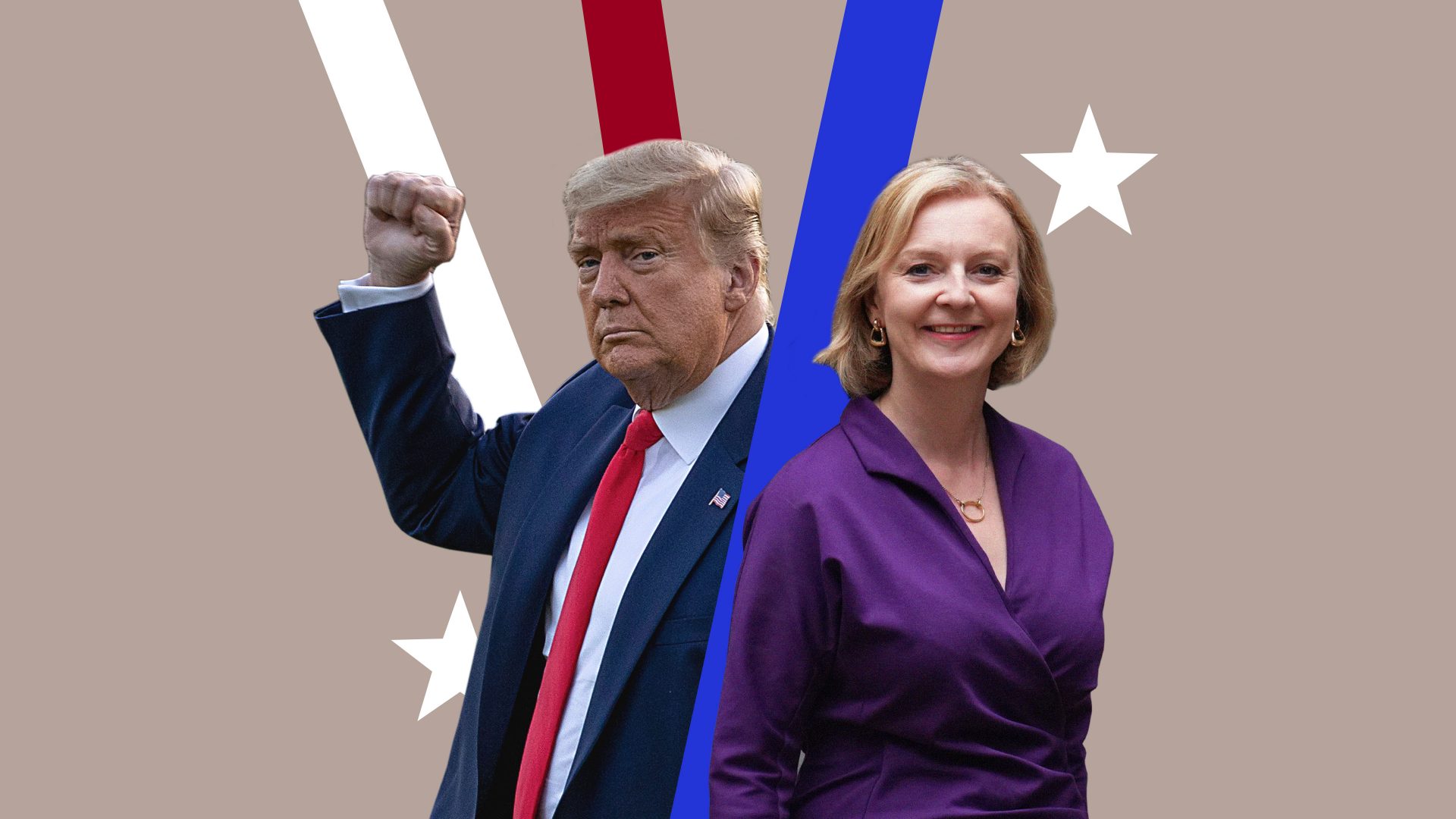

I was half an hour into a meeting with senior government officials when the news broke. Liz Truss had just resigned, the shortest-serving prime minister in British history bringing to an end a rule that, even by contemporary British politics, was ignominious.

