Chin down, eyes wide, cheeks in, lips out, shoulder cocked … the selfie pose is as practised as it is preposterous. Everyone has a favoured expression for the camera, consciously or not, but what of those who have sat for portraitists?

How much control over their image did they have?

At the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, itself the home of many great portraits, an exhibition draws on the collections of around 50 other galleries to illustrate the enduring fascination with self-image.

The wealthy, the aspirational, the ordinary, the extraordinary…. men and women from a wide range of backgrounds, are represented in the 100 or so paintings and drawings which show that it is not merely the well-connected who have been immortalised by those with a gift for capturing a likeness.

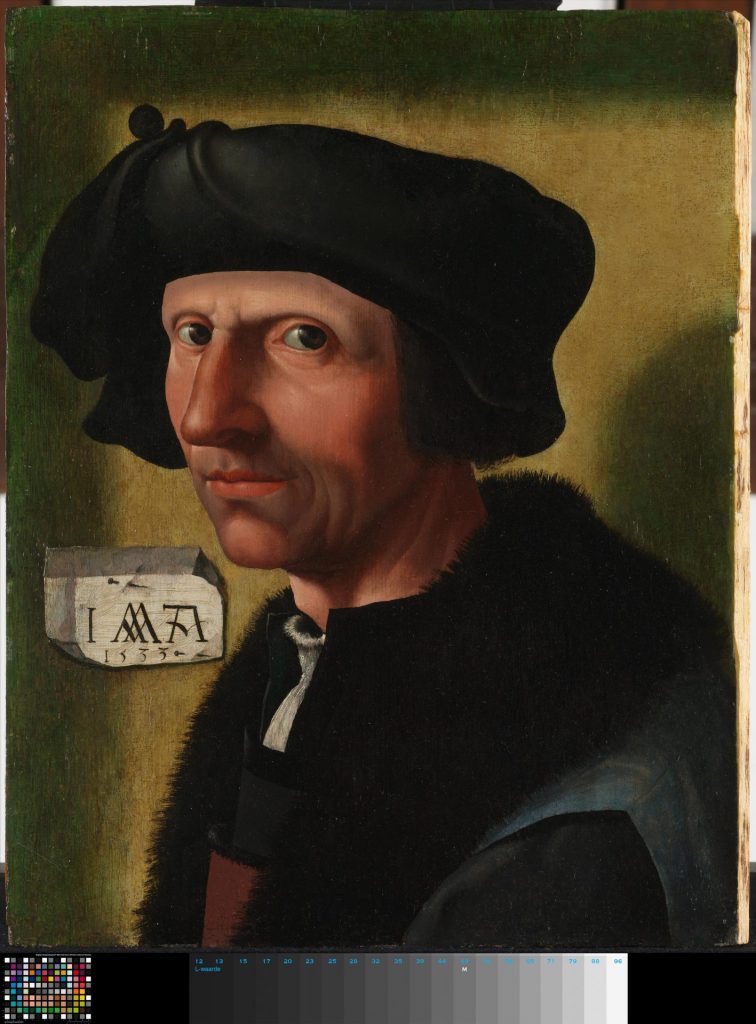

Entitled Remember Me, the show opens with a work that demonstrates the complexity of the portraitist’s task. Dirck Jacobsz (1497-1567), in a double portrait from 1533 loaned by Toledo, shows his artist father Jacob Cornelisz, probably painted soon after the subject’s death.

Cornelisz is shown painting a portrait of his wife, Anna. A self-portrait by Cornelisz was probably a reference point, with oddly lash-less eyes, unimproved upon.

The heavy lids of a fair-skinned young woman gaze out with a comparable directness in Petrus Christus’s Portrait of a Young Girl (1470), one of many examples of ideals of beauty that change with time and geography. The painting was possibly once owned by Lorenzo de’ Medici and may depict Ginevra de’ Benci.

If so, the contrasting portraits illustrate the way in which a single subject can be depicted with marked differences by an artist from the north, and one from Italy. Petrus Christus elongates his subject, and renders the fur of her deep v-necked gown with such precision that it can be identified as the pelt of a weasel. Leonardo da Vinci’s version of Ginevra is round-faced.

Both portraits favour the threequarter profile as the most expressive pose, Italian artists adopting this Flemish pose towards the end of the 15th century in place of the less expressive and communicative full profile.

While beauty was an important attribute for many women in securing an advantageous marriage, and some portraits were commissioned to enable such a match, women’s talent and intellect are also celebrated.

In Jan Sanders van Hemessen’s Double Portrait of a Man and his Wife Playing Backgammon (1532), the woman glances with amusement at the defeated expression of her husband as she trounces him at the board game.

Sofonisba Anguissola needed no man to capture her likeness. A highly successful and sought-after artist in her own right, in her self-portrait she includes the refined religious piece on which she is working. Born in 1535 to a noble family of limited means in Cremona, Anguissola was admitted to the Spanish court, whose figures she painted, as well as giving art lessons to Elizabeth of Valois, the third wife of Philip II.

Painting was considered a more refined occupation than the grafting and crafting of sculpture, and that sense of respectable labour extended to the merchant class too.

