Boris Johnson is clear what he wants his legacy to be. In his resignation speech on July 7, his most prominent boast was his success in “getting Brexit done, settling our relations with the continent after half a century and reclaiming the power for this country to make its own laws in parliament”.

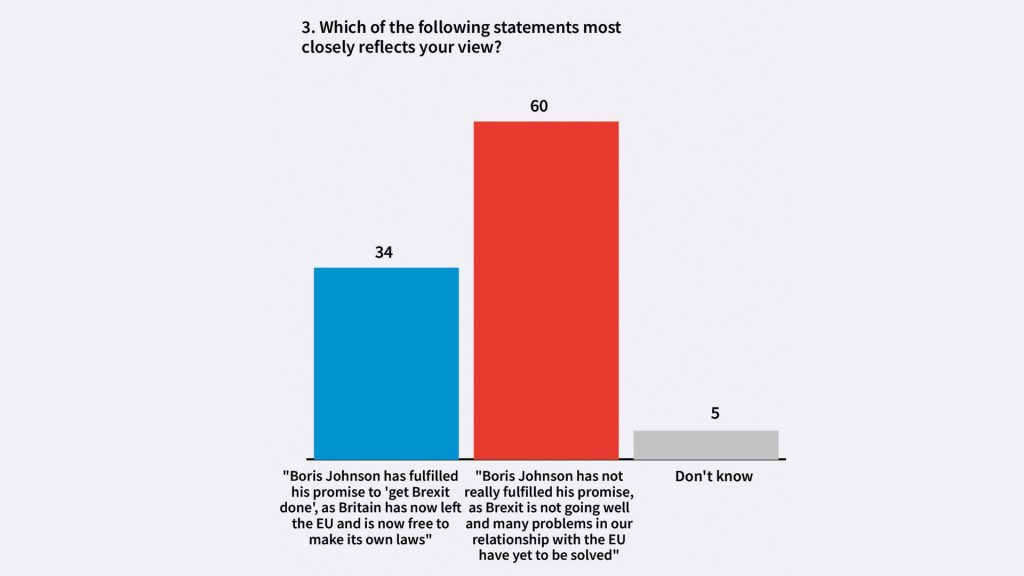

The trouble is that most voters reject his claim. Exclusive research for The New European finds that only one in three voters agree that he has kept his promise to get Brexit done. Johnson insists he did what it said on the tin; six years on, most voters have concluded that underneath the label was a can of worms. Deltapoll offered almost 1,600 respondents two options, reflecting the opposing views of Johnson’s record:

“Boris Johnson has fulfilled his promise to ‘get Brexit done’, as Britain has now left the European Union and is now free to make its own laws”: 34%.

“Boris Johnson has not really fulfilled his promise, as Brexit is not going well and many problems in our relationship with the EU have yet to be solved”: 60%.

As striking as the overall numbers are the views of people who might be expected to accept Johnson’s claim. As many as 46% of Leave voters (that’s more than seven million people), and 41% of those who voted Conservative in 2019 (almost six million) think that Johnson has failed to keep his promise.

These views reflect a growing buyers’ remorse towards Brexit. Paradoxically, this is significant not because voters’ views have changed fast, but because they have changed slowly.

Voting intentions and attitudes to senior politicians tend to move about, sometimes wildly. A party or leader that is up one week might be down the next. This is because many voters have weak loyalties that can easily be changed by short-term factors and ephemeral news events.

