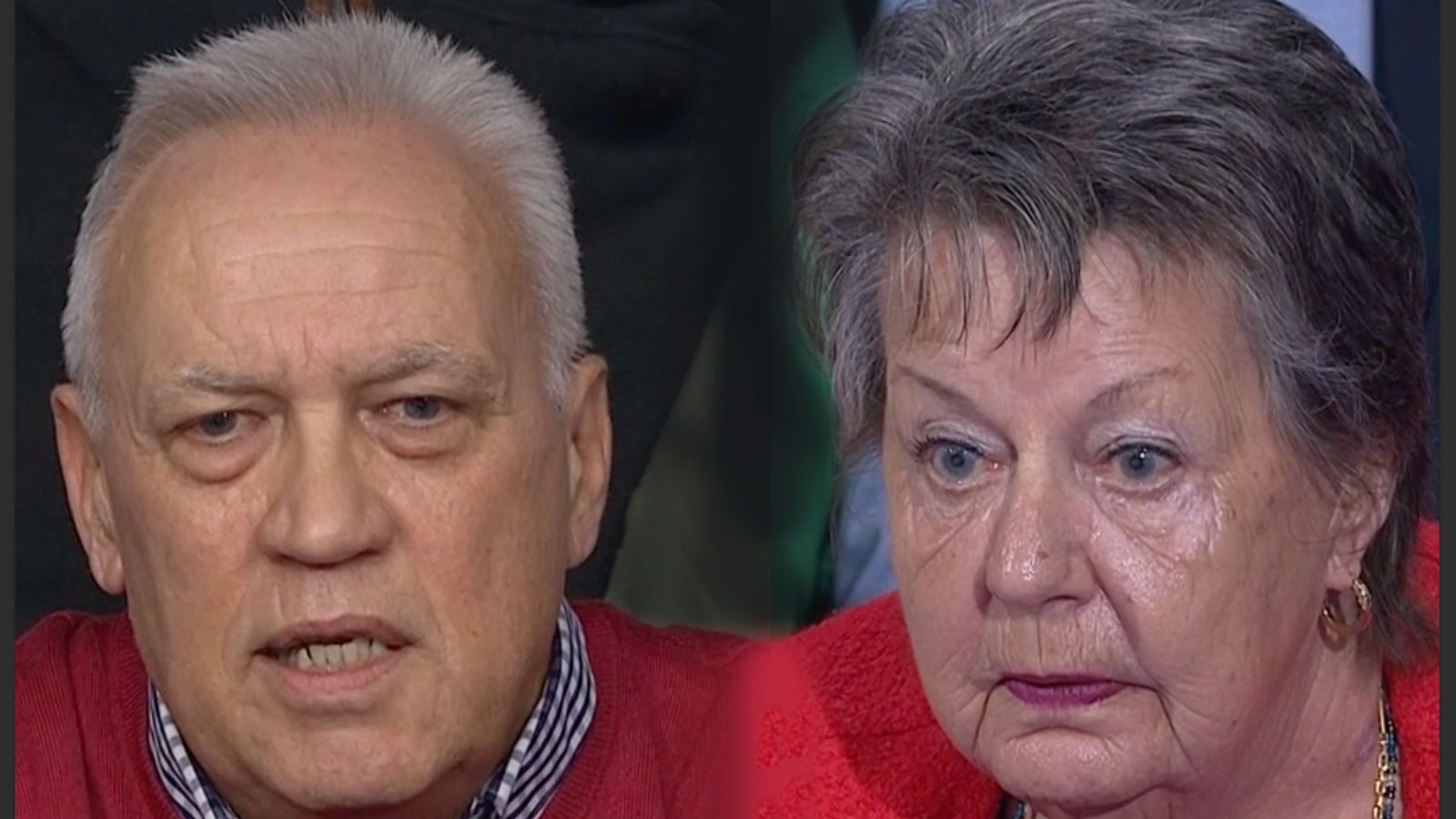

Last night’s BBC Question Time squaring-off between Alastair Campbell and Nigel Farage turned out, instead, to be a battle between one red jumper and one red jacket.

The red jacket belonged to a woman, a pensioner, whose view of immigration dove-tailed neatly with Farage’s narrative; dismissive, ignorant and bigoted.

“I don’t believe in any asylum.” Nor did she pity the refugees fleeing conflict and persecution. “Too much is made of it,” she said.

“I feel very sorry for the little towns, the little villages where these people have been put, where people have lived all their lives, and they are frightened.”

Farage agreed. “We’ve always taken refugees. But what’s happening now… [they] are not genuine refugees.”

The red jumper belonged to a man, grey-haired, probably mid-60s, who had recently visited the National Holocaust Museum in Nottinghamshire.

In 1930s Germany the populists blamed the Jews, he said. In Britain today, the populists blame the immigrants.

“But the immigrants weren’t responsible for austerity. The immigrants weren’t responsible for Brexit. The immigrants weren’t responsible for Liz Truss.”

The end product of the demonisation of Jews in Germany, the man in the red jumper warned, was Hitler and all that followed. “The future of that path is very, very bleak.” A conspicuously loud round of applause followed, led by Alastair Campbell on the QT bench.

The battle of the red attire is the battle that’s coming our way in the next general election. In 2029, the choice will be between pretending we can isolate ourselves from the realities of a convulsing world or facing into them with an inspiring plan for our place in that world as a positive, progressive influence.

What the next election will not be won on is the fixing of potholes, the building of 1.5million houses, or Britain’s economic ranking in the G7. Even a few extra quid in our pockets won’t swing it. To think so is to misunderstand the depth of feeling that has been allowed, essentially unchallenged, to fester in the hearts of many about how this country is going, has gone, wrong.

Earlier in the day, Keir Starmer gave his Big Speech – which turned out to be a rambling, garbled restating of this government’s strategy for first steps, milestones, missions, goals, and foundations.

As a communications exercise in national leadership, it was ghastly. Starmer is often excused for his delivery because he is technocratic, lawyerly, Mr Competent. This lets him, and his invisible svengali Morgan McSweeney, off the hook.

Thursday morning’s word-salad wasn’t just lacking in rhetorical power or policy vision (although it seriously lacked both). It betrayed the reality that Starmer has totally misread the nature of the challenge Britain and, much less importantly, his Labour government faces at the next election.

Starmer and McSweeney’s theory that competent delivery of marginally better living standards (because marginal is all anyone could possibly hope for in four years of cash-strapped progress) will subdue the populism of Reform UK is flawed. Recent evidence in the US election, where a much-improved economy did nothing for the Democrats, suggests it does not have the power to out-punch populism.

Farage – with a transatlantic Trumpian wind in his sails and the financial backing of the world’s richest man – believes he can be our next prime minister.

He’s right to believe it. It’s entirely possible, such is the volatility of voting behaviour in modern democracies, combined at this moment in our history with the near-collapse of the Tories.

It’s a chilling prospect, and one that demands a tooth and nail fightback. Technocratic, lawyerly competence are not the leadership qualities to defeat a man like Farage.

Audacity, vision and – as Matthew d’Ancona ventriloquised for him so brilliantly in this week’s New European cover story – brutal candour about the challenges of post-Brexit Britain’s small and lonely place in the world today, are what Starmer has to summon if he is going to prove himself a Labour prime minister worthy of his enormous, and enormously fragile, parliamentary majority.