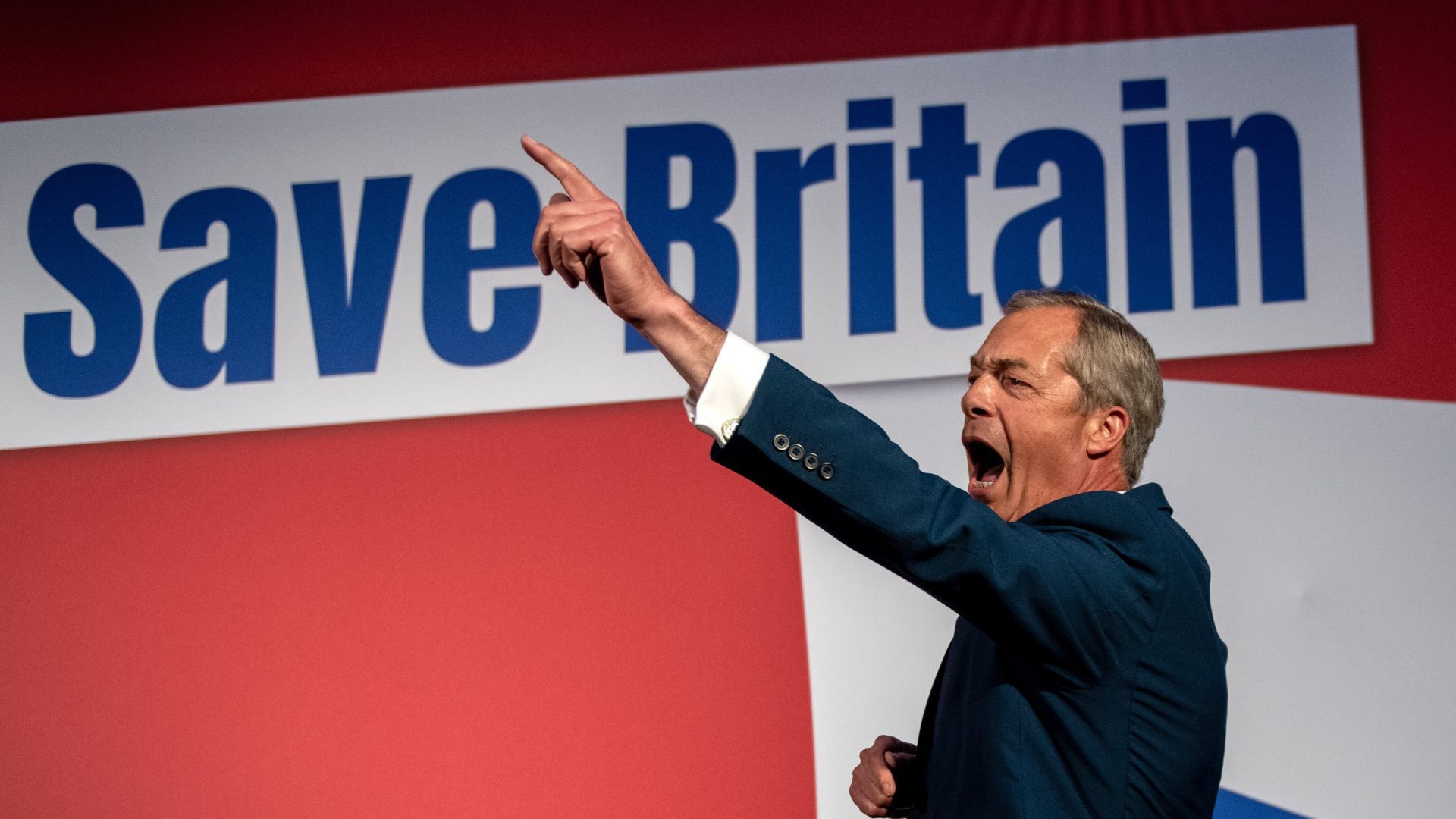

It’s finally happened: Reform is in first place in the polls – or to be more precise, in one poll. Nigel Farage’s most recent political vehicle (remember UKIP? Or the Brexit Party?) has hit 25% in YouGov’s most recent tracker, with Labour in second on 24% and the Conservatives on 21%.

