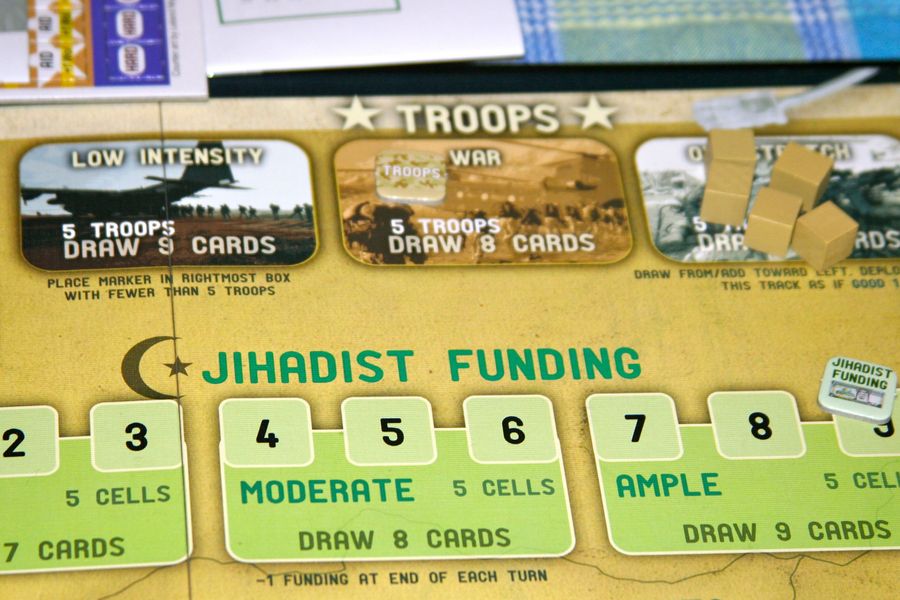

If your only exposure to board games came through childhood Monopoly and Trivial Pursuit, you might be surprised to learn there were games that presaged the recent disaster in Afghanistan. But Volko Ruhnke, the designer of counterinsurgency simulations Labyrinth and A Distant Plain, also happens to be a CIA analyst.

“A thesis in Labyrinth was that if a side tried to change a Muslim regime by force, the other side could exploit that opportunity,” he explains. “Eventually, one side would exhaust itself and go elsewhere.

“Clearly, it was not the Islamic fundamentalists, the Taliban, who became exhausted.”

Labyrinth was published in 2009 and was an early example of a genre that’s only now beginning to find its feet. Prior to Labyrinth, most political board games took politics as window dressing for strategic puzzles, such as 1986’s Die Macher where players competed to win an imaginary election in Germany.

Ruhnke, by contrast, and the designers who came after him, are interested in using games to explore the nuances of the impact politics has on real-world situations.

This includes some unlikely candidates such as Root, a game about conflict in a woodland kingdom of cute animals. But Ruhnke is adamant that it belongs, despite appearances.

“For politics, we find definitions like making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations between individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status,” he says.

“So, if a game shows us dynamics about who will govern and how, or who gets what when, then I would deem it political.”

And if you play Root, you’ll find it has a lot to say about the struggle for power between rulers and those they rule. Meanwhile, Evil Corp, a satirical family game, sees players take the role of billionaires advancing nefarious schemes.

“What a designer is saying about a particular political context is as important or more important than, the game’s mechanics,” suggests its designer Alfie Dennen.

“Collecting tax to fund conquest is one thing, but offering insight into the impact of that taxation on an imagined populace is what separates out games like Root or Labyrinth.”

Political-simulation games are not new, but until recently computer titles have dominated the field. While they can include more detail, they’re mostly solo affairs, whereas tabletop games are multi-player.

For Dennen, this is critical. “As you experience a game together, insights and conversation naturally emerge,” he says. “Many who might not otherwise actively seek insight into politics might still have board gaming as a hobby.”

Zain Memon, who designed SHASN (meaning governance), in which players must explore ideological commitments to gain resources for an election, agrees. “Board games offer the opportunity to share interactive experiences with other players,” he says. “If you want to experience the cutthroat nature of politics, what better way to do so than by combating a real-life opponent sitting in front of you?”

What these designers are seeking to do is to use games as a medium to get people learning and talking about politics. This is a role traditionally entrusted to the written word but Ruhnke sees it as a key advantage in playing games instead.

“Politics are not linear or static, but ever in motion,” he explains. “A set narrative, such as a written political history, is far less likely to represent and convey the real-world experience of politics than a game in which we interpret and act on such dynamics.”

Memon sees a further advantage “Films and books are amazing mediums with their own strengths, but their experience tends to be didactic,” he says.

“The interactive nature of games, on the other hand, makes them empathy machines that allow you to step into the shoes of a character and briefly inhabit their life. The best games allow designers to co-create narratives with the players every time the box is opened.”

As you might expect, there’s a degree of evangelism about the under-explored use of such games in formal education. “They’re a potent media for learning about any kind of mass human affairs,” Ruhnke says. “But games must give players agency. That means that an instructor must give up some control to the students.

