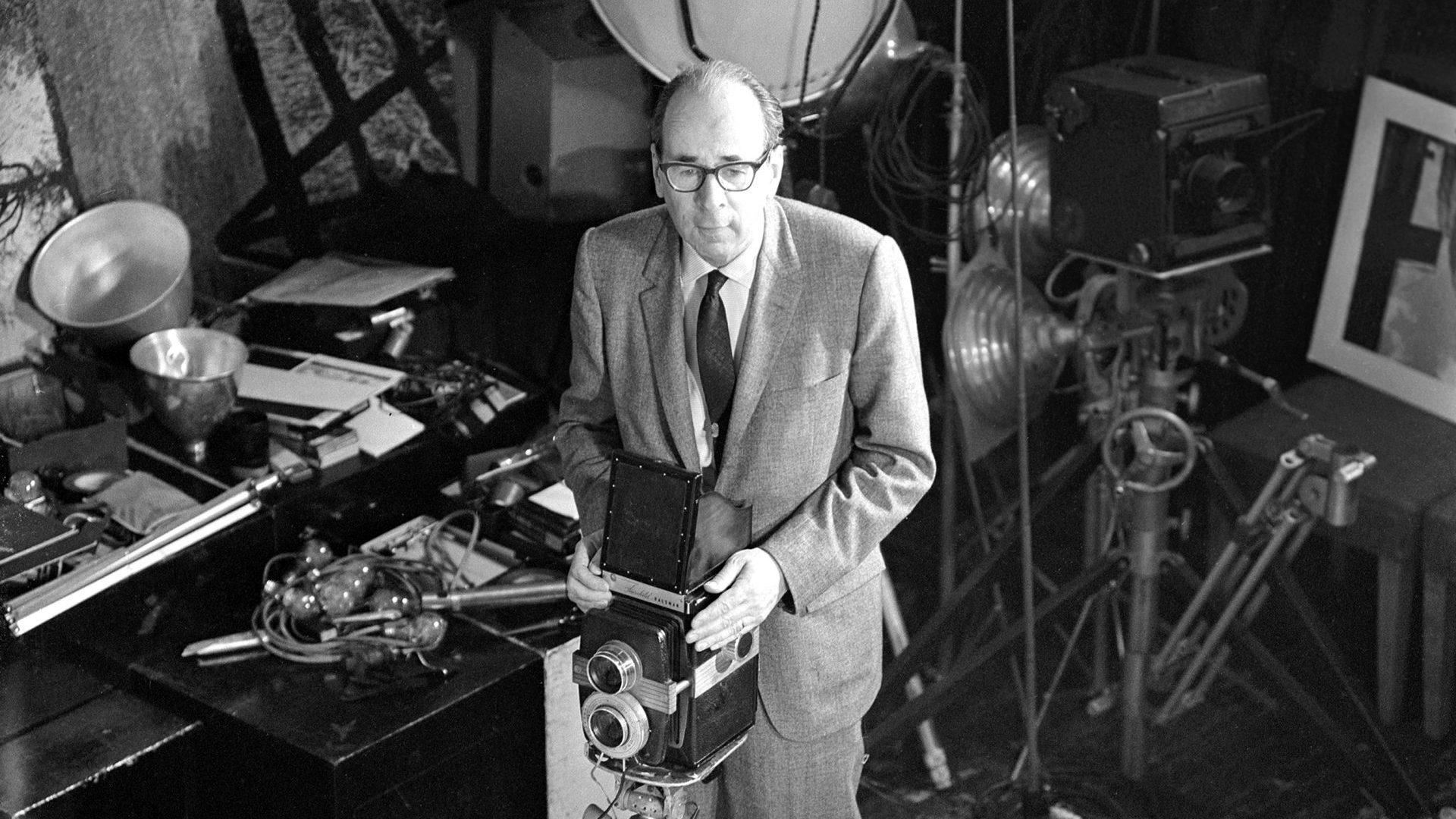

New York, 1947. It’s two years since Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and Albert Einstein is sitting at his desk while the photographer Philippe Halsman sets up lights around him. Einstein hates having his photograph taken at the best

of times and the clanging and ratcheting irritate him as he leafs through some letters.

Halsman was different, though. Einstein and Halsman go back to the years before the war, to Paris and beyond. There was something about him, a warmth, an effortless charm, that he hadn’t detected in many people before or since. That’s why he first helped the Jewish photographer to escape a remarkable miscarriage of justice, then to get out of France as the country fell to the invading Nazi forces. And here he was, two years after the end

of the war, as gentle as ever, even when bolting light stands together.

Thoughts of the conflict flooded Einstein’s mind and a familiar melancholy weighed down on him. Before he knew it he was talking to Halsman, expressing the anguish he felt that his Theory of Relativity had contributed to the development of nuclear weapons and the deaths of untold thousands. He spoke of the cold fear that engulfed him when reading of influential political figures in America discussing a pre-emptive nuclear strike on the Soviet Union as a plausible alternative to the Russians matching the US’s nuclear arsenal.

