If one country’s economy is averaging growth of 0.5% and continues to do so and another manages growth of 3.5% and continues to do so, then it is inevitable that the faster-growing economy will overtake the slower-growing one at some point.

Perhaps one will not overtake the other in terms of absolute size – Luxembourg is a very rich country, but it is never going to be larger than the USA – but in terms of GDP per capita; the size of the economy divided by the size of the population. If one continues to grow faster than the other, then the overtake is bound to happen.

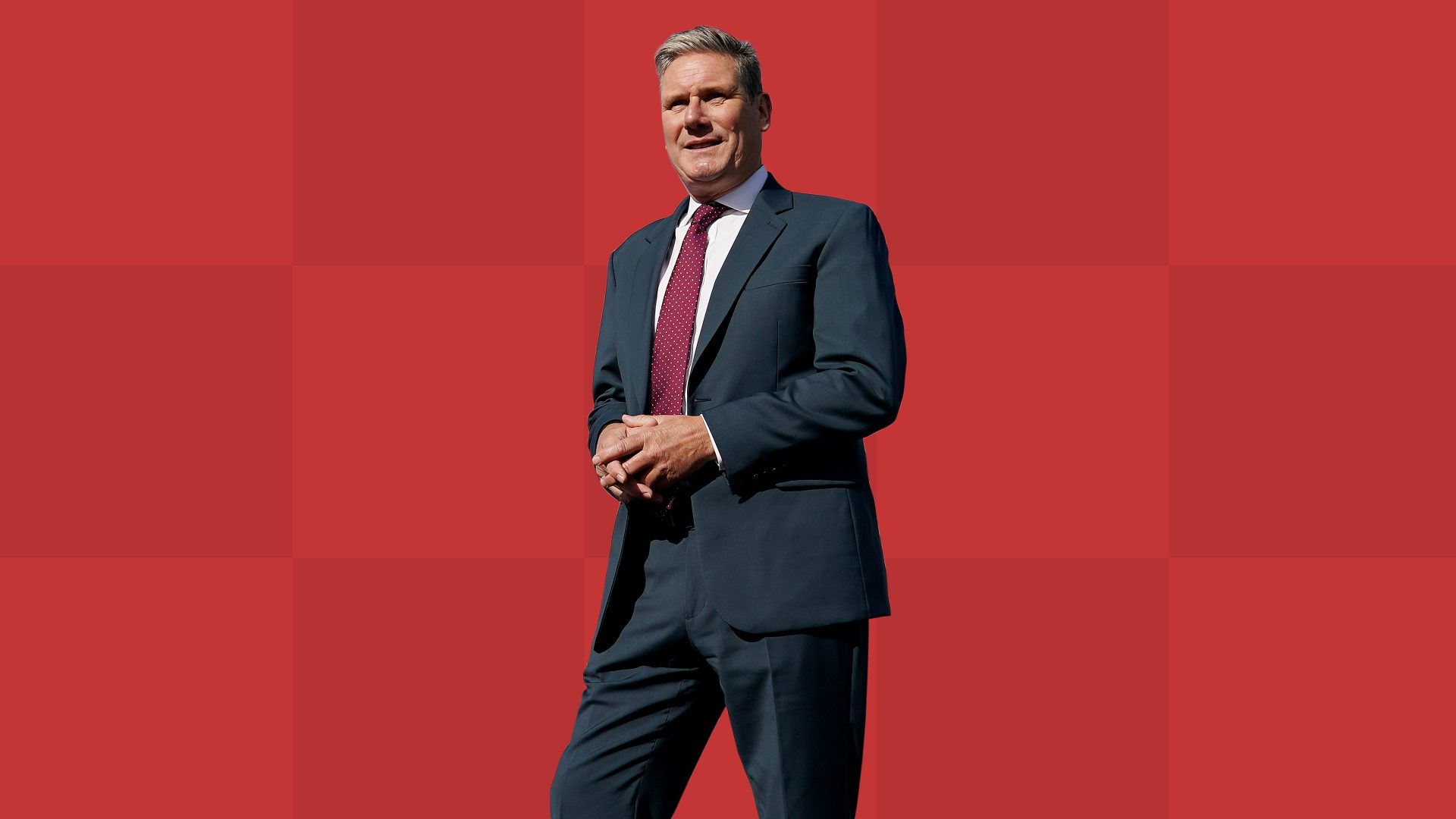

On Monday, while all eyes were on Windsor, Keir Starmer was accused of talking Britain down when he pointed out that Poland will soon overtake the UK because it is growing so much faster than we are. While that is an absurd charge, perhaps the comparison is a tad patronising. Poland stopped being a backward-looking, permanently poor country many years ago.

I visited it several times in the early 2000s and it was attracting huge levels of investment, mainly from German, Dutch and French companies all along its Western border. Huge companies took advantage of the low-paid but excellently trained and young Polish population to produce components and finished goods more cheaply than they could at home.

It was and is a win/win. Poland got higher growth and European manufacturers got cheaper manufacturing.

But that means it is going to be difficult for the UK to stop its relative decline. We do not have a young, cheap, well-trained, multilingual population. We are a less attractive place to invest and expand.

Labour is using Poland as a warning that the UK’s growth rate is far too low, which it is. Its ambition is to make the UK the fastest-growing economy in the G7. This is a good, headline-grabbing ambition but not a real one. No country can possibly grow faster than all its rivals, all the time. But Labour’s stance is a good way of showing how bad things are.

That is necessary in order to end one of the UK’s biggest problems – its unjustified feeling of exceptionalism.

This could be better described as head in the sand-ism. The UK is not a world leader in technology, it is not the best place to invest in Europe. It is not a uniquely free market or low-tax economy. Its infrastructure is awful, its investment levels are terrible, its armed forces are weak, its health service is breaking down and its legal system is grinding to a halt.

It is also no longer a member of the EU or, more importantly, its single market.

If it wants to fend off the threat of being overtaken by Poland, it needs to address all these problems. Yet it is lumbered with a government that insists that tax cuts and only tax cuts are the best way of boosting growth.

Competing against that by proposing better training, higher investment, better schools, better access to Europe and better public transport, is very difficult. Because the government just lies and says we can do that and cut taxes or to be more specific, we can do that because we cut taxes.

But if you want to avoid being overtaken by Poland and then half a dozen other former communist states, you are going to have to win that argument first.