Cinemascope lenses bringing the Mediterranean seascape to widescreen, they were sure to be at the vanguard of a new era in European cinema.

Vadim’s script placed Bardot at the centre of a St Tropez love triangle with two brothers while a much older, wealthier man circled in the background. Unlike in most cinema of the time it was Bardot’s character who held the power, both physical and emotional, used in a manner previously exclusive to male romantic leads.

Groundbreaking for its time, And God Created Woman would cause a sensation, inciting religious organisations on both sides of the Atlantic to huffing about debauchery and immorality despite the film being coy by modern standards, the nudity implied rather than explicitly revealed, and Bardot’s character behaving only as a string of male characters had almost since the dawn of cinema.

While the film launched Bardot to international fame, the same could not really be said for Vadim. He had correctly identified the particular screen appeal of his wife and the film was beautifully shot – it would transform St Tropez into one of Europe’s most sought-after destinations – but the plot was flimsy and characterisation superficial at best.

The New York Times published a typical review, salivating breathlessly over “this round and voluptuous little French miss… a thing of mobile contours, a

phenomenon you have to see to believe”, before settling down to a less enthusiastic appraisal of Vadim’s contribution.

“She is undeniably a creation of superlative craftsmanship,” the review

read, “but that’s the extent of the transcendence for there is nothing

sublime about the script of this completely single-minded little picture.”

Thus was the recurring theme of Vadim’s life and career set out. He would

recognise the screen appeal of and cultivate relationships and marriages

with some of the screen’s most beautiful women, but his filmmaking, while

frequently original and ambitious, too often lacked the depth and craft to match their stellar presences.

As well as Bardot, he counted Jane Fonda among his spouses and had a long

relationship with Catherine Deneuve. The presence of these eminent women on his arm would define his public perception far more than his films ever would, but it was something he appeared largely content to propagate.

“I have a fantasy that when I die I will arrive at the gates of heaven and St

Peter will be there,” he said in a 1984 interview. “He will say, we are pleased to see you, you have been a good man and in a moment I will show you to your place. But first, tell me this… how were Deneuve, Bardot and Fonda when they were young? What were they like? When they come up here they will be old ladies and we will never know. So tell me, what were they like?”