As Einstein spoke Halsman picked up his camera and the physicist looked up

into its lens. The portrait it captured showed a haunted man, the weight of

guilt pressing almost visibly on him, the deep melancholy in his dark eyes almost infinite.

A few months later Halsman photographed another familiar subject, the surrealist artist Salvador Dalí. This portrait took a little more preparation

than Einstein’s; Halsman’s vision, based on Dalí’s painting Leda Atomica,

involving a moment and a tableau suspended in both time and the air. Thin wires held Dalí’s easel, stool and a canvas of Leda Atomica above the ground while at the edge of the frame Halsman’s wife, Yvonne, held up a chair. Assistants were ready with three cats and a bucket of water, which on a given

signal would be launched into the air while Dalí, holding palette and brush, leapt as high as he could.

It took 28 attempts to capture precisely what Halsman wanted but the result, Dalí Atomicus, became one of the most famous images of the artist, leaping skyward as a wave of water crosses the shot with three airborne felines.

If ever two photographs capture the essence of men who helped to define the 20th century it was these, shot just weeks apart. Contrasting in concept,

execution and personality, it’s hard to believe they are even the work of the same photographer.

“If a photograph of a human being does not show a deep psychological insight it is not a true portrait but an empty likeness,” said Halsman, laying

out his philosophy. Few photographers have emulated him in successfully

escorting the viewer inside the mind of a subject in the fraction of a second it takes to preserve an image on film.

It helped that Halsman was able to easily win the trust of some of the greatest figures in modern cultural and political history: John F Kennedy, Marilyn Monroe, Groucho Marx, Winston Churchill, Jean Cocteau, Pablo Picasso. Evidence of that trust is most overtly visible in a series of pictures

taken during the 1950s in which he persuaded his subjects to leap into the air.

“The subject, in a sudden burst of energy, overcomes gravity,” he said of what he called “jumpology”. “He cannot simultaneously control his expressions, his facial and limb muscles. The mask falls and the real self becomes visible. One has only to snap it with a camera.”

In this way he managed to capture an unexpected side to a range of personalities in a way nobody had before. Richard Nixon jumped for Halsman’s camera. So did Brigitte Bardot, Audrey Hepburn and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, the former Edward VIII and Wallis Simpson, who

removed their shoes and jumped together in their stockinged feet.

There’s a joy about these pictures, even in subjects like Nixon and the duke who were hardly renowned for their happy-go-lucky natures, and it could be that Halsman’s life before arriving in the US had left him craving joy wherever he could find it.

He had disembarked at Miami from the SS Winnipeg in June 1940 practically penniless after a nerve-wracking three-week voyage from Bordeaux. The ship, which a few months earlier had been chartered by the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda to evacuate refugees from the Spanish civil war, carried hundreds of traumatised people escaping the Nazis and Einstein had pulled strings to make sure Halsman, Yvonne and their daughter were among them.

The Latvian-born photographer had been living in Paris for a decade, establishing himself as a portrait photographer of distinction, but when Hitler’s army arrived in the city Halsman knew he was in danger. After all, he had arrived in France in the first place as something of a Jewish cause-célèbre.

In 1928 the 22-year-old Halsman was on a walking holiday in the Austrian

Tirol with his father when he heard a shout behind him and turned to see his

father tumbling down the mountainside. By the time Halsman reached him he was dead from a head wound, his wallet lying empty nearby, a stone smeared with blood and hair dropped by his side. With antisemitism rife in the region Halsman was charged with his father’s murder and, despite the evidence being circumstantial at best and prosecution witnesses being called from the proto-Nazi Heimwehr movement, sentenced to 10 years in solitary confinement.

In response to a case that had echoes of the infamous Dreyfus affair, a high-profile campaign was launched backed by leading European Jewish figures such as Sigmund Freud, Thomas Mann and Einstein. It took two years but Halsman was eventually pardoned and released.

Hence when murderous state-sponsored antisemitism marched into Paris in the summer of 1940 Halsman knew he must escape France as soon as he could. Einstein helped to secure visas and the family made for Bordeaux and

the Atlantic beyond.

Three months after arriving in the US, Halsman found work with the Black Star photographic agency while making portraits in his spare time. One of his first subjects was an aspiring model named Connie Ford, whom he photographed lying on a US flag. When the image was picked up by Elizabeth Arden for a lipstick advertisement, Halsman was on his way to becoming one of the greatest portrait photographers of all time, his services

sought by those in high office, high society and the highest echelons of modern culture.

“[My] fascination with the human face has never left me,” he said in the early

1970s. “Every face I see seems to hide – and sometimes fleetingly to reveal – the mystery of another human being. Later, capturing this revelation became the goal and the passion of my life.

“I became a collector of the reflections of the innermost self of the people who faced my camera.”