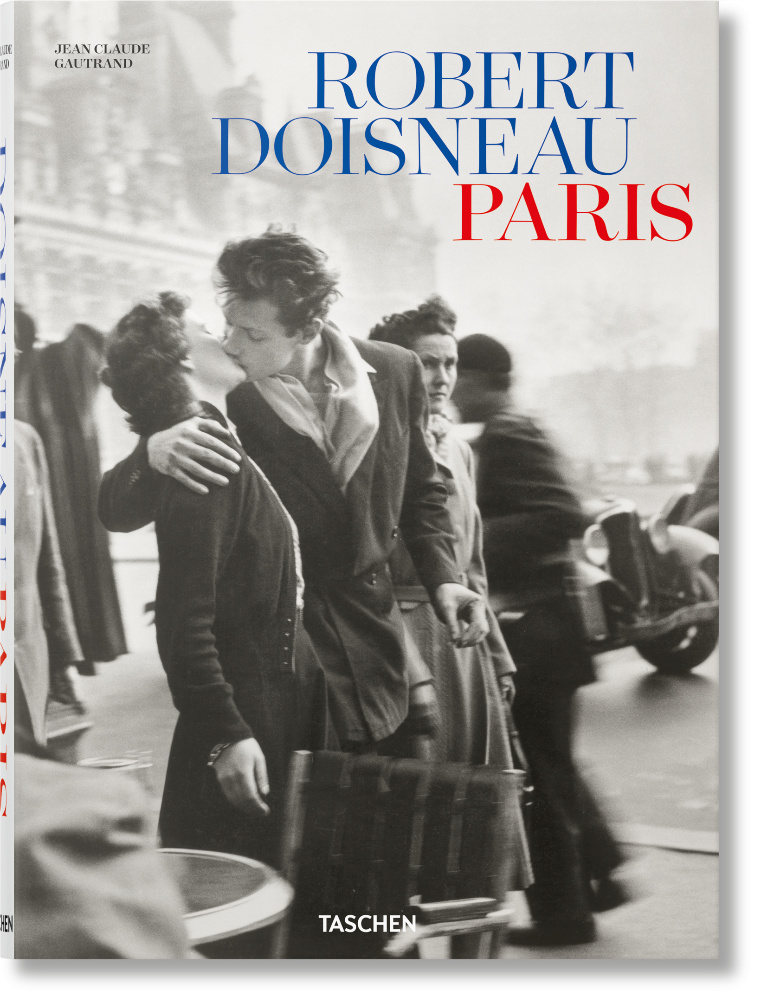

We might not know his name, but for one kiss. There it is, on a million postcards and prints, and on the cover of Taschen’s beautiful 440-page new collection Robert Doisneau. Paris. But for 1950’s Le Baiser de l’Hôtel de Ville (The Kiss by the Hôtel de Ville), Robert Doisneau may still have been regarded as he was in a period the book calls “The Lean Years” – a man whose time had passed.

Often we learn of how an event in one’s youth shapes an artist. Doisneau’s mother died of tuberculosis when he was young, and for 10 years he walked past her grave every day on his way to school. It’s impossible not to see this as having informed some of the melancholy of his work.

