The battle for Ukraine is mutating, from an almost certainly lost cause to a just cause with a chance.

In the days since Russia began the vicious assault on its neighbour the international mood music has gone from funereal to belligerent. Social media posts from the warzone are inundated with alternately sad, funny and hopeful stories attesting to the Ukrainian people’s unbroken morale. And the Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky’s emotional appeal to “citizens of the world” to join his country’s fight for its life as a sovereign nation is gaining traction.

Volunteer fighters from Britain, the US, Germany and elsewhere are answering the call to arms and heading for Ukraine. The UK foreign secretary, Liz Truss, went on national TV to declare she would “absolutely” back anyone wanting to volunteer to help the Ukrainians because they “are fighting for freedom and democracy, not just for Ukraine, but for the whole of Europe”. Typically, the government then rowed back on this – saying it would be illegal and the best way to stop Vladimir Putin was to make donations instead – but dozens of British citizens have already made their choice and are in, or on their way to, Ukraine.

Might Ukraine become a historical hinge point for idealistic initiative when confronted by the forces of tyranny, just like the Spanish civil war in the 1930s? In Spain in 1936, when a broad coalition of Republicans loyal to the left-leaning Popular Front government fought against General Franco’s fascists, citizens of liberal democracies took up the weapons that their officially non-interventionist governments were leery of deploying.

The list of people who believed defence of the Spanish republic was a cause worth fighting for is long and distinguished. It includes George Orwell, Laurie Lee and Ernest Hemingway, all of whom would later write about their experience, its brief flash of hopefulness and prolonged dreadfulness.

The parallels with Ukraine at this point are mainly about the fine precedent set by volunteer efforts to try and turn the tide of war. The 1930s battle for Spain was cast as one for humanity’s progress. It lit a fire. In Homage to Catalonia, Orwell’s 1938 account of volunteering for the war, he writes: “To anyone from the hard-boiled, sneering civilization of the English-speaking races there was something rather pathetic in the literalness with which these idealistic Spaniards took the hackneyed phrases of revolution… All this was queer and moving. There was much in it that I did not understand, in some ways I did not even like it, but I recognized it immediately as a state of affairs worth fighting for.”

Are Ukrainians’ belief in democracy and freedom as values to live by – and die for – similarly worthwhile for the sneering West? After Zelensky called for “friends of Ukraine, peace and democracy” to join the fight to “save Europe”, his government created an “international brigade” of volunteers and urged foreigners to head to Ukrainian embassies worldwide to sign up.

