Writing about the failings of the Home Office can feel like a form of torture in and of itself – being cursed to call out the same casual cruelty, bureaucracy, incompetence and mistake after mistake after mistake, with nothing ever changing.

It’s easy and tempting to focus on whoever is currently saddled with the miserable task of being home secretary, and blame the sclerosis and incompetence on them – that’s how ministerial accountability is supposed to work, after all.

Priti Patel certainly makes giving in to this temptation easy, often pushing across the very worst of her department’s agenda – with institutional cruelty to those seeking refuge very much part of the plan, rather than an accidental side-effect of it. Given that last week Patel said that the lesson of Windrush was showing the need to have good advance documentation of immigrants, there’s plenty to aim at.

But home secretaries come and home secretaries go, and the Home Office carries on much the same. No department – except maybe the Treasury – so successfully captures its ministers and turns them to its own institutional agenda. Home secretaries don’t run the Home Office – it’s the other way around.

To get a sense of why the Home Office is so awful, it’s good to know what it’s like from the inside – and the answer is it’s full of people absolutely terrified that the next big fuck-up will be their fault.

The Home Office manages multiple services that people only notice when something goes wrong – the wrong person gets deported, or the right one doesn’t and goes on to kill or injure someone. Another UK police force has a racism scandal, or corruption, or some other issue. Security services miss something obvious and we suffer a major terrorist attack. When anything goes wrong it can be spectacular.

Given that the services the Home Office manages have been chronically underfunded for more than a decade, things are likelier than ever to go wrong.

In the absence of funding, the Home Office pushes for ever-more powers, no matter how draconian, in a bid to try to do the job more easily with fewer resources – a criminal justice procedure with proper protections for rights costs more than one without, after all.