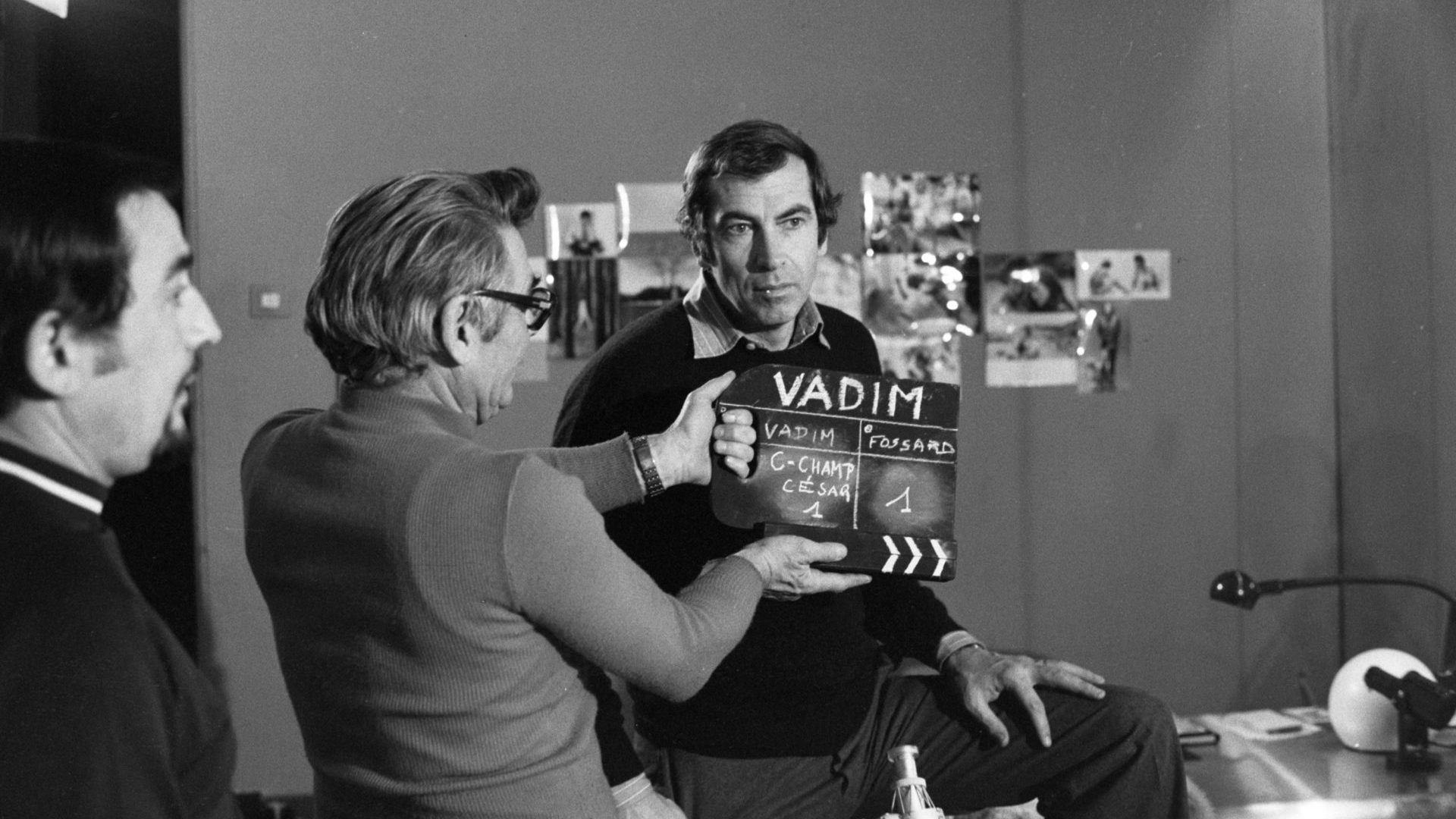

It was the question he was asked everywhere he went and he revelled in being its subject to the point of pondering a saint leaning in and breathing heavily in search of the lowdown. Ideally, Vadim might have preferred his 1986 autobiography to focus on his respectable cinema career, in which he was credited by some with helping pave the way for the nouvelle vague, but he chose instead to call it Bardot, Deneuve and Fonda: My Life with the Three Most Beautiful Women in the World.

There was more to Vadim than his relationships. He was born Roger Vadim

Plemiannikov in Paris, the son of Igor, a former officer in the Imperial Russian army who had moved to France, become a naturalised citizen, married actress Marie-Antoinette and risen in the French diplomatic service to become vice-consul to Egypt. Vadim spent his early years in Alexandria

before a move to Turkey where Igor died when his son was nine, prompting

a return with his mother to France.

Marie-Antoinette remarried and the family moved to the Alps, where their

home became a key sheltering point for Jews attempting to escape to Switzerland during the war: a close childhood friend of Vadim’s was among locals burned alive in a barn by the SS for anti-Nazi activities.

A postwar move to Paris saw Vadim become a journalist reporting for Paris

Match, but when the 19-year-old met and became assistant to the director Marc Allégret, cinema became his destiny. A gifted writer, Vadim contributed to Allégret’s screenplays until in 1954 he received his first solo writing credit on the Hedy Lamarr vehicle Loves of Three Queens.

By then he was married to Bardot, whom he’d met when as a 15-year-old

she auditioned unsuccessfully for a role in an Allégret film. Romance blossomed and the couple married in 1952 when Bardot was 18. Vadim had worked on screenplays for Bardot’s early film appearances but it was the success of 1955’s Naughty Girl that led to his being handed directorial control of what became And God Created Woman.

Vadim’s hopes of the film launching the couple to global acclaim would be unfounded, however. As well as lukewarm reviews of Vadim’s craft, Bardot had begun an on-set relationship with co-star Jean-Louis Trintignant that

led to divorce. Vadim then briefly married Annette Stroyberg before embarking on his relationship with the then 18-year-old Deneuve in 1962, with whom he had a son a year later.

He met Fonda on the set of La Ronde in 1964, married her the following year and went on to direct her in arguably his best film, the 1968 science-fiction fantasy Barbarella. From that creative high point, however, Vadim’s career went into gradual but terminal decline until the nadir of an attempted 1988 reboot of And God Created Woman starring Rebecca De Mornay that was a critical and box-office disaster.

Cinema had moved on in the three decades since the original but Vadim was

still trying to recapture the heady days of the mid-1950s when, in the St Tropez sunshine, he felt a world of cinematic opportunity opening before him to which he would never be fully admitted.

There were two more marriages after Fonda, including to Catherine Schneider whom he described, apparently approvingly, as “not an actress and not beautiful”. The marriage didn’t last.

When he died at the turn of the millennium, Fonda, Bardot, Stroyberg

and Schneider all attended his funeral at the Cimetière Marin de Saint Tropez – a cemetery that had been one of the filming locations for And God Created Woman.