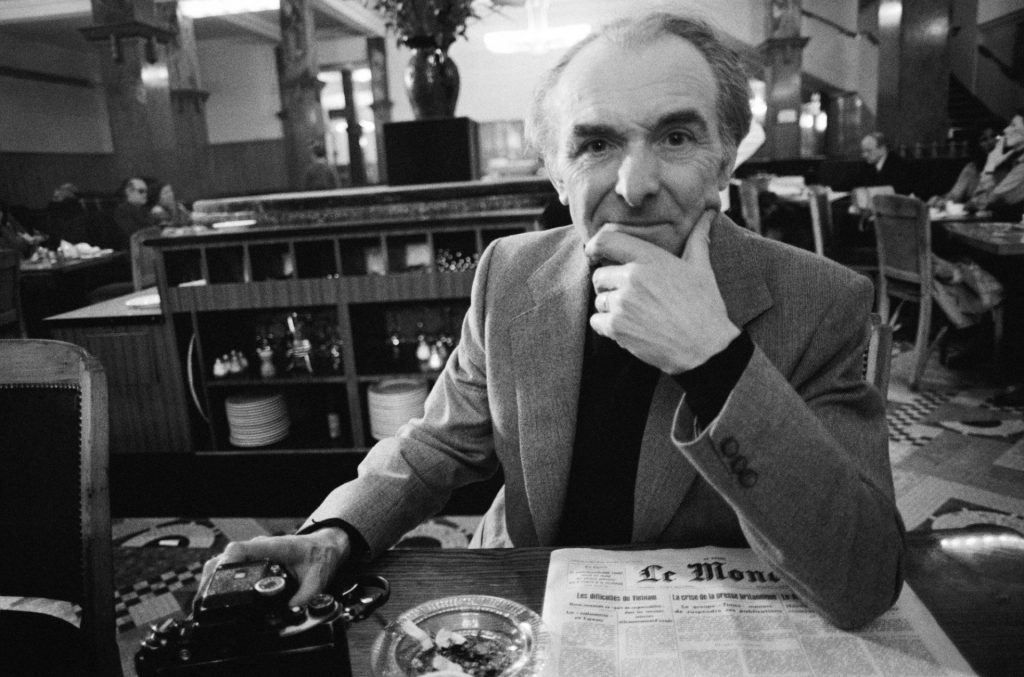

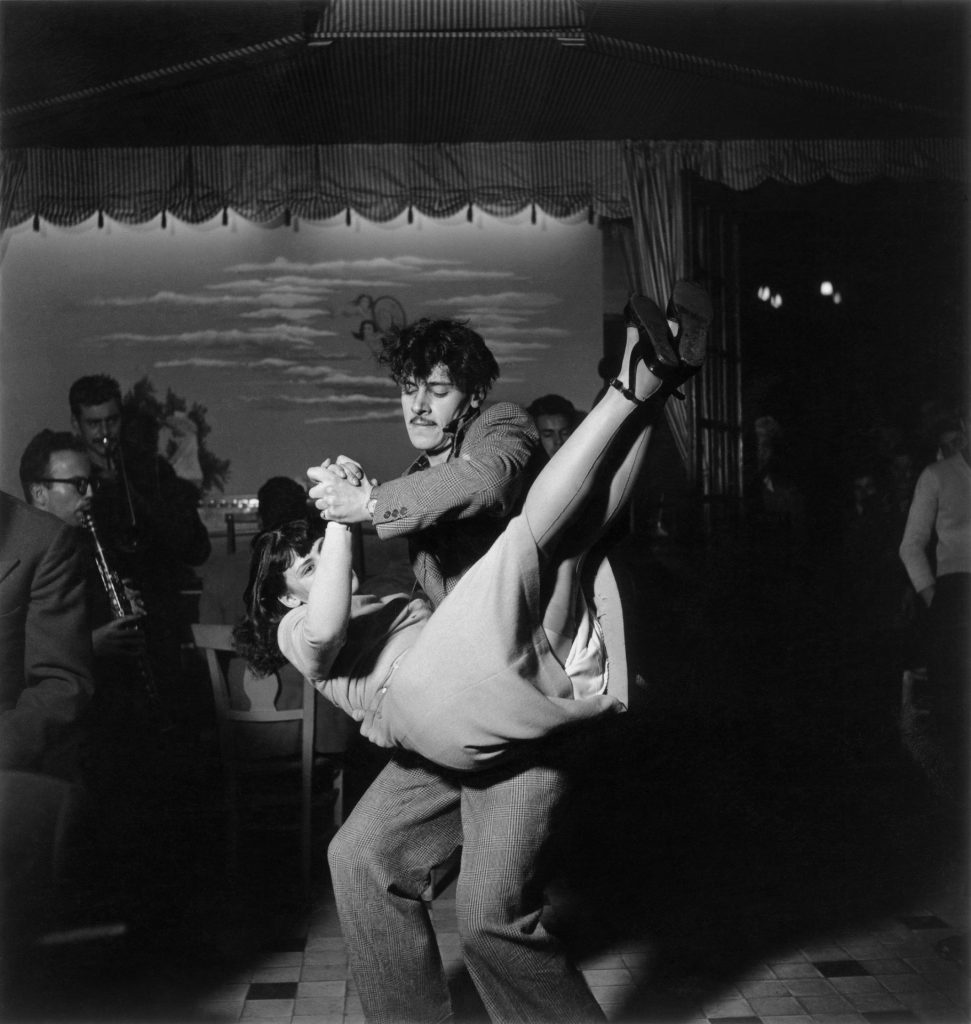

There is a wistfully romantic air to his visions of Paris – “I don’t photograph life as it is, but life as I would like it to be,” he said. He largely eschewed the powerful and monied, rarely straying beyond HIS city. He fed mongrel cats, marvelled at rats for whom the Seine was their river, rabbits populating the bushes under the Eiffel Tower. He loved the Parisian people getting on with their business, or having a good knees-up.

“One of the great joys of my career has been to meet and speak to people I don’t know,” he once said. “Often these simple people turn out to be delicious characters who create a poetic climate. One should only ever take photographs when overflowing with generosity for others.”

By the start of the 1960s, Doisneau had won two major photography awards and published 15 books of his images. He was working for the prestigious agency Rapho, and occasionally for Vogue and Life magazines. But grittier work was in vogue, which did not bode well for a man who made his pictures so simple that they could not be misinterpreted.

Doisneau began to be passed over as blandly humanistic, lightweight. Even his memorable photo from the events of May 1968, The Burnt-Out Car, Latin Quarter, speaks of his despondency at what his Paris was becoming. By the end of the 1970s he was photographing celebrities and working for the advertising industry.

But the growth of commercial licensing and of poster stores like Athena, together with a single image out of the 450,000 he took during his lifetime, restored Doisneau’s reputation.

In early 1950, he had pitched to various American magazines the idea of a series of photographs of lovers in Paris. Life commissioned him. The photographer then spotted drama students Françoise Bornet and Jacques Carteaud kissing in a cafe. With their permission, he followed them around the streets.

