A few months into the pandemic, in the summer of 2020, I watched my children play a video game. It was Animal Crossing: New Horizons, the hugely popular Nintendo title that captivated fans with its cute graphics and immersive social gameplay. In it, players worldwide can go online and converge in a shared digital space: to mingle, to eyeball one another’s creations (each player is tasked with developing an empty island) and to simply coexist.

As the world was gripped by the pandemic and our social tethers began to fray, the game offered a panacea of sorts. For my children it provided a virtual space for them to be with their friends.

For me, it was an awakening.

Here, in this digital landscape fashioned by creative vision and coding, I encountered what many would now call the metaverse. It was a seismic shift in reality, both in what I perceived it to be and what I perceived it could be.

I believe artists have the capacity to help expand this cognitive field. We work in a discipline that constantly pushes us to reconsider and redefine our own personal reality: through fantasy and irony, humour and whimsy, commentary and subtext. In the metaverse, the inherent duality between reality and fiction dissolves, creating a hyperreal existence that is buoyed by technology but fuelled by the imagination we bring to it.

The promise of this hyperreality has both invigorated and infused my work. I have moved into creating NFT art, betting on the idea that non-fungible tokens – mere data, bereft of any kind of tactile, corporeal form – represent an exciting new cognitive realm. I have been focusing on conceptual work that seeks to bring authenticity to the metaverse and the digital spaces we now occupy.

Last year I collaborated with the virtual fashion brand RTFKT Studios on an NFT project called the “Clone X” collection, contributing my artwork for their digitally rendered 3D characters, or avatars. In the spring I launched my long-gestating Murakami. Flowers project, a collection of NFT artwork comprising pixelised versions of my flower artwork.

The impact that this burgeoning digital world is having on my art has prompted me to reevaluate my own personal reality, reminding me of two occasions in my life when the reality of my existing values collapsed.

The first one involves an early encounter with contemporary art. The second involves something far more pedestrian – a sip of coffee.

It was December 1988, and I was visiting New York City for the first time. At the Sonnabend Gallery in SoHo, I was captivated by several large porcelain pieces. One depicted a gilded, white-skinned Michael Jackson clutching his beloved chimpanzee, Bubbles. Another portrayed the cartoon character Pink Panther festooned on the shoulder of a woman modelled after the actress Jayne Mansfield, bare-chested and grinning.

They were works by the artist Jeff Koons. The show was called Banality.

At the time, I didn’t know it was Mr Koons’s show; in fact, I couldn’t even read English. But I remember thinking, “Wow, in America people enjoy buying porcelain in such poor taste for a ton of money. I don’t understand art at all!”

Later I would read in an art magazine that Banality was seen as a cutting-edge exhibition that embodied what some critics called simulationism – a kind of hyperreality in itself.

In light of that, when I looked anew at the sculpture of Michael Jackson, my initial reaction to it was transformed. I felt that I understood it: its manipulation of reality, its subversion of the familiar, its insouciance towards what we held to be true. My encounter with Mr Koons’s exhibit made me question my own judgement.

As for that sip of coffee?

It happened about a decade ago in Japan. The Norwegian coffee brand Fuglen had opened a cafe in Tokyo, and I’d heard rumours that the coffee was delicious. I went to have a cup.

The barista at the counter looked me over. “You are Takashi Murakami, the artist, right?” he asked. “Is there any particular type of coffee you’d like?”

I asked for a cappuccino.

He brought me one a few minutes later, and I took a sip. I almost spat it out. “Excuse me, did you put orange juice in here?” I asked.

The barista grinned. “Murakami-san, as expected, you are quite sensitive,” he said. “That’s totally right, because coffee beans are actually fruits. I bet what you have been drinking to this day is the Japanese-style, extremely dark roast coffee. It is a dark roast because the beans are old. Fresh coffee is fruit. Would you try another sip with this in mind?”

So, I drank again. Then and there, my consciousness click-clacked and restructured itself. I have never had such delicious coffee, I remember thinking.

In both experiences, my brain was tricked. My beliefs were challenged. My paradigms shifted. There is no way to know whether my initial impressions were the product of ignorance, or whether the knowledge I gained led me to truth. But perhaps the ultimate purpose of both of those moments was not to arrive at clear-cut answers. Instead, the purpose was to ask questions – and to reconsider my tenets. That is, to recognise the unknowability of something is, in itself, a reality and a truth. I knew I had been awakened.

