Thirty years ago this weekend, Wales’s greatest rock export – and the most

political band in Britain – took to the stage for their maiden Reading festival

performance and set themselves completely apart from every other act on the bill.

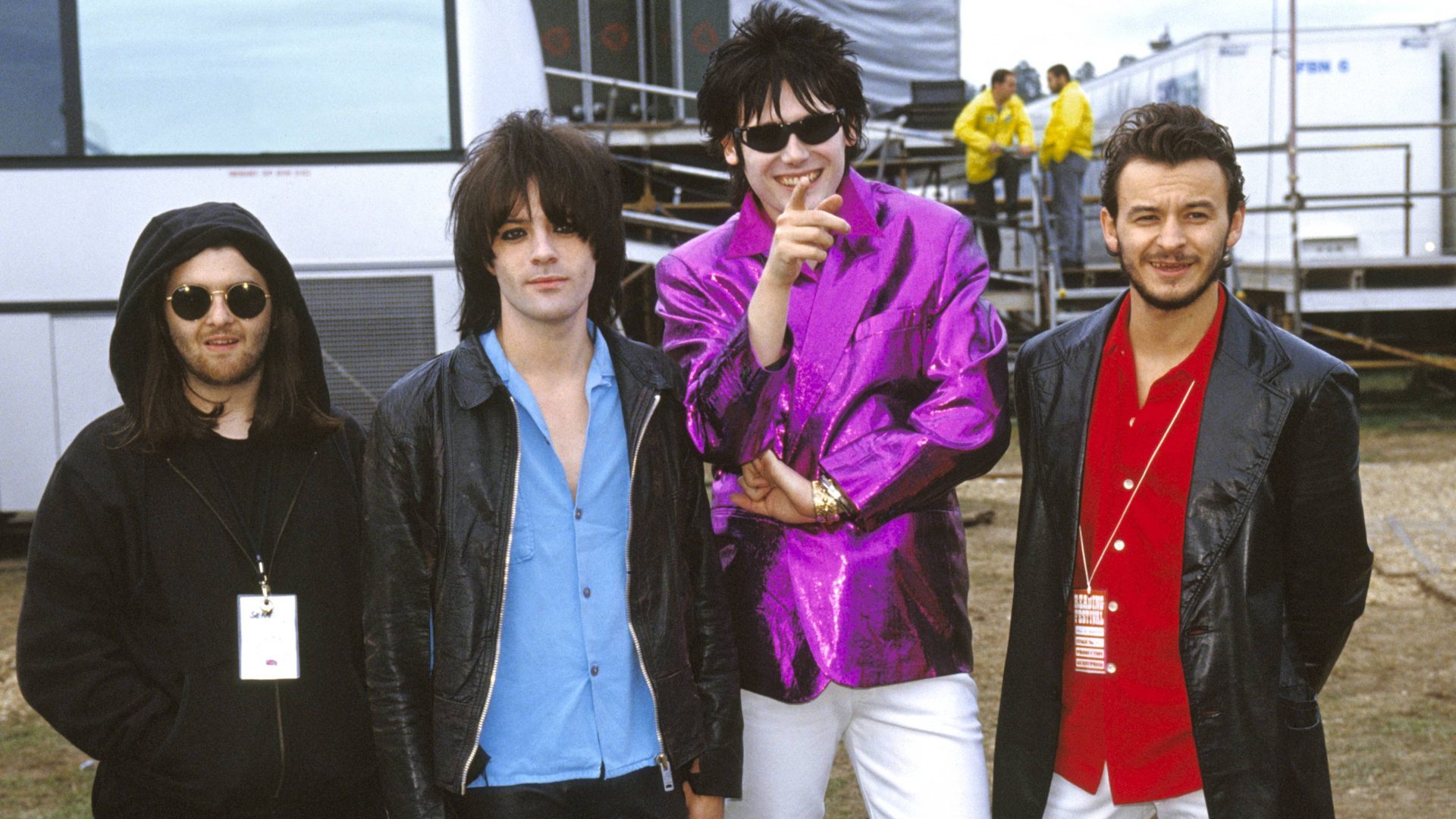

The Manic Street Preachers – four working-class twentysomethings from the south Wales valleys – had released their debut album, the deliberately overblown Generation Terrorists, earlier that year, and Reading was their biggest gig yet. It was a significant year for the festival itself too – Sunday’s headliner was Nirvana, who played what would turn out to be their last British gig. The Manics’ set is hardly as memorialised, but it found them displaying all the qualities that were quickly making them loved and hated in equal measure.

