Kacper Olenska is an MP’s assistant, and I first met him in the local branch office of PiS, the Law and Justice Party of Poland, the hard right party that has taken Poland towards anti-democratic populism and European political isolation. On that day, Kacper gave me a tour, and showed me portraits of Popes Francis and John Paul II, as well as a poster of Donald Tusk, leader of the opposition KO party. He was depicted alongside the slogan, “YES FÜR DEUTSCHLAND”, an unkind reference to Tusk’s German-speaking background.

The general election in Poland was accompanied by a referendum, and the four questions had been phrased in such a way that the only possible response was “NO”. One of them asked voters whether they were in favour of: “the admission of thousands of illegal immigrants from the Middle East and Africa, in accordance with the forced relocation mechanism imposed by the European bureaucracy.”

Kacper is unusual because he is only 22 and PiS voters tend to be old. What attracted him to the stridently conservative ruling party? “The elites from the old parties sometimes weren’t really proud of who we are,” he explained, “and thought that we always needed to be more European.” It irritated him to see them sneer at nationalists’ marches on Poland’s independence day.

Kacper is conservative to his core. Travelling is good, he says, but “too much is dangerous. You can lose your roots.” He is not religious, he says, but guided by Christian values like love and respect. He explains that he has outgrown his youthful flirtation with the radical Confederation party, calling them “unrealistic”.

We talked about governance in Poland. Is it not true that the state broadcaster, TVP, has become a party mouthpiece? And does the referendum not demonstrate PiS’ rather callous attitude towards democracy? “Stop recording,” says Kacper. I duly oblige. The only way I can start again is by assuring him I will not identify him. Kacper is not his real name.

He took a deep breath before speaking slowly. True, “PiS breaks some rules,” he said, but so did Tusk back when he was in power by extraditing Poles despite this being unconstitutional at the time. True, justice is sometimes politicised, but “justice has been a problem for the whole history of the Third Polish Republic.” It is not PiS per se, said Kacper, but all of Poland that is harming democracy by ignoring the rules whenever it suits. Kacper added that he would not trust Tusk’s KO party to be impartial in overseeing the justice system.

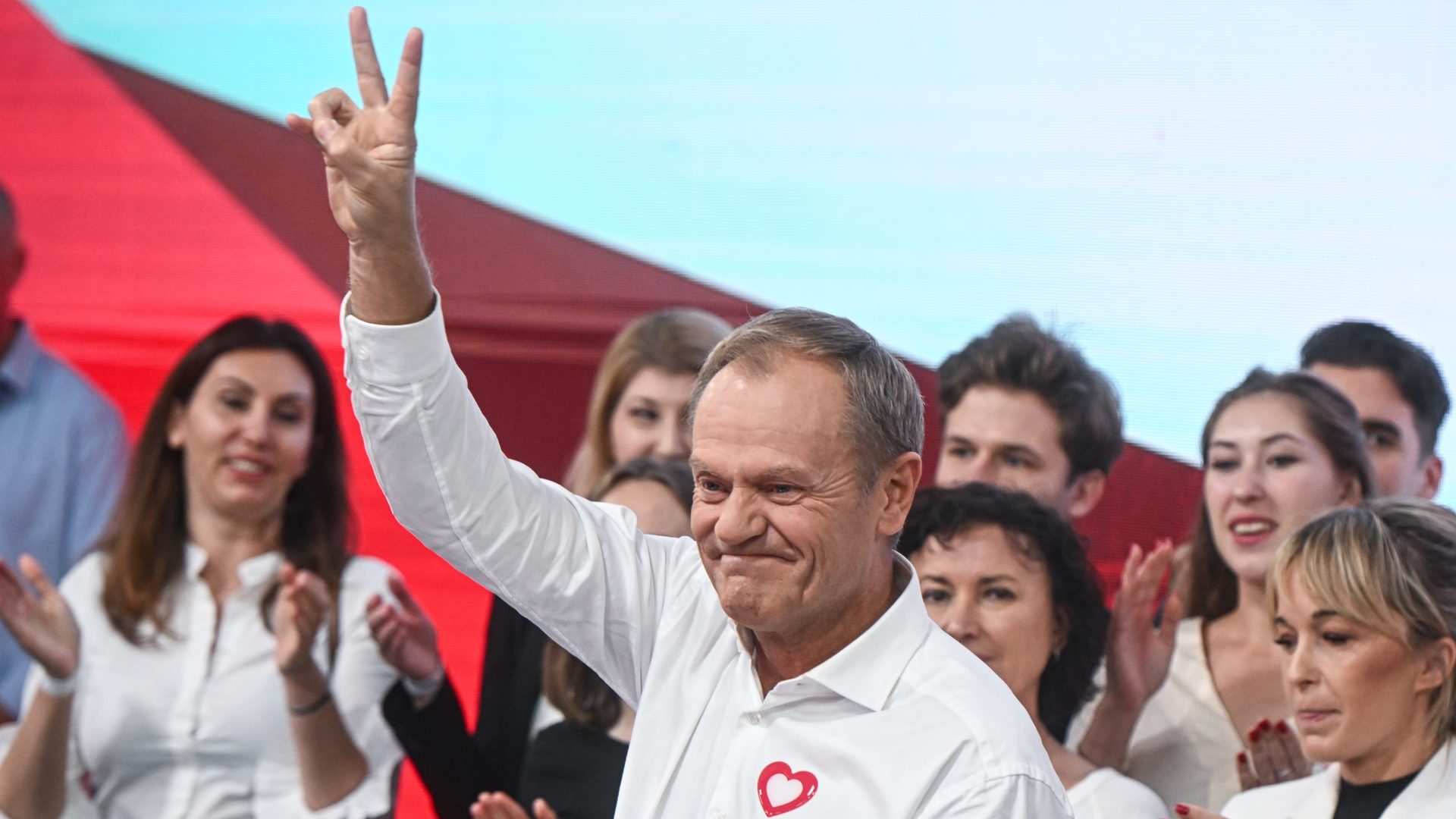

The results of the Polish referendum came through on Sunday – it was a damp squib. With only a 40% participation rate it fell below the 50% threshold needed for the result to hold. But the parliamentary elections were not a damp squib – PiS was the largest single party, but with 36.8 per cent of the vote it fell short of a majority and doesn’t have the coalition partners necessary to form a government. Tusk’s KO party won 31%, and because he can almost certainly build a coalition with the centrist Third Way party (13.5%) and the Left party (8.6%) he declared victory within minutes of the exit poll. Polish friends began texting to say they were drinking champagne. Others preferred wine and saved the champagne for the moment the exit poll was confirmed.

I got in touch with Kacper. The exit poll is clear. The three centrist, more liberal parties together have a majority, while PiS and Confederation are far short. He didn’t say much, so I badgered him for an answer. He didn’t want to talk about the referendum, and when I pressed him on the parliamentary result, he talked about how hard it is for any party to form a coalition government.

He might have a point. Weronika Chruszcz, a student and supporter of the centrist parties, was holding back on the celebrations. She was worried that Tusk might not be able to form a coalition. “If they screw it up and the right wins again,” she told me, “I’m moving country.”