It is the same kind of awakening I now contend with as I delve into this new digital universe that melds technology with art, humanity with algorithm, data with substance. My hope is to craft a worldview that fuses the contemporary art world – the sphere that I have until now inhabited – with the digital world. Just as art has always impelled us to expand and reframe our constructs, so too does this new technological terrain. Amid bytes and blockchains, it allows the work of artists to take new forms, exist in new spaces and create new worlds. That is the future we paint.

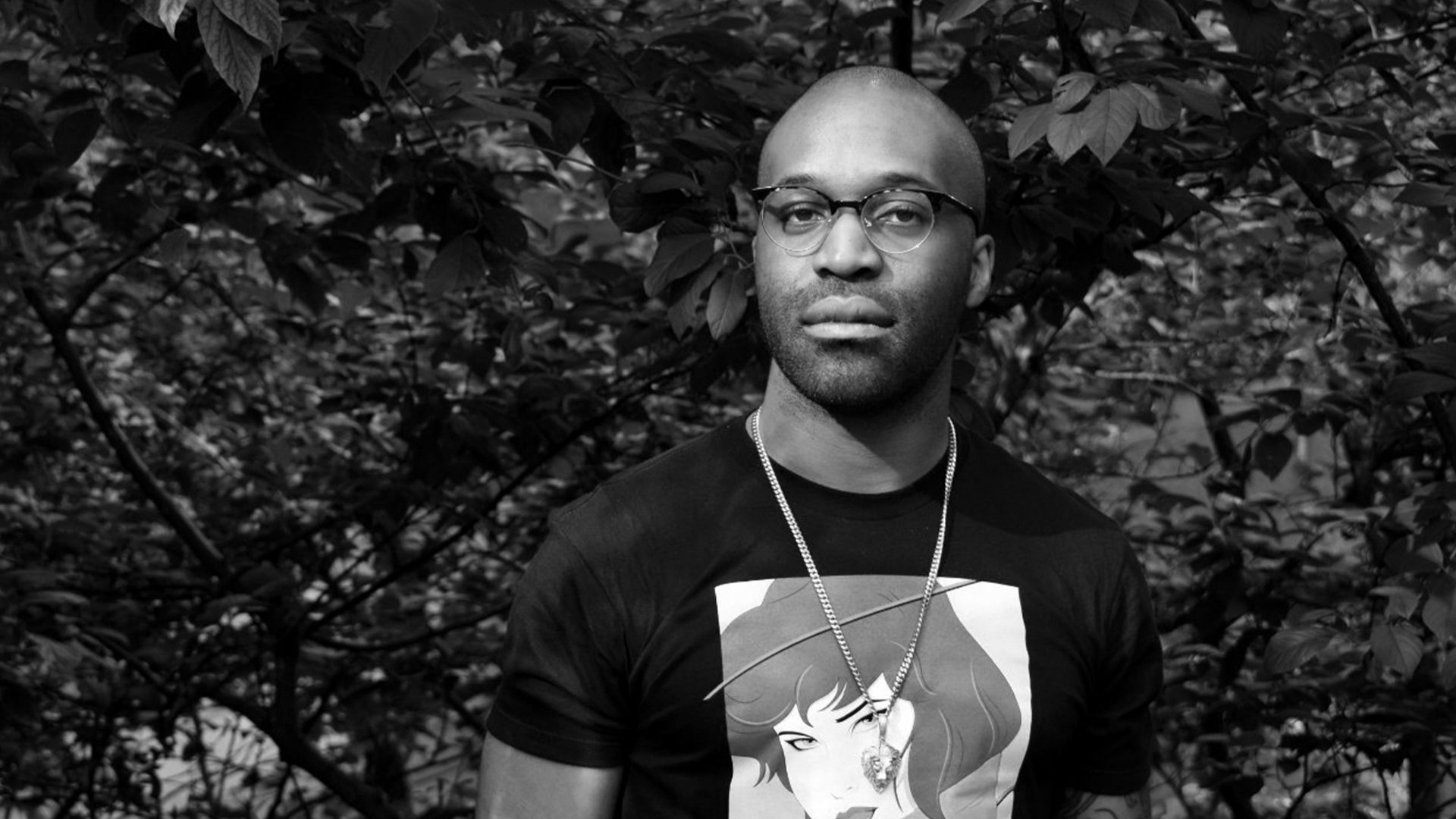

Takashi Murakami is a Japanese artist known for blurring the boundary between fine and commercial art © The New York Times Company and Takashi Murakami