“I think God himself stays informed about the world in no other way than by reading the newspapers,” wrote the German playwright Bertolt Brecht in the dying days of the Weimar Republic. The newspaper was not simply reading material for the writer, it was also his medium.

When Hitler rose to power in 1933, Brecht bailed out of Germany, spending 15 years in exile, country-hopping as the Nazis stretched their malign claws across Europe. Between 1941 and 1947 he lived in the United States, there writing some of his finest plays: The Caucasian Chalk Circle; Mother Courage and Her Children; The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui; The Good Person of Szechuan.

Brecht’s peripatetic lifestyle shaped by war and economic crisis gave him his themes: poverty, ruin and military destruction, while press photographs, postcards and art books gave him the means to organise his ideas.

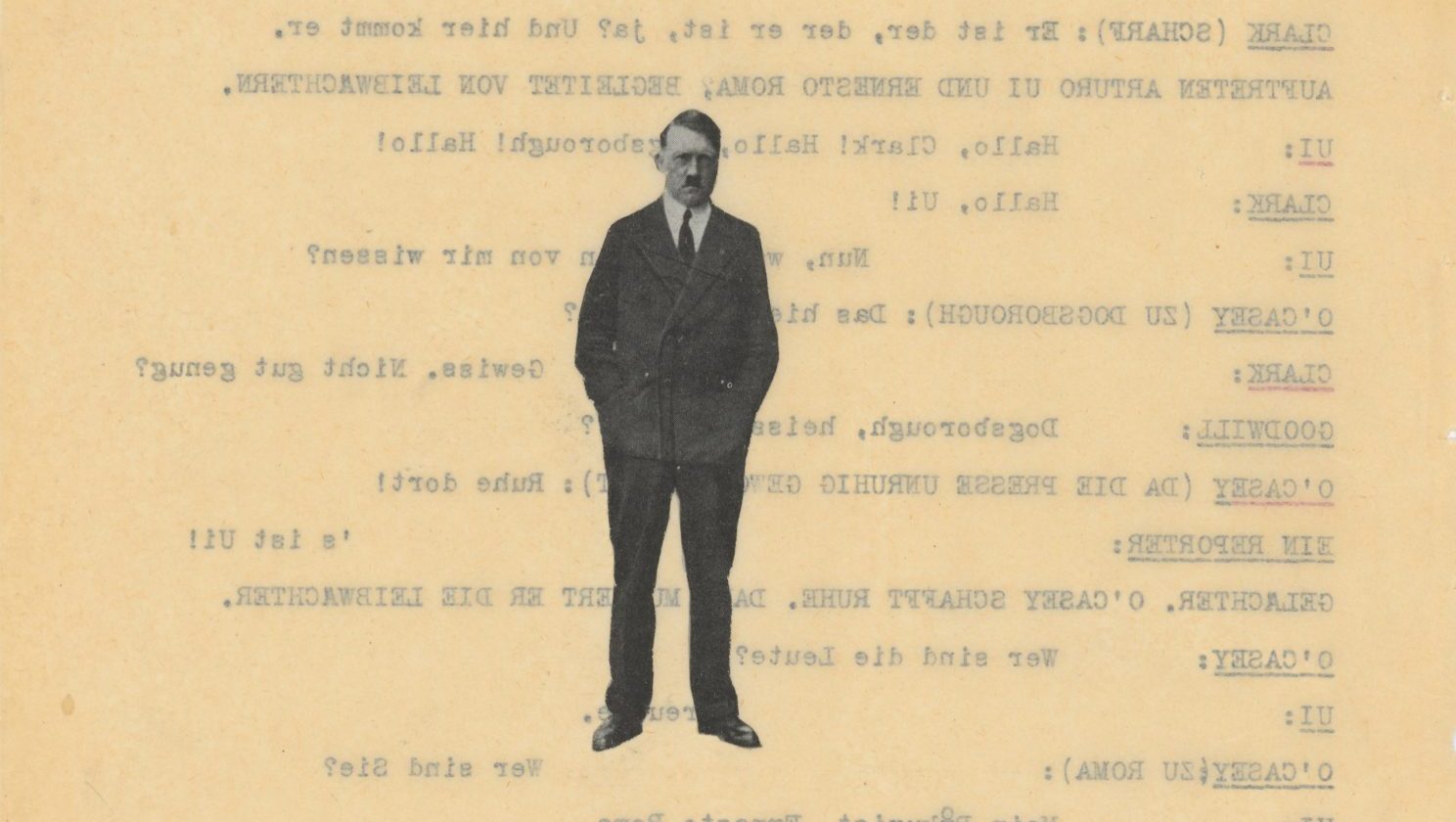

Fragments, an excellent exhibition at Raven Row, London, illustrates how Brecht’s plays were informed by his extensive use of montage, a practice of cutting out black-and-white photographs from newspapers and pasting them on to any scrap of paper in his possession. The resulting skin-like layers bear the traces of rusted paper clips, the paper so Bible-thin that the reverse side shows through, patched with text or scripted dialogue.

Overlays and extensions to unbound sheets, typed epigrams and annotations in red pencil create an architecture of print and image, a paper stage on which culled pictures were marshalled next to each other in playful or ironic juxtapositions.

This method of working gave the “master of paste-ology” the freedom to move his ideas around while also on the move, without access to a theatre or a company. “At present, all I can write are these little epigrams, first eight-liners, and now only four-liners,” he observed, exiled in Finland.