The most famous of the images he took that day, a moment caught at the corner of rue du Renard and rue de Rivoli, conforms to our romantic image of Paris – a place where time stops for lovers, the stars of their own movie, as the supporting cast of ordinary Parisians pass by. Published on June 12, the photograph was acclaimed and republished.

Ironically, given what would happen to Doisneau, people loved it because it seemed a harbinger of a different, more relaxed, postwar world.

But its second life, in which the picture was now a nostalgic image of a lost time, brought more money, and more problems. Court cases seeking a share of the pie were brought by people who believed they might have been the ones caught in the image (they weren’t). Then, when it became widely known that Doisneau had set up the photo, it was dismissed as phoney. That the couple in it were actual lovers who had been recompensed for their efforts did not seem to matter.

Doisneau certainly did not think it wrong that his famous picture was staged. He admitted it was so. His longtime friend Jean Claude Gautrand, who edited the Taschen book, writes that in The Kiss by the Hôtel de Ville, Bornet and Carteaud “deliberately tread the boards of the little theatre set up by the photographer… in the same way as all those anonymous characters who crossed his path throughout his life and left him one-hundredth of a second of their existence.”

And what a memorable one-hundredth of a second the three of them shared. The Kiss by the Hôtel de Ville, a photo that was once forward-looking and then nostalgic, is timeless. Or, as Doisneau explained: “The photographs that interest me, the ones I find successful, are those that reach no conclusion, they never tell a story right to the end, they leave things open so people can keep company with the image a while and continue it as they see fit; a sort of stepping stone for dreams.”

Stuart Roy Clarke is an English documentary photographer. His major works include The Homes of Football