“One fear may be that the students will take the exercise in an unanticipated – even counterproductive – direction, away from the learning objectives. Also, I detect a bias against games in formal institutions, be they academic or government. Games connote frivolity rather than seriousness.”

Due to this perception, political games are often accused of trivialising important subjects. For Runhke, this is a problem of context. “Games can trivialise important or distressing subjects,” he admits. “So can books, columns and films.

“I suspect that, as with games for teaching, we see games as more trivial than writing or movies, without good reason. My approach as a designer is to present a plausible and accessible model, in hopes of exploring and illuminating history rather than either glorifying or condemning it.”

But the other designers are keen to point out that trivialisation can cut two ways. “Countless political games can – rightly – be blamed for trivialising important issues,” points out Abhishek Lamba, who co-designed the upcoming SHASN expansion AZADI (liberty), alongside Memon. “Board games have a colonialism problem. As an Indian, I can say that in most narratives, I am the ‘worker’ you put on the board. I am the barbarian whose land you ‘discover’. I am the ‘savage’ you try to ‘civilise’.”

Despite this, designers feel it’s important that games continue to explore these subjects. For board games to be taken as seriously as other creative mediums, the industry must consider the narratives that we consume and co-create.

Are we highlighting the exploitation inherent in colonialism, they ask, or are we romanticising past oppressors? Are we parroting centuries-old stereotypes, or are we creating spaces where the subaltern can speak?

Dennen takes up the theme. “When creating a game about imperial conquest, to what degree is it your responsibility to highlight or expose negative outcomes of that age such as slavery?” he asks. “As long as you have a philosophy driving your design choices, whether others agree with them or not, you have a defensible position to say whatever you want through your games.”

While it seems unquestionable that we can learn a lot about politics and history from games like these, what’s less clear is whether they’re able to address the burning political issues of the day.

Those who’ve played Labyrinth or A Distant Plain may have had a better grasp of the realities of Afghanistan than, it seems, some in government. But what about domestic issues? What about the tide of divisive populism that’s engulfing many Western nations?

It’s something that Memon sees SHASN directly addressing. “It confronts players with the political rhetoric used across the spectrum. Whatever your political beliefs, the game compels you to listen to the other side. It attempts to deconstruct the polarisation problem by breaking down the system that rewards uncompromising, hard-line stands.”

Dennen is more circumspect. “Our problems of polarisation can only really be helped by re-examining and working towards recreating how our economies work,” he says.

“Online advertising and the attention economy have spawned a Dante’s Inferno of division and polarisation and it won’t matter how wonderful a board game is, it’s not going to make a dent. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try.”

Five more games to try:

Any of the games mentioned in the feature make a great place to start exploring this corner of gaming. Here are five more worth checking out.

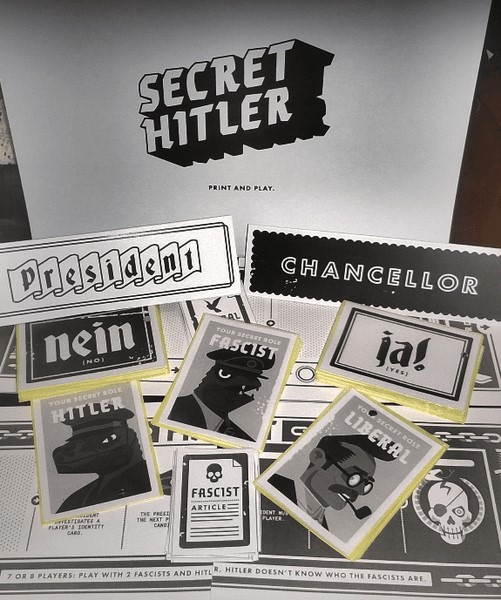

Secret Hitler

In this bluffing game, each player gets a secret role: liberal or fascist. Players then vote on abstract “laws”, with liberals racing to identify fascists before they can seize control of parliament. It’s an illustration of how dangerous populists can hide in plain sight until it’s too late.

This Guilty Land

Cast as abstract concepts, Justice and Oppression, players explore the thesis that the American Civil War was the only means of ending slavery. A third faction, Compromise, shows how well-meaning parties can perpetuate an unethical status quo. There are obvious parallels with the modern fight for equality.

Fire in the Lake

Another Volko Ruhnke game, this is a complex simulation of the Vietnam War. With the US and South Vietnam players limited in the ways they can tackle hidden Communist cadres, it’s a great lesson in the limitations of Western imperialist power.

An Infamous Traffic

An economic game that casts players as profiteers, selling opium in 19th-century China. It is unflinching in its portrayal of colonial history, from missionaries riding on the coat-tails of exploitation to the way players exchange their blood money for trivial gewgaws such as fancy clothes.

The Mechanic Is the Message

This isn’t one game but a series of semi-artistic titles from video game designer Brenda Romero. They include Train, where players must optimise a transport network that’s later revealed to be for Jews in Nazi Germany, and One Falls for Each Of Us that helps players visualise the scale of suffering on the Trail of Tears (the forced displacement of Native Americans in the 19th century), with 50,000 playing pieces.