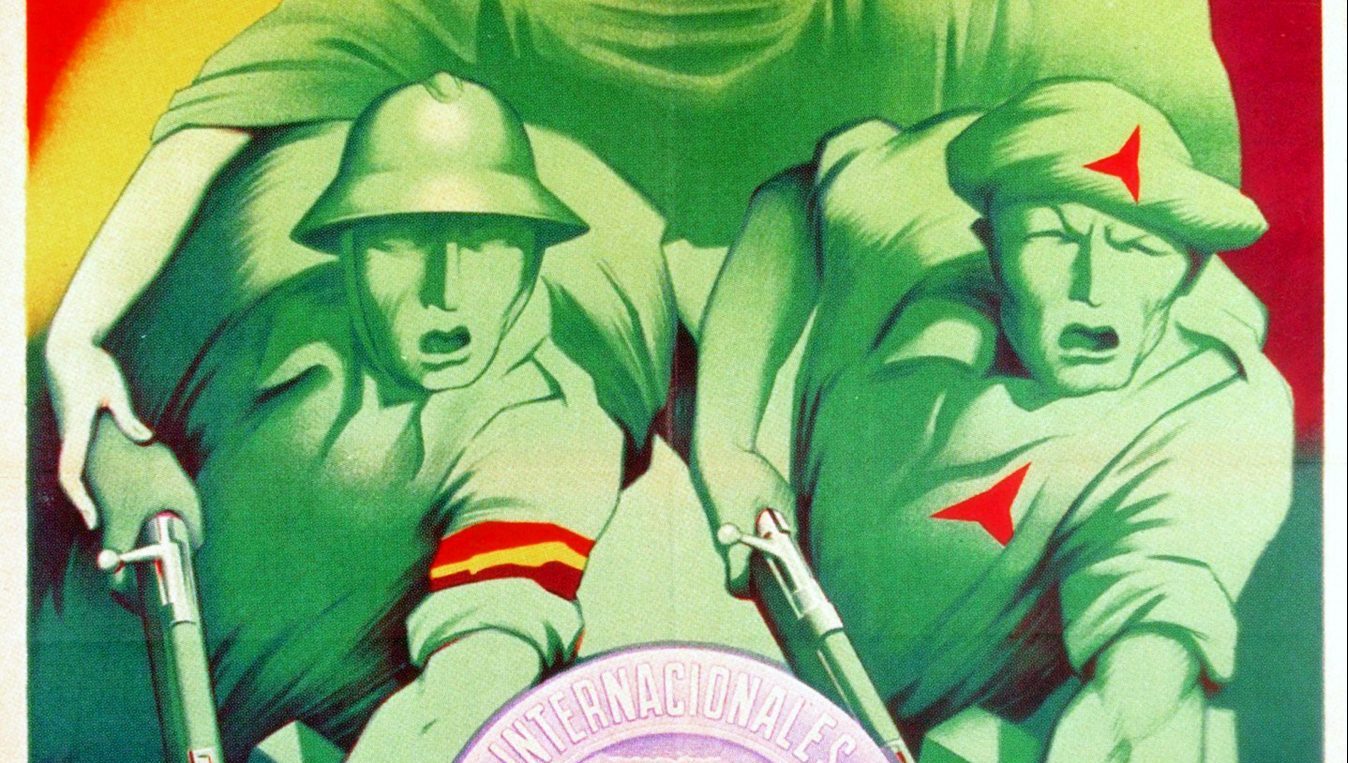

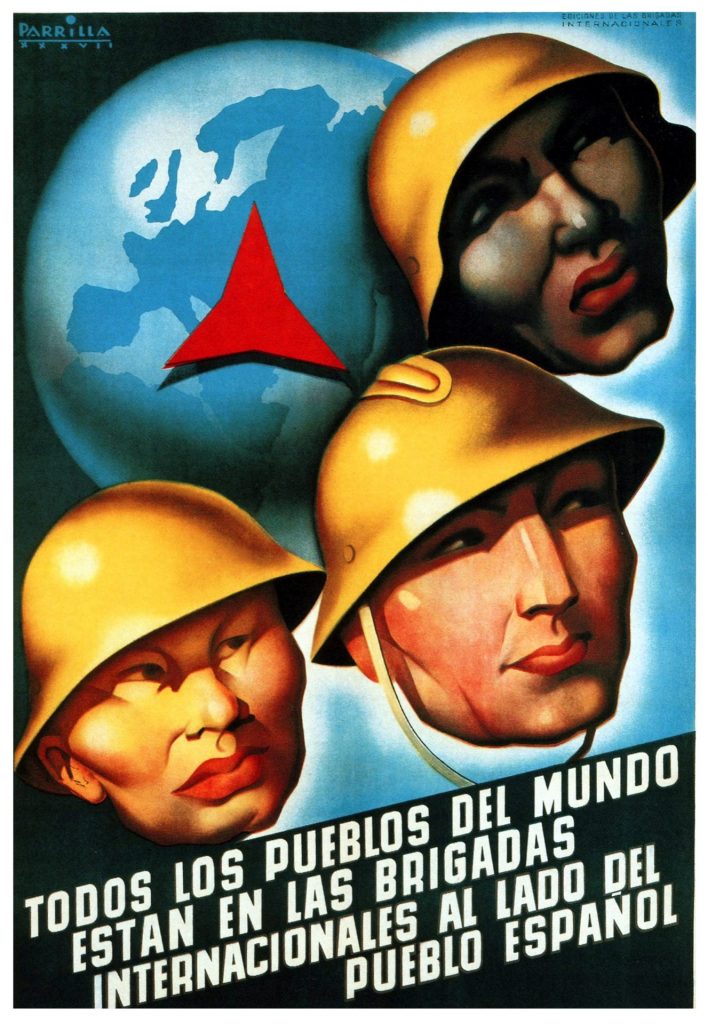

There are decided echoes of Spain’s international brigades. They ran for two years and saw an estimated 40,000 ideologically driven volunteers rotate through muddy trenches redolent of, as Orwell said, “the characteristic smell of war… excrement and decaying food”.

