For the first time, a film told mostly in the Irish language is receiving a wide cinema release in the UK. The release of The Quiet Girl (An Cailín Ciúin) is a landmark moment for both Irish cinema and for the language, and could be seen as part of a surge of nationalistic pride that may also include the victories for Sinn Féin in the recent elections.

“I wouldn’t want to make a political point with my film,” says debut feature director Colm Bairéad. “The Irish language is one of a number of many strange things that form part of the Irish psyche but it feels that for the first time, the language is being celebrated nationally, certainly on the big screen at least.”

Bairéad’s film, The Quiet Girl, is making all the noise. It became the first-ever Irish language film to carry off Best Film at the IFTAs (Irish Film and Television Awards) in March, where it saw off the challenge of Kenneth Branagh’s Belfast to clinch a full seven wins out of 10 nominations, including one for Bairéad himself as Best Director.

“It’s rather wonderful to think that this beautiful language is out there, bouncing around in darkened rooms and delighting ears in the UK and also

in theatres around the world,” he says. “For Irish language drama, that’s unprecedented.”

The film’s success is undoubtedly boosted by its source material, Foster, a short story by the Irish writer Claire Keegan that originally appeared in the

New Yorker, and then became a 2010 novella that is now part of the school literature syllabus.

It’s about a nine-year-old girl, Cait, sent to spend a long, hot summer with relatives on a dairy farm in rural Ireland while her impoverished mother gives birth (yet again, another mouth to feed). There, with these new, quasi-foster parents, Cait discovers a new way of living, with tenderness and love, although dark secrets still lurk.

Full of lyrical passages, the film matches the book for beauty, even if Bairéad, an Irish speaker himself, translated Keegan’s English-language writing into his Irish language screenplay. The film is part of an initiative by the Irish broadcaster TG4 and its Cine4 scheme to encourage Irish-language feature films, a fund that has clearly borne fruit, culturally and commercially.

“I read the book and had tears streaming down my face,” he recalls. “And I could just see the images, the visual language. It was so cinematic to me and was something I could transpose easily into the Irish-language setting. It’s a film about silence and language, and the limitations of language to convey true thoughts and feelings, so that was always an interesting aspect of it for

me.”

Irish is an official language, of course. It is used on all road signs and government documents, and it is now compulsory in primary schools again, with some schools using it as the main language, and achieving impressive results. There are certain areas of the country, called Gaeltachts, where it is

the predominant spoken language, although only 100,000 or so really do speak it.

“People tick boxes on the census to say they speak it, but they don’t really,

other than basic school-age Irish,” says Bairéad with a grin. He grew up in a

bilingual house in Dublin, his mother speaking English, his father only Irish.

“I’ve always had a bilingual existence, so it’s not odd for me at all, but I did want that to be part of the layers of the film. It adds meaning and defines two worlds.”

Cait’s home life is tough and poor, her father is a drunk and a womaniser and you can sense violence in him. He only speaks English. Cait and her sisters speak Irish together as a sort of protection, a secret code which their brutish father glowers at.