Always overtly concerned with the visuals, they were strikingly different from the jeans and T-shirt-wearing grunge and baggy bands playing that

weekend. Virtuoso guitarist and powerhouse vocalist James Dean Bradfield was bare-chested and oozing aggression, 6ft 3in bass player Nicky Wire was resplendent in puce lamé and a feather boa, and lyricist and spiritual heart of the band Richey Edwards was channelling New York punk, with a Ramones haircut and bashing away at a guitar that, in his untutored hands, was primarily a fashion accessory.

And the hostility, contrarianism and incendiary political comment that had

made them grist to the mill of the music papers was fully apparent, their self-conscious intelligence contrasting with the wasterism and hedonism in

evidence elsewhere. Manics T-shirts bearing the words “Reading 1992, Cultural Chernobyl” indicated the vitriol they had for their music scene

contemporaries and the set list was a relentless onslaught of lyrical radicalism and punk aggression, beginning with the searing You Love Us, their ultimate statement as media-baiting controversialists.

“You love us like a Holocaust,” Bradfield snarled on that opening song, and the sentiments of the rest of the singles from Generation Terrorists, which made up the bulk of their Reading set, couldn’t have been less pop-friendly either. Yet, with Edwards’ and Wire’s stream-of-consciousness lyrics backed by the impeccable rock confections of Bradfield and drummer Sean Moore,

their year was punctuated with chart success, with a Top 30, three Top 20s, and a Top 10 single.

And where there are chart hits, an invitation from Top of the Pops soon follows, a milestone that was an express ambition of a band who said,

with performative arrogance, that they would sell 16 million copies of

Generation Terrorists then split up. While Wire had told the NME earlier

that year: “We’re going to set fire to ourselves on Top of The Pops,” they

didn’t go quite that far, but you only had to look at the bewildered reaction

of the audience to James Dean Bradfield in skin-tight white jeans, and with “You love us” scrawled on his chest in lipstick to see they had not exactly ingratiated themselves when they made their appearance in February.

But, for such a political band, 1992 was important for other reasons too. Neil Kinnock’s defeat in April’s general election was personally felt since the band lived in Kinnock’s constituency of Bedwellty. They had grown up amid the tearing of the social fabric wrought by the miners’ strike and saw “harnessing working-class rage” as their mission. As the Tories claimed a

fourth consecutive win, the sense of hope ebbing away was palpable.

The Manics quickly moved into a new era, 1993’s Gold Against the Soul followed by the pièce de résistance LP The Holy Bible, built around Edwards’

lyrics about prostitution, anorexia, self-harm, the Holocaust and serial killers. When they played Reading again two years later, he was in rehab and the following February he disappeared on the eve of flying to the US for a promotional tour, never to be found. Things had got very dark very quickly, and suddenly so much about 1992 seemed like youthful idiocy. But the posturing had always been underpinned with a genuine anger rooted in the experience of inequality and an appreciation of how the individual is affected by the society they live in.

“Our voices are for real”, Bradfield sang on You Love Us. Under the lamé and lipstick, they really were.

MANIC STREET PREACHERS in five songs

Motorcycle Emptiness (1992)

Commenting on consumer culture (“From feudal serf to spender/ This wonderful world of purchase power”), this was the sublime stand-out

moment of Generation Terrorists.

Love’s Sweet Exile/Repeat (1991)

This double A-side demonstrated how Bradfield and Moore’s anthemic rock sugared the pill of Edwards and Wire’s stark lyrics, and it reached No 26.

Slash ’n’ Burn (1992)

Referencing capitalist society and third world exploitation (“Gorgeous poverty of created needs”), this opening song of their debut LP betrayed the band’s American glam-metal influences.

Suicide is Painless (1992)

A charity cover of the theme from MASH, this was as lyrically nihilistic as anything the band wrote themselves. It would be their biggest hit until 1996’s A Design For Life.

Little Baby Nothing (1992)

Rounding off 1992, this reflection on the sexual exploitation of women, with

additional vocals from former porn star Traci Lords, also made it into the Top 30 due to its anthemic brilliance.