Scientists haven’t discovered alien life on another planet. Whether or not the University of Cambridge team of astronomers whose findings made recent headlines are “99.7% confident” they have spotted a telltale signature of life elsewhere, most informed scientists don’t consider the results compelling evidence for such a claim.

The work, led by astronomer Nikku Madhusudhan, is certainly intriguing. The researchers have used the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), launched in late 2021, to study the atmosphere of a planet called K2-18b, approximately five times Earth’s diameter and 8.6 times its mass, and orbiting a star 120 light years away.

They believe they may have detected two closely related chemical compounds in K2-18b’s atmosphere for which it is hard to think of any source other than life. On Earth, these compounds – dimethyl sulfide (DMS) and dimethyl disulfide (DMDS) – are produced by marine plankton. The implication is that some kind of (probably microbial) life on K2-18b may be pumping the stuff into the atmosphere.

There are, however, a lot of “buts”. Detecting the chemical composition of planets around distant stars (exoplanets) is tremendously difficult and has only recently become possible at all; it’s the kind of task the JWST was created for. We have known for years now that exoplanets are common – most typical stars will have planetary systems like that of the sun. As with the solar system, however, it’s unlikely that most of these planets would be inhabitable by life as we know it, because they would be either too hot or too cold to host liquid water. The “Goldilocks” region of a planetary system in which the conditions seem just right for such life is called the habitable zone. K2-18b lies within the habitable zone of its parent star.

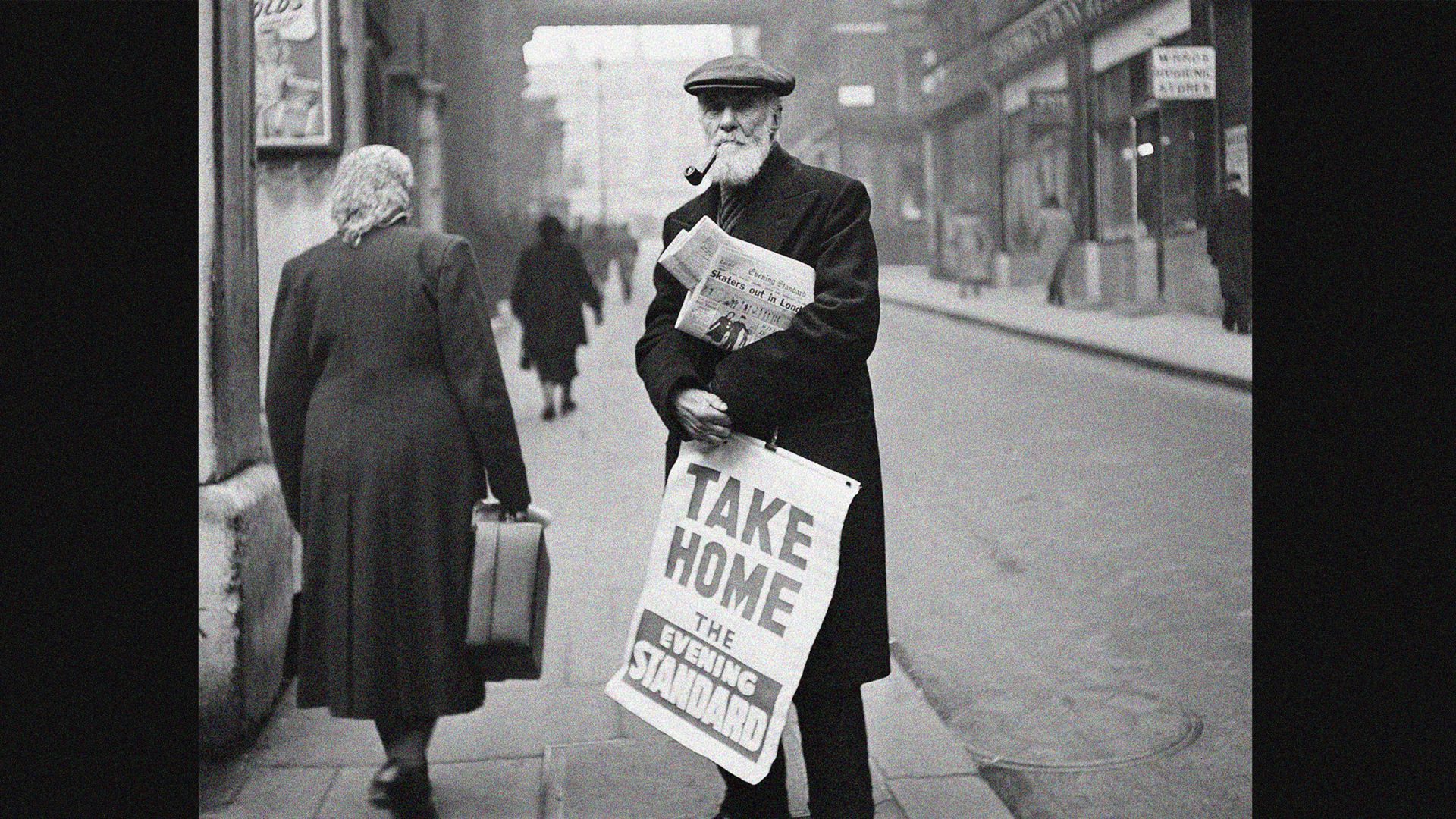

Most exoplanets are detected from the very faint dimming of their star as the planet periodically crosses the face of the star and blocks some of its light. The effect is minuscule – like a gnat passing in front of a car headlight – but our most sensitive astronomical telescopes can detect it. More than 5,000 exoplanets have now been discovered, mostly by this method.

With the best telescopes such as the JWST, there is now more we can deduce from the dimming of starlight. Chemical compounds like those in a planetary atmosphere absorb light at particular, well-defined wavelengths, where their atoms vibrate in resonance. By scanning how this absorption of light changes at different wavelengths, it’s possible to identify the molecule in question – a standard technique called spectroscopy. If they can measure how the tiny dimming of starlight due to a planetary transit changes at different wavelengths, astronomers can figure out which molecules the planetary atmosphere contains. By such means, for example, last year a team of researchers reported the detection of water vapour in the atmosphere of a planet only twice the size of Earth.

This is how Madhusudhan and colleagues looked for DMS and DMDS in the atmosphere of K2-18b, a planet that they suspect is ocean-covered and has an atmosphere of mostly hydrogen. In 2023 they saw a tentative hint of DMS in data from the JWST, but now think they have strong, independent evidence of it using a different instrument on the telescope. “The signal came through strong and clear,” Madhusudhan has said: the researchers say there is just a 0.3% chance that their interpretation is wrong. That might sound pretty certain – but it doesn’t reach the threshold of probability scientists want to see before accepting such a discovery as confirmed beyond reasonable doubt. Madhusudhan says it’s vital to obtain more data before claiming that they’ve detected extraterrestrial life.

That’s putting it mildly. Some experts have questioned whether the DMS detection is as secure as the Cambridge team claims. “This is bad science, worse science communication, and deeply misleading to the public,” said one. “I know we all want to find alien life, but this is not it.”

Even if the researchers manage to firm up their claim for DMS, that doesn’t mean it has to come from a biological source. Just because we don’t know of any source from purely geological processes on Earth doesn’t mean they don’t exist on other planets. Veteran planetary scientist Carolyn Porco told me recently that, because of how little we know about conditions on exoplanets, it’s unlikely we’ll ever get definite evidence of life purely from the chemistry of their atmospheres. As Porco’s sometime mentor Carl Sagan said, extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.