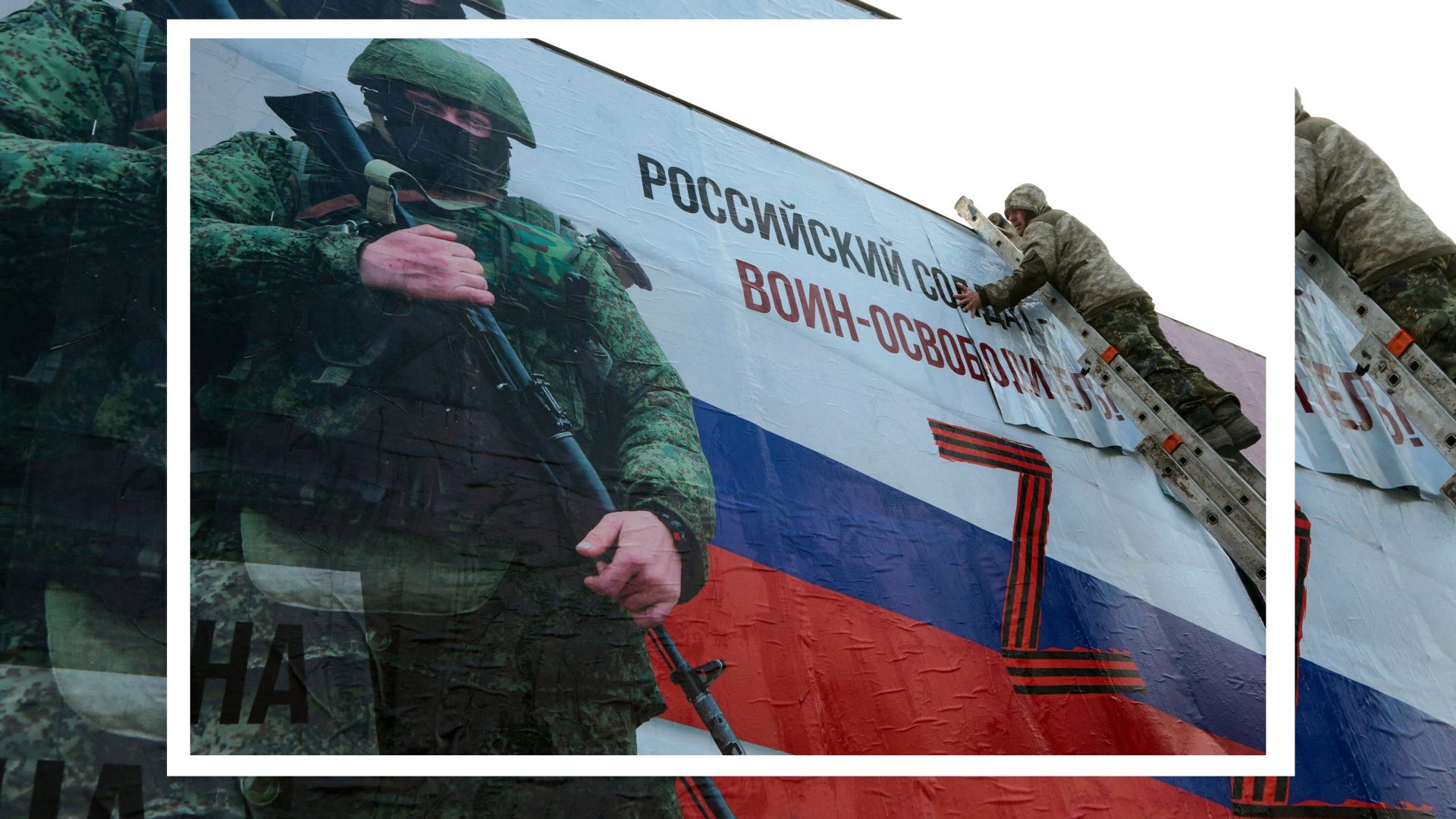

The bunker mentality in the Home Office is so strong that it makes Downfall feel like a holiday camp. When you have this backdrop clearly in your head, the Home Office’s meanspirited and chaotic response to Ukrainian refugees starts to make some sense – at least according to its own internal logic.

Controlling and managing immigration has been the central mantra of the department since at least 2010. Worrying about what people might do if they haven’t been appropriately screened is also one, too – the internal panic will immediately have turned to warnings of what would happen if someone who came from Ukraine engaged in a violent crime. That’s just how the Home Office works.

The obvious suggestion when talking about the serial failings of the Home Office is to talk about scrapping it – but given that there is really no country without some form of interior department, we would do well to ask ourselves where the people in any new body would come from. The same people and the same duties with a new name wouldn’t make anything better.

We could, though, look at rejigging what responsibilities the Home Office has. Why, for example, does the same department that controls the police have to have responsibility for immigration? Because the Home Office sees everything through the lens of national security, it looks at immigrants and refugees through that lens too – that’s how it sees the world. It also does nothing once someone is in the country: integration, housing, etc are all someone else’s problem.

What might UK immigration policy – and attitudes – look like if various other departments managed it? If the health department was in charge, you might see a focus on bringing in health workers, while the education department would probably be pushing policies to bring in teachers.

If the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) had the responsibility, we might have immigration policy through the lens of investors, skilled workers and innovators. If it was run by the same people who run the UK’s international development effort, we might see a joined-up aid and refugee policy.

More radically, you could even run it through something like the Department for Levelling Up and devolve out policy to an extent – some areas are desperate for younger families and workers to move to them, and might be very open to taking both economic migrants and refugees. Others, if they must, could make other choices.

The Home Office exists to see the world through the lens of security. But that’s only one way of looking at things – something that’s easy to forget when it’s often the only way we have ever heard the debate framed. Immigration is no more intrinsic to the Home Office than development is to the new Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), having happily run separately from it for years.

Perhaps being free from the endless rows over immigration could even start the Home Office on a path to becoming less dysfunctional – and maybe even encourage the government to consolidate the criminal justice system back into one department, rather than the current bizarre system where courts and probation fall under one department, while police are managed by another. Right now, criminal justice is in crisis and ministers and departments can just cheerfully pass the buck back and forth.

This is all likely, alas, to be wishful thinking. Patel has swallowed the Home Office playbook entirely, trotting off its nonsense lines that surely only it believes – like the nonsense that the UK was, for example, the first country to set up a visa system especially for Ukrainian refugees. This was technically true, but only because virtually every other relevant country simply dropped visa requirements entirely.

The Home Office is going to carry on as it is until someone stops it. Priti Patel is not the woman for the task.