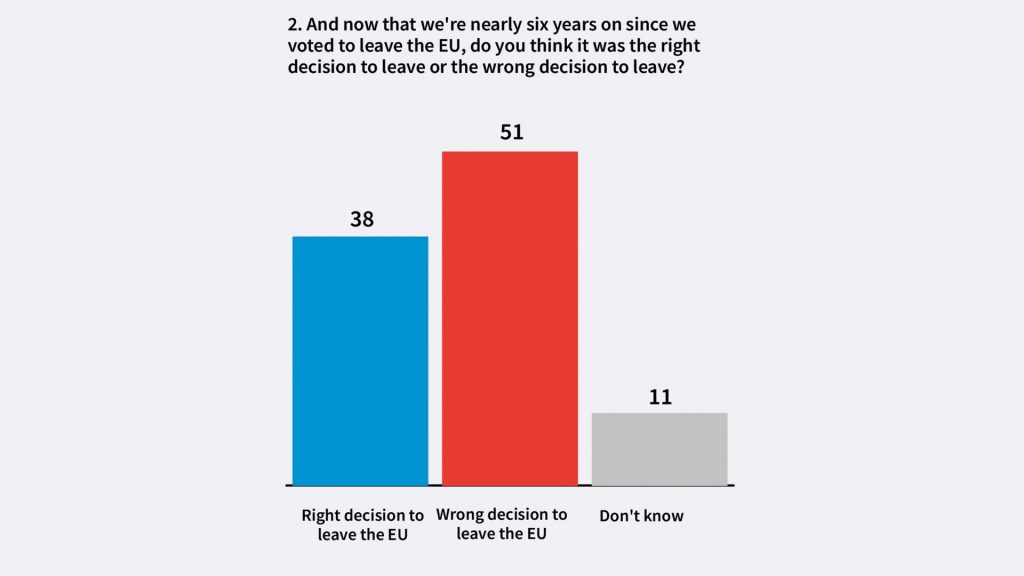

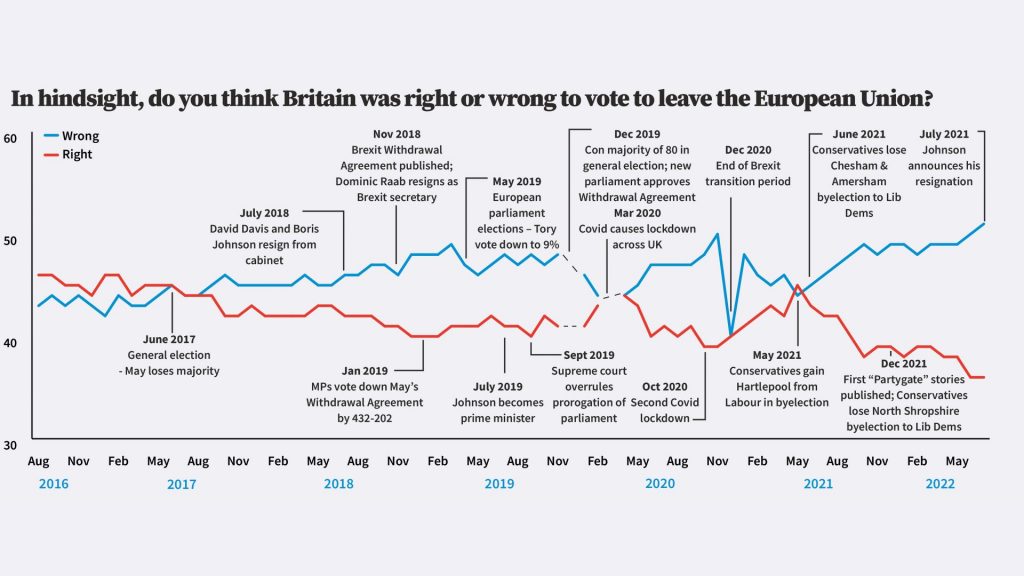

The unfolding Brexit drama over the past six years has not been like that. Since 2016 YouGov has tracked views over whether Britain was right or wrong to vote to leave the EU. The chart shows two things: first, how small the month-by-month movements have been; second, how “wrong” overtook “right” in the autumn of 2017 and has remained ahead in every month except one, April 2020. This was at the start of the Covid pandemic when Britain went into lockdown and Johnson attracted widespread sympathy when he needed intensive care in hospital.

In recent months, “wrong” has moved into double-digit leads, with around 50% saying Brexit was a mistake and fewer than 40% continuing to regard it as a good idea. Given how slowly public opinion has changed, this looks like a verdict that is as settled as anything ever is in politics. Britain is no longer a pro-Brexit country.

Physics offers a useful parallel. Iron can be easily magnetised, but can equally easily lose its magnetism. Steel is harder to magnetise, but retains its magnetic properties longer. Iron’s magnetivity is prone to vary like a prime minister’s ratings. Mounting disillusion with Brexit has been more like magnetising steel: a slower process, but once done, it has tended to stay done.