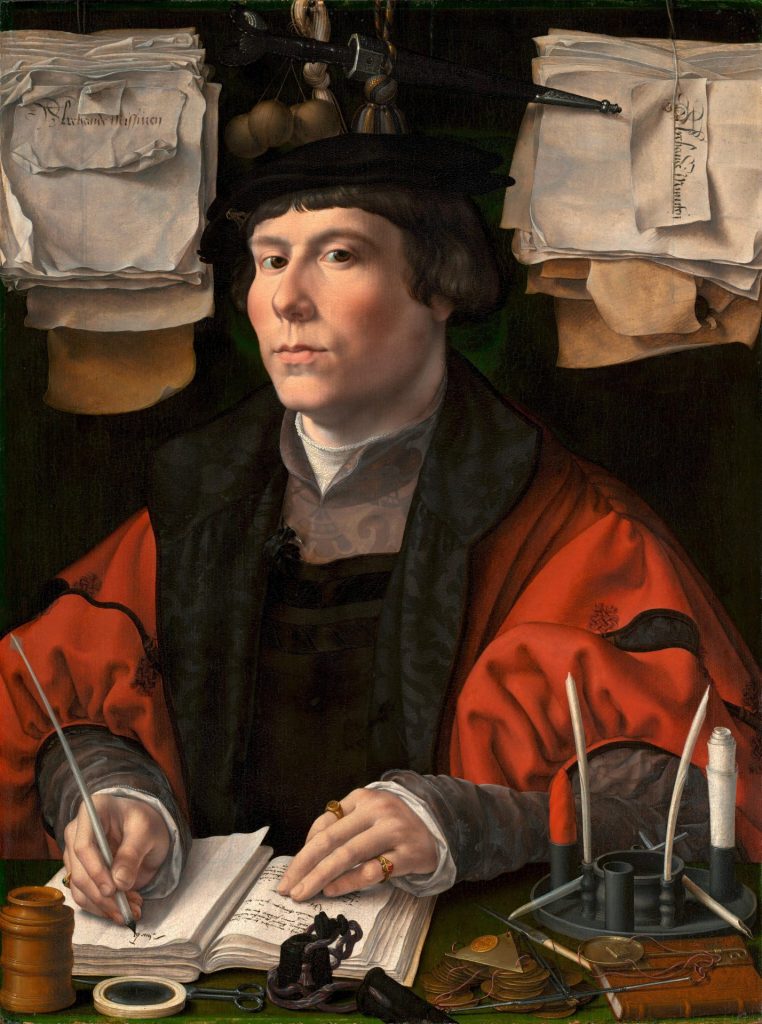

Those who were successful enough to commission portraits show the tools of their trade, proud source of income beyond mere inherited wealth. While not stooping to the indignity of showing their wares, their elaborate paperwork is on view for all to see, indicating the complexity of their transactions.

The subject of Jan Gossaert’s vocational portrait Jon Jacobsz Snoeck is, in around 1530, writing in his ledger, and clues to his background are scattered throughout the picture.

Snoeck’s motto In Acquis Strenuus (Brave in Water) is rendered as IAS on his beret, and plays on the fishy connotation of his surname – snoek means pike.

Piero di Cosimo’s portraits of the important Renaissance architect Giuliano da Sangallo and of his architect father, Francesco Giamberti show Giuliano with the calipers of his profession, while Francesco, who was also a musician, has sheet music. The father’s bent ear is attributed to the distorting binding of his face for the death mask on which the portrait would have been based. The full profile of the father and the three-quarter profile of the son illustrate vividly the Italian artist’s rapid transition from one format to the other.

Not all occupations are so genteel. In one of the earliest surviving depictions in Western art of a black man, dating from the 1520s or 1530s, Jan Mostaert’s subject is, we can assume, a soldier. his black cloak is simple and there is no overgarment disguising the ties that lash his hose to his doublet, although this is in lush crimson velvet. His gloved right hand grasps his sword, and he has been tentatively identified as Christophle le More, an archer in the bodyguard of Charles V.

The badge on his cap records his visit to a Christian pilgrimage site near Brussels.

Earlier still is an acutely observed portrait by Albrecht Dürer, on loan from the Albertina in Vienna, Portrait of an African Man (1508). It similarly defies the stereotypical image of a black subject as seen in representations of the Magi, king Balthazar commonly a somewhat generic figure.

We may smile at the selfie which will one day embarrass its subject – or be deleted – but also regret the passing of the family photo album. The painted portrait is the most enduring record, and often carries with it its intimations of mortality.

Among the common props and symbols are memento mori, reminders that the portrait will long outlive its subject – skulls, sombre texts and flowers that will soon lose their petals.

Death was never far away in the 15th and 16th centuries, but children came thick and fast, little men and women dressed in their parents’ own image. Some bear heavy responsibilities, the oversized cloak on the slender shoulders of Titian’s adolescent Ranuccio Farnese, for example, symbolising the weight of his duties as prior of the Maltese Order in Venice.

But others have a childhood to enjoy. Anguissola captured her sisters Lucia, Minerva and Europa laughing in The Chess Game (1555). It’s a rare moment of levity in an art form that, like those vamped-up selfies, has proved to be a pretty serious business.

Remember Me runs at the Rijkmuseum, Amsterdam, until January 16, 2022.