Most of the members of the Germanic language family – the languages which English is most closely related to historically – adhere grammatically to the “verb-second rule”. In a normal sentence in verb-second (V2) languages, the verb has to be the second grammatical element – not necessarily the second word, but the second functional unit.

In German, the perfectly normal sentence Morgen fahre ich nach London translates word-for-word as “tomorrow go I to London”. English speakers would, of course, say “Tomorrow I go to London”. But the German sentence begins with the adverb morgen, and so the next element has to be the verb, in this case fahre “go”. A typical sentence in Dutch also takes the same V2 word-order: Morgen ga ik naar Londen.

When I use the term “rule” here, I am not alluding to the sort of artificial rules which they used to try and teach us at school, such as “you must not start a sentence with and or but”. (The only reasonable riposte to this instruction, by the way, is: why not?)

Rather, I am referring here to genuine linguistic rules of the sort which native speakers of a language learn as infants and follow without realising that they are doing so, such as, in English, the rule that adjectives go before nouns, not after them – which is why English speakers say red wine, whereas in French it is vin rouge and in Welsh gwin coch, with the adjective coming after the noun in both those languages.

During the Old English or Anglo-Saxon stage of our language, which was spoken before about AD1000, it would have been usual to hear sentences such as maran cyððe habbað englas to Gode þonne men, literally “more affinity have angels to God than men” (= angels have more affinity to God than men), where the verb habbað “has” occurs as the second element.

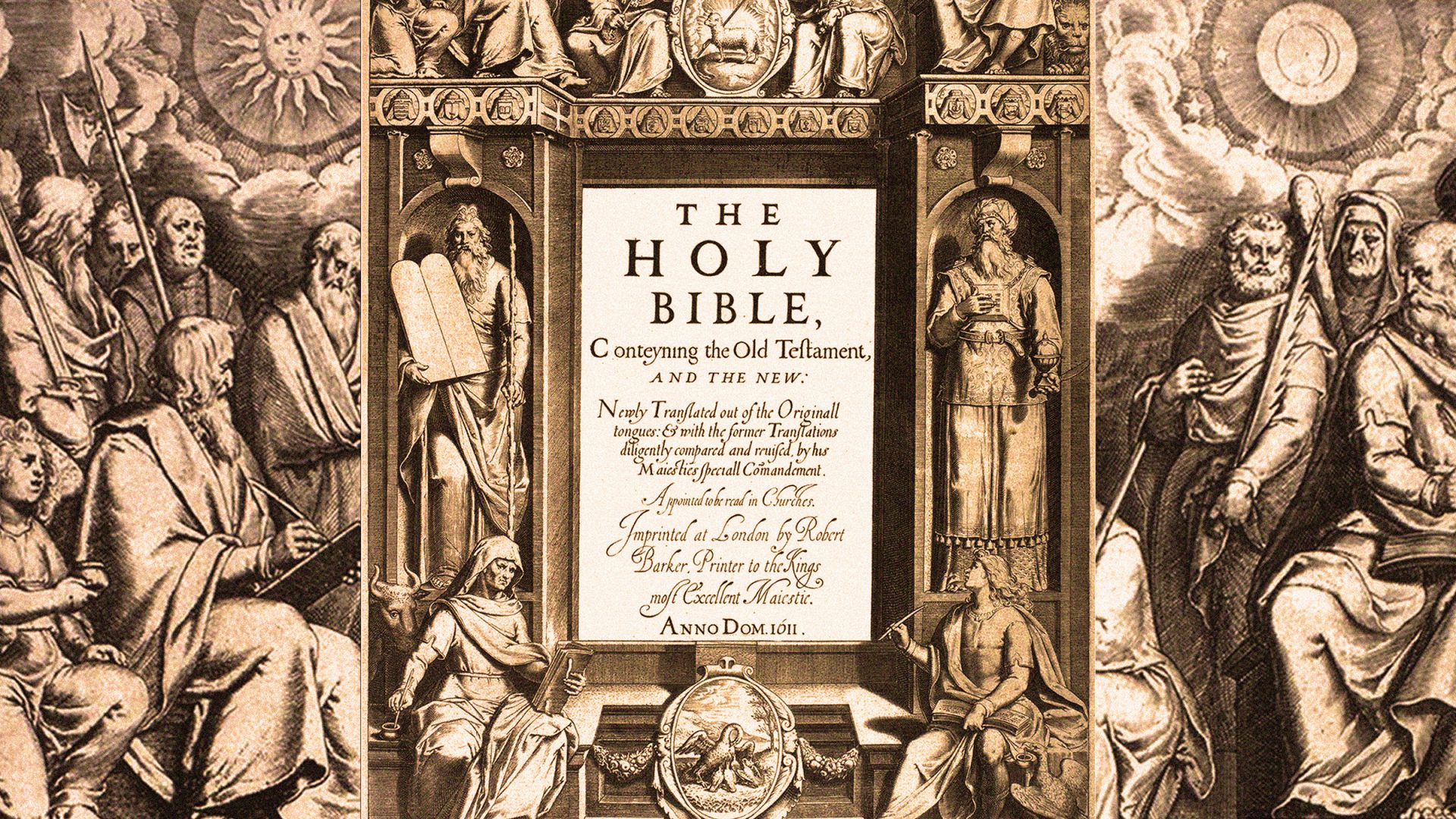

This V2 word order gradually started disappearing during the Medieval English period, but even as late as the King James English-language translation of the Bible, which dates from 1611, we still find in the Book of Genesis sentences such as “Male and female created He them”. In today’s English, we cannot use that order of words, but instead have to write “He created them male and female”.

All the same, in Modern English we can still find quite a few traces of this ancient Germanic verb-second structure left over from previous centuries, hanging on into modern times like ghosts from a bygone age.

Consider sentences like “Especially beautiful was her auburn hair” and “Only very rarely does she leave her office”. These are perfectly normal modern English constructions, even if they are stylistically rather formal. Similarly, in the sentence “Hardly had I begun to speak before the doorbell rang,” the verb had is the second element in the sentence. But in more informal styles, speakers are more likely to frame this as “I had hardly begun to speak before the doorbell rang”.

Other examples of this kind of verb-second inversion in English include sentences like “Never in my life have I heard such nonsense,” where the verb have is the second element. And we see it, too, in replies which occur during common exchanges such as “I don’t like it. – Neither do I”.

KITH

The Old English word cyððe has been translated in the above text as “affinity”, but in origin it is the same word as contemporary English kith, which is known to us today basically only in the phrase “kith and kin”, which can be rephrased in Modern English as “one’s friends and relatives”.