That said, eight in 10 voters hold the same view as they did in 2016 on the basic issue, in or out of the EU. In contrast, only six in 10 people say they would now vote the same way as in the (far more recent) general election of 2019. The other four in 10 would now choose another party or don’t know how they would vote.

But that eight-in-10 figure for consistency conceals an important difference between Remain and Leave voters. These are the figures from the TNE/Deltapoll survey:

Among Remain voters; right to leave the EU: 8%, wrong 85%, don’t know 6%.

Among Leave voters: right 76%, wrong 16%, don’t know 8%.

YouGov has found a similar pattern: the reason why “wrong” now enjoys a clear lead over “right” overall is because Remain voters are more solid. Among the minority who have changed sides, remorseful Leave voters now outnumber Remain deserters by two-to-one.

Indeed, if I were a committed Brexiteer, I’d be worried about the prospect of further defections. Compare the 76-16% division among Leave voters on whether Brexit was right or wrong, with the 51-46% division among the same people over whether Johnson has kept his promise to get Brexit done. This means that around four million Leave voters still favour Brexit but say it has so far worked out badly.

What has happened in the past few months to produce these figures? Johnson’s tumbling popularity ratings have undoubtedly played a part. It’s likely that some people who have lost faith in the man will also have lost faith in his most prominent project.

However, of greater and arguably more lasting significance is the combined impact of the war in Ukraine and the current cost-of-living crisis. It has provided a vivid test of the case for Britain to “take back control” in order to protect people from the vicissitudes of events abroad.

The movement in YouGov’s “right/ wrong” tracker suggests that the twin crises have done little to advance the cause of Brexit. Deltapoll has tested the point more directly. It asked:

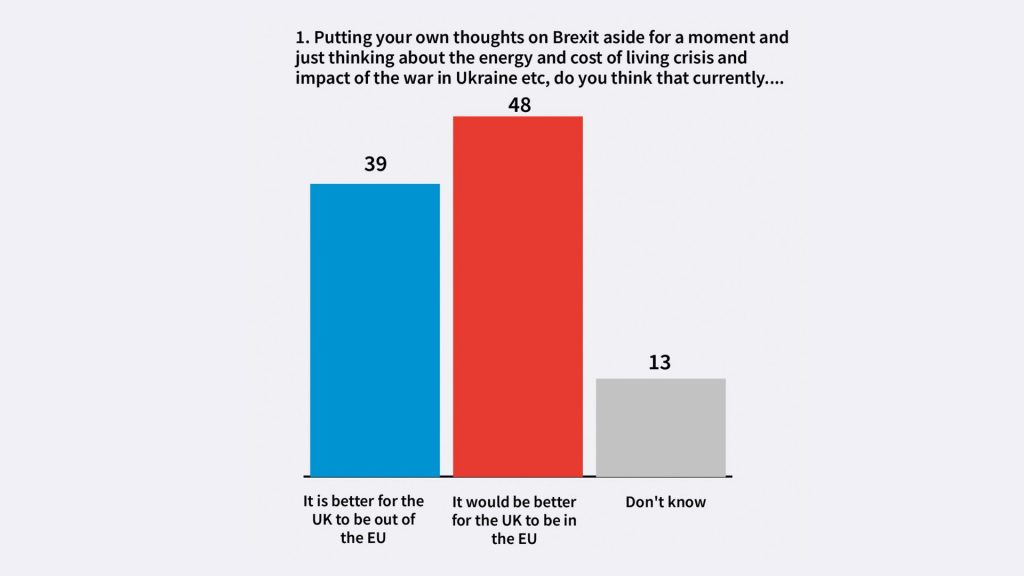

Q. Putting your own thoughts on Brexit aside for a moment and just thinking about the energy and cost-of-living crisis and impact of the war in Ukraine etc, do you think that currently…

It is better for the UK to be out of the European Union – 39%

It would be better for the UK to be in the European Union – 48%

Don’t know – 13%

The public’s verdict is not overwhelming, but the margin is clear. The current crises have persuaded more people of the need for countries to come together than for Britain to rely on its sovereign independence.