Fragmentation as a literary or dramatic device must also have appealed as it stood in opposition to the rigidity and single viewpoint of Nazi rhetoric and the ruthless regularity of the regime’s graphics and architecture. Like many artists and writers of his generation, Brecht recognised that a new language was required.

“After the Great War, life goes on in our ruined cities, but it is a different life, the life of different or differently composed groups, guided or thwarted by new surroundings, new because so much has been destroyed,” he wrote. Picasso and Braque had begun the process in the early 1900s with Cubism, pulverising objects and figures into shards and facets viewed from multiple angles. They introduced lettering and inscriptions, moving from paint and canvas to papiers collés, adding excerpts from the newspaper to a paper surface to create a literal slice of everyday life.

In the 1920s, the Dadaists of Berlin “turned collage into a political pamphlet” (Jean Clay). In using photomontage, artists such as Otto Dix, George Grosz, John Heartfield, Raoul Hausmann and Hannah Höch questioned the documentary truth of photographs by reassembling them with satirical bite. Their influence was felt in the loud, bold typography of Dadaist manifestos, poetry and literature, in which type came at the reader from all angles, in a variety of fonts and sizes. “If a novel cannot be cut into ten pieces like an earthworm and each part moves on its own, it isn’t much use,” wrote the German novelist, Alfred Döblin, in his ‘theory of the autonomy of the parts’.

Interrogated by the House of Un-American Activities Committee in the States for his Marxist leanings, Brecht returned to Europe, finally settling in East Berlin where he died at the height of the cold war in 1956. His collected papers, which numbered over a million items, were preserved by his wife, Helene Weigel, in the Brecht archives.

The exhibition in London shows a fraction of these. Displayed in vitrines and on walls across three floors are albums, plot plans, journal entries, a war primer, two films and material relating to plays and playlets, while twice a day a 90-minute performance follows this paper trail, in rooms and up stairways, so that the audience becomes visitor-turned-voyager.

On entering the main gallery, the first images include the pock-marked face of Hitler’s chief propagandist, Joseph Goebbels, looming out from a cosmic darkness. This face could almost be a portrait by Picasso, with its almond-shaped eyes, heavy nose, thin lips and an ear that looks stuck on at a weird angle. “I am the doctor, doctoring the news,” reads the translation of the typed text beneath it.

For Goebbels, it was radio and film, rather than the newspaper, that were his disinformation disseminators of choice. Close by, another newspaper cutting depicts people sheltering in a subway, lying on newsprint with newspapers covering their faces, trying to catch some sleep.

Below this is a photograph of Mussolini addressing a square packed with crowds as far as the eye can see. The recurring subjects that appear throughout Brecht’s pages are the dictators of the age – Hitler and Mussolini – and how they dressed, how they stood, what gestures they used – offset by the people, common humanity, a kind of monster-versus-masses dichotomy, pasted in cutting combinations.

In a page from Picture Post 1939, Adolf Hitler is shown with his fists raised and his face screwed up in hate; underneath it is a German schoolboy repeating the Führer’s gesture in childish imitation, a Nazi newspaper lying on the desk in front of him. “The Model for Every School Child” is the publication’s wry caption to the Hitler photograph.

How, then, does this immense wealth of material translate into performance? What does montage look like when it is inside a play? A cast of 12 daily enact four unfinished plays from the late 1920s – The Breadshop, Fleischhaker, Fatzer and The Flood – successfully plaiting two different mediums together. Each dramatic scenario is separate yet interwoven, expressing Brecht’s desire to open the work up to future reinterpretation, to reflect the performers’ times and locality.

The costume and set designers have done a masterful job in realising a world of want, fragility and transience. Gallery floors are matted with packing box cardboard, badged with barcodes and address labels; pages of script are tacked to the walls; a large battle tank is represented by a black plywood cut-out. Props are similarly sculpted from cardboard or – as in the case of the two competing Capitalist bull masks – fashioned from hessian sacking with newspaper horns.

The costumes are simply wonderful: a fusion of circus-cabaret theatricality, echoed in clownish make-up and hats; a hybrid mash-up of tattered and torn cream, black, khaki green and buff garments, stitched roughly together with flashes of red that recall Brecht’s correcting pencil.

Brecht’s theatre breaks the illusion of the fourth wall so that characters address the audience directly, bringing awareness that they are watching a performance. In The Breadshop, the baker, Meininger, asks us, “How do people get their bread? Money! Work! Looting!”

Widow Queck’s eviction from her home for not paying her bills has clear parallels with today’s cost-of-living crisis, her life is chopped to pieces and everything she owns is taken or axed. The fascination with gesture as seen in the photographs is replicated by the actors as a form of characterisation and social comment.

In Fleischhacker, the two bulls engaged in wheat market speculations strike a freeze-frame pose, and in The Flood, a deluge assumes Biblical proportions, driving the performers and audience upstairs to escape it. “It’s raining cobblestones, then it rains from the earth to the sky…. people flee the cities to the mountains!” one character exclaims, and we cannot fail to think of our own climate-crazed days, just as the ominous black tank and deserting soldiers call to mind the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

I would have liked to have learned more of Brecht’s collaborators. The playwright’s partnership with composer Kurt Weill is well known, but there were others involved specifically in the paste-ups and the editorial side: Ruth Berlau, Elisabeth Hauptmann, Margarete Steffin.

Otherwise, I know what I will be doing with my old newspapers from now on. Scissors and paste, anyone?

Brecht: Fragments is at Raven Row, London, until August 18, 2024. Performances run until July 28