In 2020, the American writer Jane Miller wrote in the London Review of Books: “I resist all talk of ‘loved ones’.” She continued: “It calls needless attention to the likelihood that we all have friends and relations we don’t much like.”

I found myself agreeing. “Loved ones” is not an expression which was in widespread use in Britain until relatively recently, and it never made it into my consciousness until American reports of the September 11, 2001 attacks on New York City started appearing in the British media. Prior to that, we would probably normally have said something like “family and friends” or “friends and relations”.

The Americanism “loved ones” was initially felt to be rather jarring on this side of the Atlantic, because it seemed to ignore the obvious if uncomfortable fact that it is not necessarily the case that all of us automatically love all of our friends and certainly not all of our family, as Miller was correctly pointing out. And some of us over here felt that it was not for American journalists to tell us who we were supposed to love and who not.

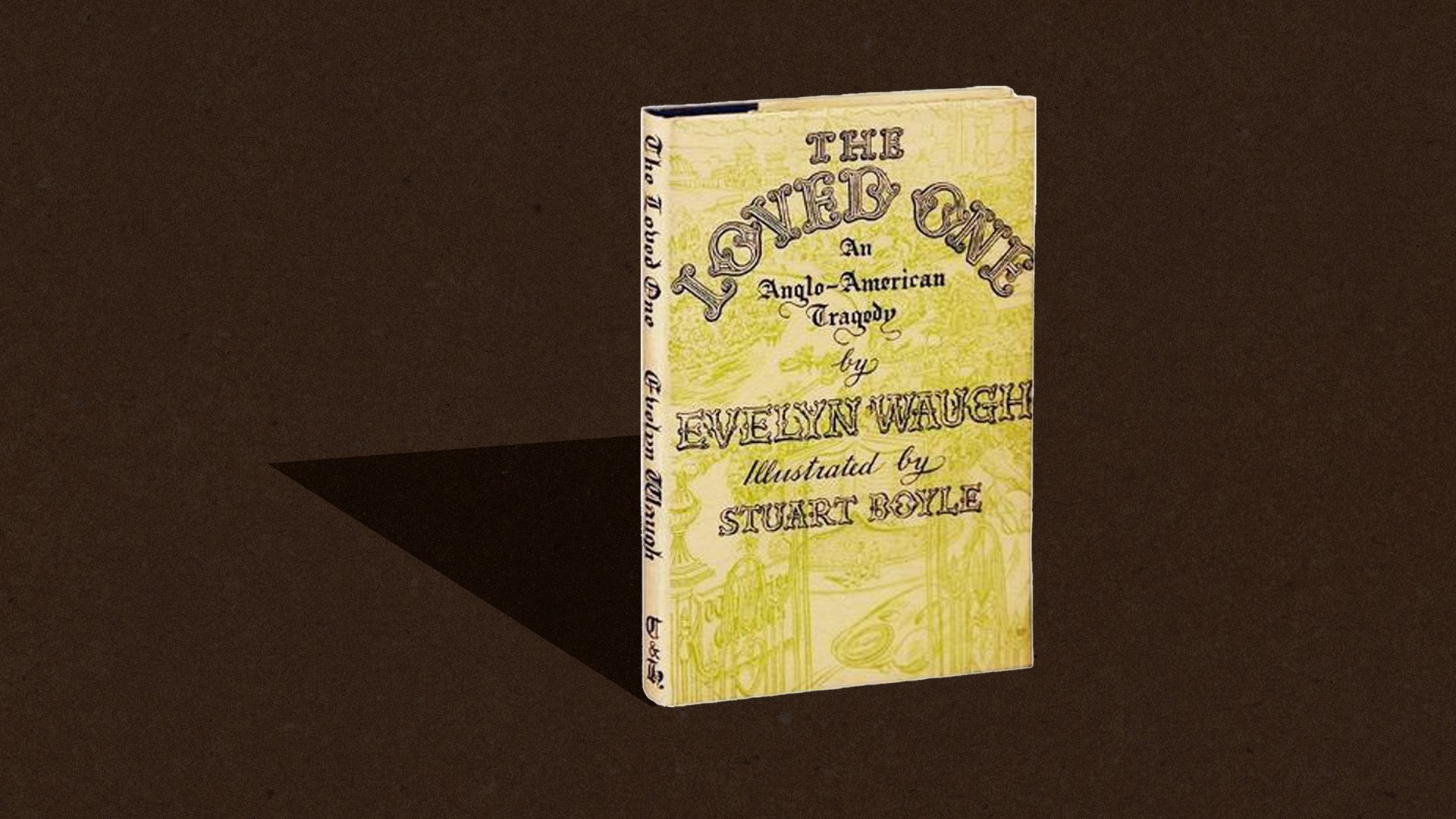

Evelyn Waugh’s famous short work of fiction The Loved One: An Anglo-American Tragedy is a satirical novella which was first published in 1948. It focuses on the funeral business in Los Angeles, as well as on the British expatriate community in Hollywood. Clearly, Waugh found precisely this phrase – loved one – to be an absurd locution, and he used it in his novel to symbolise different aspects of the cultural divide between Britain and the USA, not least in the employment of American-style sentimental euphemisms and touchy-feely expressions filled with sincerity and optimism.

“Touchy-feely,” by the way, was first used in print in the New York Times in 1968 and is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as meaning “given to the open expression of affection or other emotions”.

We can now see this phenomenon illustrated in a number of linguistic usages which have increasingly started coming into use here. I was rather surprised a few years ago when an American academic colleague thanked me for “sharing” a scientific paper with them when, as far as I could see, all I had done was send it.

These days it is also rather common for people to be said to be “reaching out” to one another, which, again as far as I can tell, is simply another way of saying “getting in touch with”.

Languages and dialects all over the world differ not only in terms of words, grammar and pronunciation but also in terms of language usage. When you learn a foreign language, you have to learn not only the language as such but also what the norms are for using it – for example, what the rules are for using greetings, farewells and expressions of gratitude.

Certainly, British people born before about 1970 were by and large not really encouraged in childhood to express affection and other emotions too openly. But as the influence of American usages and attitudes is now seemingly increasing in this country, we will quite possibly see more of this kind of “loved one”-type of development in future – or as some younger people now increasingly seem to say, in a sincerely positive and optimistic way, “going forward”.

AUTOMATIC

Automatic originally meant “self-acting, moving on its own”. The basic root of the word is Ancient Greek autos “self”. In Modern Greek this is pronounced aftós, and has a range of meanings and grammatical functions including he, it, and that, as well as self.