All of which might suggest that there are political gains to be made for Labour, seeking to replace the Conservatives at the next election, to campaign for Britain to rejoin the EU. And, indeed, three polls in recent weeks by three different companies, Deltapoll, YouGov, and Redfield & Wilton, all find more people saying “join” than “stay out”. However, the “join” leads are small (six, seven and five points respectively), and there is no prospect just now of either Labour or the Liberal Democrats advocating a new referendum anytime soon.

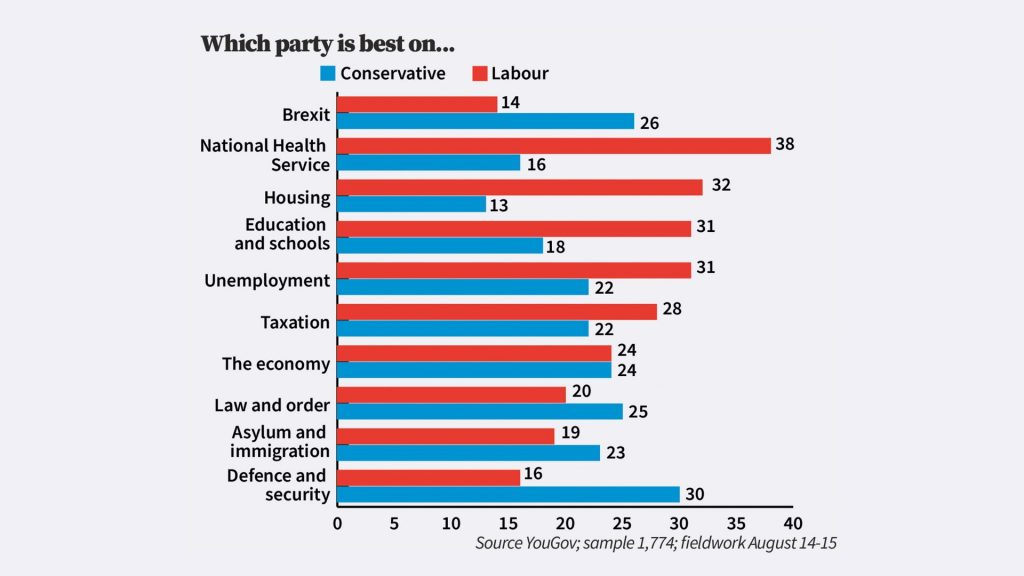

What is clear, though, is that Labour’s ultra-cautious stance on the EU isn’t working. YouGov recently asked people which party they thought would handle Brexit best. Not surprisingly, the Conservative score is poor: 26%. But Labour’s is even worse: 14%. As many as 45% said “none of the parties” or “don’t know”.

To put those figures in context, below are the Labour and Conservative scores on all the issues YouGov tested.

As the figures show, Labour’s score on Brexit is worse than on any other issue. Its failure is all the more striking in the light of its successes elsewhere. It has caught up with the Tories on the economy, and overtaken it on taxation (as well as sustaining its traditional lead on jobs, schools, housing and the NHS). It’s not as if Labour these days is seen as hopeless across the board. It has a particular problem persuading voters that it has got Brexit right.

Drilling down into the figures we find that Labour leads among Remain voters, but only with 21%, against 12% for the Tories. Among Leave voters, the figures are more decisive: Tories 46%, Labour 8%. Labour has irritated many pro-Europeans while failing to persuade more than a small minority of pro-Brexit voters that it knows the right way forward.

Should Labour care about these figures? It seems to be hoping that the next election will be won if it can shut down Brexit as an election issue, exploit its traditional lead on public services, and prevent the Conservatives regaining their usual advantage on taxation and the economy.

It’s not a stupid plan. If Brexit is the dog that doesn’t bark at the next election, there must be a very good chance of Labour winning enough seats for Keir Starmer to become prime minister at the head of a minority government. But if Brexit does start to matter as the campaign unfolds, then Labour’s manifest weakness on the subject might cost it dearly. If just a few Remainers decide that Labour’s stance is so weak that they decide to vote Lib Dem, Green, SNP or Plaid Cymru – or not vote at all – then this could make the difference between a fragile, short-lived Starmer government and a sustained period of Labour rule.

This summer the public mood has shifted: is it time for Labour to shift with it?

Peter Kellner is a journalist, former BBC Newsnight reporter, political commentator and former president of YouGov