A small group of experts had been called into Admiralty House to provide external advice on an update the government is planning to its “integrated review” on foreign, defence and security policy. This is good work, done by good officials, trying to provide a guidebook on dealing with Russian aggression, the strategic challenge posed by China, building new relations with Europe and combating climate, migration and other longer-term challenges. A number of other countries are doing the same.

We discussed the world, but throughout the four-hour session, neither the Whitehall folk nor the think tankers could resist frequent glances at their phones for updates. There was no excitement. More a jaundiced, morbid curiosity about what would happen next and who would come next.

There is only so much that civil servants can do as they watch the latest episode of the British nightmare unfold. That the Conservatives’ psychodrama is taking place at a time of maximum global crisis is not lost on them. That Boris Johnson, the man who had most brought the country’s reputation into disrepute, had indicated from his luxury Caribbean hide-out his desire to return to save the nation, was certainly not lost on them.

As Rishi Sunak and Penny Mordaunt fought over the entrails of the Tory leadership, as Johnson plotted and then withdrew from his Clownback, Russia was unleashing further Iranian drones over Ukraine and Xi Jinping was consolidating his power over the Chinese Communist Party, ushering in a new and sinister phase of his quest for hegemony.

Economists, diplomats, military and security experts – indeed anyone with any intelligence – are doing what they can to keep Britain afloat. The Ministry of Defence continues to issue its much-praised reports on the latest situation in Ukraine. The Bank of England, Office for Budget Responsibility and other financial institutions are seeking to insulate the country from the worst shocks of the next week or so. Would Jeremy Hunt even get to issue his budget on October 31, completing the unpicking of Trussonomics?

Each time the UK hits a new low, another one comes into view. Journalists have run out of words, images, memes to describe it. Mayhem, chaos, disaster, turmoil don’t begin to describe it. The Economist ( just before Truss quit) likened Britain to Italy, much to the Italians’ fury. Der Spiegel ( just after Truss quit) called Britain “the banana island”, with the subheading: “How the Brits have become the laughing stock of Europe”.

It is not hard to feel sympathy for headline writers or London-based foreign correspondents. What more can they say? Some have taken to simply reporting the expletives offered up by Tory MPs, without the need to translate them.

One of the paradoxes of the trauma of the past two months is the realisation dawning on some of those who put their two dummies into office that the strange dreams on which their adventure was based – their Singapore-on-Thames fantasies – are shot. Truss’s 44 days will be remembered by her wooden response to the death of the Queen and the extreme ideology that gave rise to the horror budget and the run on the markets.

Yet she took one decision that may, just may, set Britain on a better course. Her acceptance of an invitation – from friend/foe President Emmanuel Macron of France – to attend the inaugural meeting of the European Political Community in Prague on October 6 may prove the turning point in relations with the EU.

The aim of the gathering of 42 nations (the EU 27 plus 15 others) was to “foster political dialogue and cooperation to address issues of common interest” and “strengthen the security, stability and prosperity of the European continent”. The chief topics were to be energy security and other forms of infrastructure resilience in light of Vladimir Putin’s actions in Ukraine. It was all vague enough for Truss, finally, to agree to go.

It seemed to have finally dawned on Downing Street that, while “mini-lateral” deals with the Nordics and the Baltics have proven important, Britain cannot plausibly continue to both antagonise and ignore the EU. It is hard to do both, but it has so far managed exactly this.

A few days earlier, eyebrows had been raised on the first day of the Conservative conference when Steve Baker, an arch-Brexiteer, a former chair of the European Research Group and now a Northern Ireland minister, said: “It’s with humility that I want to accept and acknowledge that I and others did not always behave in a way which encouraged Ireland and the European Union to trust us to accept that they have… legitimate interests… because they do, and we are willing to respect them. And I’m sorry about that.”