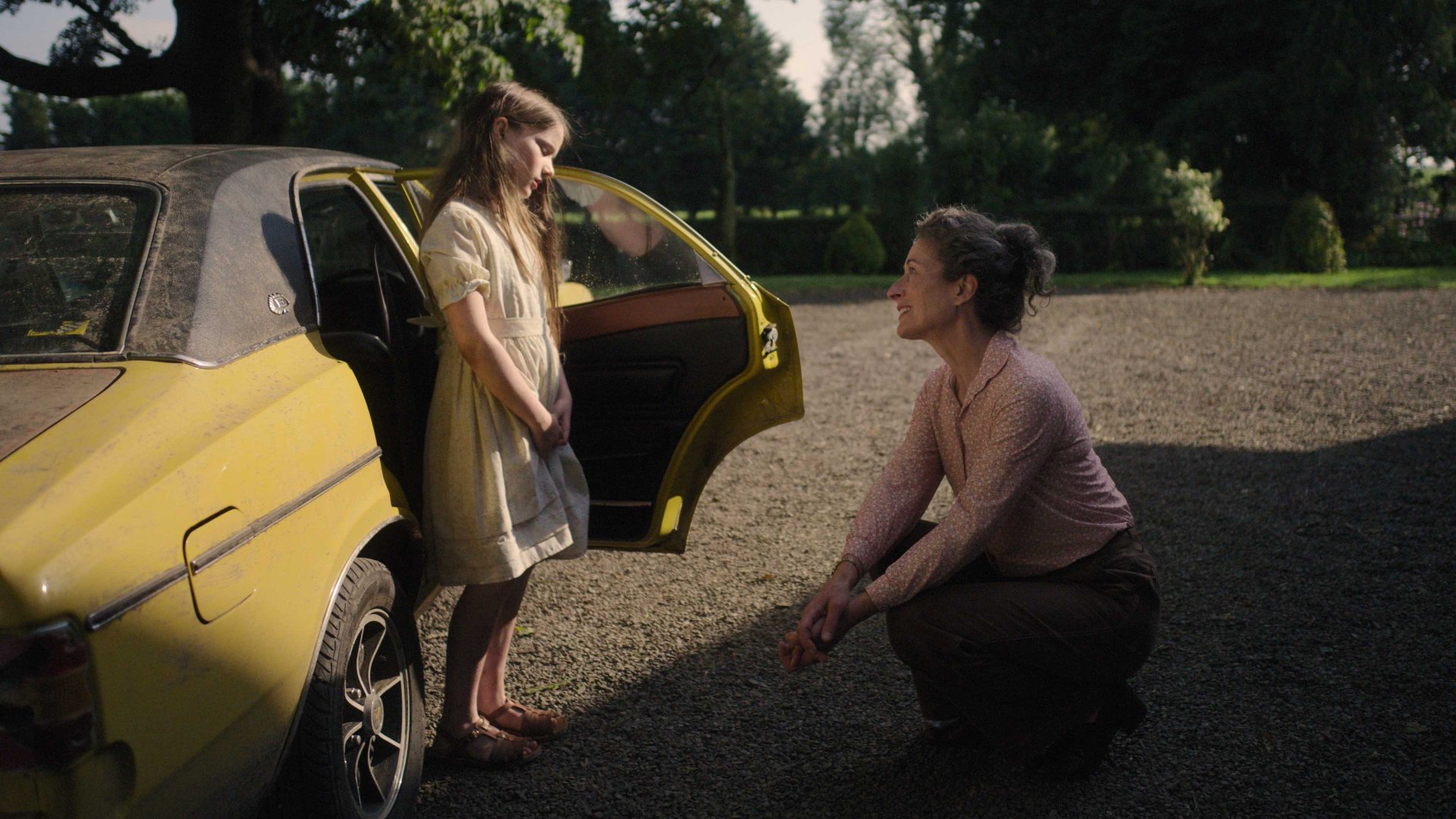

So when she’s sent away to the Kinsellas’ home for the summer, timid, bed-wetting Cait slowly finds softness and kindness. “All you needed was a bit of minding,” says her “foster” mother Eibhlin (played by striking-looking actress Carrie Crowley) brushing the girl’s hair and giving her a hot bath for what looks like the first time. Cait also discovers eating healthy breakfasts and the treat of Ireland’s own Kimberley biscuits that the foster father, Sean (Andrew Bennett), slips her on occasion…

Cait is played by Catherine Clinch, who won Best Actress at the IFTAs and was discovered through the network of Irish-language schools. “You go out into the world to find a diamond in the rough,” says Bairéad, whose wife, Cleona Ní Chrualaoí, produced the film. “We needed an unknown for Cait

and we had to look for only native Irish speakers, for all our actors really. She sent in a self-tape and we just loved her stillness and her face, which just invites the camera in to witness her, there’s no visible acting, which makes the audience sort of lean in to get closer, to pay attention.”

Bairéad says that the pool of Irish-speaking actors is of course small, but that you couldn’t teach it phonetically, that it is vital the language, the dialect, the accents are all genuine. “When I hear Irish being spoken, particularly by kids these days who are going through that school system, I find it incredibly

beautiful,” he admits. “It’s like finding a genius three-year-old playing the violin or something.” Bairéad and his wife have young children and are raising them in an Irish-speaking environment, although they live in Dublin and not one of the designated Gaeltacht areas of Donegal, Mayo, Galway and Kerry, with sections in counties of Cork, Meath (where the film was shot) and Waterford.

The film does use a mix of English and Irish. English is the language of

the media (this is set in 1981), so radio adverts and the television in the

background all hum with English. Irish audiences will get the era references, particularly to a TV quiz show called Quicksilver, with its catchphrase of “Stop the Lights” and its incredibly low amounts of prize

money. So language, sound, silence are a crucial part of the watching experience, as is the landscape, both physical and linguistic, with cinematographer Kate McCulloch capturing the lush green textures of the trees and grasses.

It opens with an extraordinary shot of something buried in the long grass, an image it takes the viewer a while to focus in on – is it an animal, or a dead body, entwined in the wisps of a meadow, or is it even a bit of treasure? It is, of course, Cait, who springs to some kind of life, a visual metaphor for her compartmentalisation, her separateness, her will to hide and be alone and yet to be part of the roots, part of the land.

“I guess there’s an irony in the fact that Cait doesn’t really have many lines in the script,” says Bairéad, laughing. “It’s a film about language and the Irish language in particular, but hers is more a performance from silent cinema. But it is about her coming to life, blossoming and finding a new voice, so it’s a very powerful image to open with.”

The Quiet Girl takes its place among a wave of European films rediscovering minority languages. Bairéad cites recent Berlin-winner Carla Simón’s 2017 feature, Catalan coming-of-age movie Summer 1993, as a huge inspiration, thematically and linguistically.

But there is also Welsh-language horror Feast opening in the UK this summer, and at Cannes in just a few days’ time Bait director Mark Jenkin’s follow-up, Enys Men, will feature Cornish dialogue and a specially composed song in Cornish, perhaps the first time that language has ever been showcased on the Croisette.

And only last week, I saw the new restoration of Joan Micklin Silver’s 1970s black and white American indie film Hester Street, a film set in early 20th-century New York’s Lower East Side that predominantly uses Yiddish as its language.

“We’re going toe-to-toe with the rest of world cinema,” says Bairéad proudly. “It’s amazing to be part of all these international film festivals, so it does feel like a watershed moment. I’m thrilled people are getting to hear it, in Ireland, where it’s kind of becoming a selling point for the movie, as much as anywhere else.”

Of course, it helps that the film is excellent, beautiful and powerful as well as other-worldly in some of its images and sounds. You can have a film that’s not great and the dialogue won’t help it whatever language it’s in. But it’s certainly wonderful to hear Irish spoken at such length in the film and sounding so haunting in its musicality.

To my untrained ear, in The Quiet Girl, it sounded more like a Norse language, and watching it I was reminded of Icelandic films and Norwegian dramas as much as anything else.

And you think, why not? There’s no reason why language ever needs to be

a barrier in cinema – audiences are more used to subtitles than ever now,

and through cinema language can be celebrated and understood. It’s a key

factor in identity, which is something all filmmakers and storytellers are

concerned with. The Quiet Girl is loudly banging the drum for Irish film, and Irish itself.