But then volunteerism on battlefields far from home, for a foreign cause perceived to be just and glorious, has a long tradition. Byron died in Missolonghi in 1824, having contracted a fever while fighting to free Greece from the Ottoman empire. He had spent thousands of pounds of his own money on the endeavour.

The Lafayette Escadrille, a group of American volunteers, were in the French skies flying planes against Germany in the first world war, long before America abandoned its position of neutrality. By 1915, when the Escadrille was formed, several Americans had already distinguished themselves in the French Foreign Legion and dozens were volunteer ambulance drivers in France. But it was the Escadrille’s role as an elite pursuit squadron, precursor to the fighter squadron, that attracted considerable international attention to the cause, so much so that a larger outfit – the Lafayette Flying Corps – had to be created to accommodate all the Americans newly clamouring to volunteer.

The Eagle Squadrons that flew for Britain in the second world war saw the same sort of engaged volunteerism on the part of thousands of American pilots. In so doing, they had to sidestep US law, which deemed it illegal for citizens to join the armed forces of foreign nations.

Legality remains a persistent issue when it comes to volunteer fighters signing up for distant wars. Australia has already warned its citizens against flying to Ukraine because signing up to fight for a foreign government may be a breach of the country’s Foreign Incursions and Recruitment Act. British citizens, too, could fall foul of the Foreign Enlistment Act of 1870, which makes it an offence to fight for a foreign power at war with a state with which the UK is technically at peace.

Add to that the explicit warnings set out in Article 6 of Hague Convention V of 1907, one of the first international treaties on the conduct of war, which forbids the forming of corps of combatants or the opening of recruiting agencies “on the territory of a neutral power to assist the belligerents”. In other words, a neutral government should not be exhorting or assisting the formation of a volunteer corps.

The Lafayette Escadrille nearly fell foul of that prohibition a year after its 1915 formation, when the German ambassador to the United States protested that communiques contained allusions to an “American Escadrille” and that the squadron’s planes bore the insignia of a Sioux Indian in full warpaint and feathers.

With respect to Ukraine, then, the British foreign secretary’s full-throated endorsement of potential volunteer efforts to help fight the war against Russia could be seen as problematic.

That said, as legal scholars point out, neutral governments have often sponsored battlefield volunteerism. Before the Hague Convention there was the 1876 mass recruitment of Russians for the Serbian army, which occurred with the formal approval of the Russian government. And in the 1830s Lord Palmerston authorised a volunteer military force, the British Auxiliary Legion, to fight the Carlists, who wanted Spain to return to a traditional monarchy.

The fight for Ukraine links up – in ideological terms – with that 1830s battle against the Carlists and the 1930s struggle against Franco’s Nationalists. All three are for a politically progressive cause, one that inspires the volunteer fighter and makes even extreme hardship bearable.

Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls tells the story of American explosives specialist Robert Jordan, who serves in a guerrilla unit fighting Franco’s forces and selflessly carries out his orders. He is maimed and embraces death so that his comrades and young lover can save themselves.

“I have fought for what I believed in for a year now,” Jordan says. “If we win here we will win everywhere. The world is a fine place and worth the fighting for and I hate very much to leave it.”

Orwell describes the multiple travails when he starts out from the Lenin Barracks in Barcelona. Militiamen, he wrote, “the defenders of the Republic [were a] mob of ragged children carrying worn-out rifles which they did not know how to use”. They wore “multiform” rather than uniform and were woefully light on food, weapons and training. When Orwell was issued with a weapon, it was “a German Mauser dated 1896, more than forty years old!”. Outdated weapons may not be a problem for volunteers in Ukraine, though the hardships of war will be the same.

In A Moment of War, Laurie Lee’s autobiographical account of his time in Spain as a Republican volunteer fighter, the training is described – they drill with wooden sticks and hurl bottles at a pram for anti-tank practice.

But despite all that and despite the disillusionment that would follow, Orwell would later write of his time in Spain: “Curiously enough, the whole experience has left me with not less but more belief in the decency of human beings… The International Brigade is in some sense fighting for all of us – a thin line of suffering and often ill-armed human beings standing between barbarism and at least comparative decency.”

Ukraine presents much the same situation today.