Baker’s comments may help to explain why Micheál Martin, Ireland’s Taoiseach, said he thought the UK government was now serious about getting a solution to the Northern Ireland Protocol. It has long been accepted at the Foreign Office (FCDO) and in Brussels that a solution to the Irish border question is technically fairly simple to negotiate. “It could be done in a day with goodwill,” says one diplomat.

It was politics that prevented that and politics could continue to do so, judging by the statement given by Baker’s former chums in the ERG on Monday lunchtime. The chairman, Mark Francois, declared that both Sunak and Mordaunt “were equally adamant they’d take, if they became prime minister, a very robust line on the Northern Ireland Protocol, up to and including, if necessary, utilising the Parliament Act to ensure that NI Protocol bill reaches the statute book”. It will come down to a battle between extreme ideology and national self-interest.

Another important but largely hidden development was the decision to allow the UK to join the EU’s Permanent Structured Cooperation (Pesco) framework, which encompasses around 60 military projects. The project on military mobility does not amount to a joint military force, but is aimed at making rapid joint military deployments easier. Sensible decisions, taken by largely sensible people, largely behind the scenes.

Inevitably, these first green shoots were blown away by the chaos surrounding Truss’s departure and the leadership contest that ensued. Logic (for what that’s worth) suggests, however, that relations with the EU will have to be patched up, whether the arch-Brexiteers want it or not. The economics are just too terrible for anything else.

This, at least, was the message contained in a stunning commentary in one newspaper that spoke of a “calamitous loss of standing” for Britain as it battles to maintain its status on the world stage. There is nothing stunning in stating the blindingly obvious, for sure. What mattered was the who and the where. This was assistant editor Jeremy Warner in the Brexit Bible, the Daily Telegraph.

He wrote: “Downbeat predictions by the Treasury and others on the economic consequences of leaving the EU, contemptuously dismissed at the time by Brexit campaigners as ‘Project Fear’, have been on a long fuse, but they have turned out to be overwhelmingly correct, and if anything have underestimated both the calamitous loss of international standing and the scale of the damage that six years of policy confusion and ineptitude has imposed on the country.”

The job of diplomats is to deal with whichever government is in power. World leaders have got used to sending messages of congratulations and notes of condolence to incoming and outgoing British prime ministers.

The Clown is dead: long live the Clown. British political buffoonery has been priced in. Much of the work behind the scenes carries on regardless.

Three days before Truss’s departure I was chairing another event. Two dozen experts had come to Britain from 18 countries – from Albania to Zimbabwe, Saudi Arabia to Lithuania, Chile to Turkey, India to France – to answer the question: “What does the world expect of Britain?”

It was intended not to pick over the entrails of now, but to cast forward to the end of the decade. The assumption was of a 2024 general election and a five-year term run by a sensible prime minister. Everyone was too polite to mention who was being referred to.

What should Britain do? What should it leave to others? What can it control, and what can it not control? Where does it sit in the world? (“Medium power” apparently). What are its key assets?

Remarkably, there was a curious optimism, a reservoir of goodwill that had diminished but was by no means drained. The words that used to be applied to Britain – solid, reliable, dependable, trustworthy – have been blown away since 2016.

Will Sunak start, let alone succeed, down this path towards international rehabilitation, or will he be undermined by his own beliefs as a Brexit early adopter, and by the many mad Tory forces within? Many world leaders will be willing him on, not because of any special place of the UK in their affections, but because its ructions have been an unwelcome distraction.

For comedians and foreign correspondents, Britain has been the gift that keeps on giving. If over the next two years Sunak succeeds in making it less entertaining, he will go down as the best Conservative leader of the 21st century. That, admittedly, is not an especially high bar to clear.