Predictably, reactions as to what this means vary wildly according to the politics of the observer. All everyone can agree on is that is backs up their own previous convictions.

Reform supporters take it as proof of their inevitable rise, while Labour’s detractors on the left see it as proof of Keir Starmer’s total failure. Labour and Conservative loyalists, meanwhile, emphasise that it is “only one poll”.

To an extent, all of them are right. Reform is, so far, only ahead in a single major poll and than lead is well within the margin of error. More significantly, it’s also several years until a general election and there is plenty of time for things to change.

So a lead for Farage’s party right now is essentially a vote for “none of the above”, and at this time of dissatisfaction with the two major parties, perhaps isn’t a surprise.

But Reform’s performance in the poll has been consistently rising over time, and this should not be ignored. The party finished third in vote share in last year’s election and has since risen steadily, overtaking the Conservatives to claim second place and now challenging Labour for first.

The combined popularity of Labour and the Tories is nearing its all-time lows – between them, the two big parties currently have a combined vote share of less than 50%. As recently as the 2017 general election, they commanded more than 80% of the national vote share.

If the vote stays as fragmented as it is, and they stay as unpopular as they are, the UK’s politics will remain volatile and unpredictable, perhaps more to the advantage of Farage than ‘traditional’ smaller parties like the Liberal Democrats and Greens.

Some commentators on the right are focusing on the combined vote share of two different parties, though – of the Conservatives and Reform, which stands at 46%. Labour is languishing on 24%, they note, meaning that if the two parties of the right joined forces, they would have a commanding victory.

This is the reasoning of the “progressive alliance” or “rainbow coalition” in reverse – and will likely fail as badly for the right as it did for the left. Many Liberal Democrat voters would not vote Labour – it is part of why the party exists, and why its heartland seats are those it takes from the Conservatives in southern England. Many Green voters opt for the party because they are disillusioned with or disgusted by Labour. If the three parties joined forces, they would lose a significant fraction of their voters.

All of this is even more true for Reform and the Conservatives. Reform is trying to run a populist agenda that doesn’t neatly fall into conventional left/right categorisation on economic issues. A huge part of its current success is fuelled by anger at the last Conservative government – and while some of its supporters would love a deal with the Tories, others would be disgusted and depart. Voters don’t obediently do what pundits think they should do.

Reform’s growing support means they need to be taken seriously as a political force in the UK – at least for now. But history tends to suggest that they are still an extremely long way from guaranteeing a breakthrough that could make them a viable party of government.

UKIP managed to go one better than coming first in polls – it came first in a national election, albeit to the European parliament, in 2014. The single-issue party then withered and all but died within a couple of years once the referendum took their single issue away.

In the early 1980s, the SDP – a breakaway party from Labour under Michael Foot – hit 50% in the polls, winning by-election after by-election, only to then secure a meagre 23 seats (a total shared with the liberal party) at the 1983 general election. The British political system is much better at producing parties that seem to threaten the existing order than ones which actually do it.

The rise of Reform in the polls isn’t a nothingburger. It’s worth some attention, but it also doesn’t suggest any need for radical action or a change in direction, especially for Labour. If the government can deliver on voters’ priorities and recover its popularity, Reform will diminish. If it can’t, then Labour is screwed come what may.

As the party in government, Labour’s fate is in its own hands. The same, though, cannot be said for the Conservatives.

Kemi Badenoch has been given almost no time to learn on the job, given the pressure she faces from an insurgent Reform on her right – but unless she finds some answer to it, and soon, her leadership may collapse even faster than her party’s vote share.