In our democratic age, no monarch could survive a determined push by voters to dispense with the royal family. Bearing that in mind, what is the state of public opinion – and should it worry the new King?

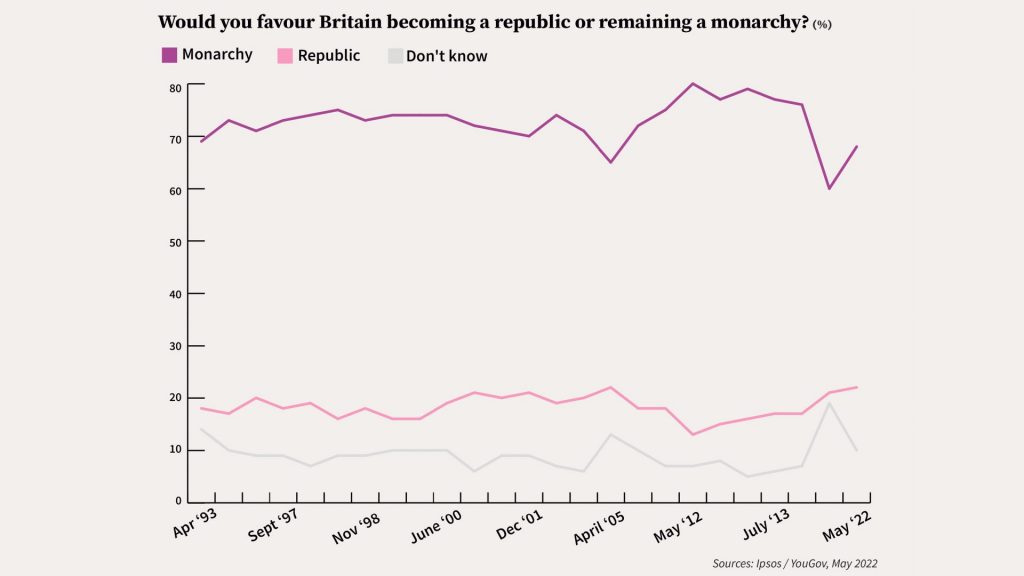

At first sight, the figures suggest he has nothing to fear. For three decades, Ipsos (formerly Mori) has been tracking public attitudes to the basic question: would we favour Britain becoming a republic, or remaining a monarchy? The largest number favouring a republic has been 22% – and the smallest number favouring a monarchy has been 65%. On average there has been a four-to-one preference for the status quo. Support for a monarchy was highest in May 2012, during the Queen’s diamond jubilee, when the margin was six-to-one (favouring monarchy: 80%, republic 13%).

The latest Ipsos figures, from this May, are at the lower end of support for the monarchy (68-22%), but within the mildly oscillating 30-year trend.

There are, however, two clouds that intrude on the seemingly clear blue sky. The first is that views vary by politics, age and ethnicity.

The latest Ipsos figures show that while Conservative voters favour a monarchy by an overwhelming 94-4% margin, Labour voters are more divided: a majority, 59%, favours a monarchy but as many as 32% would prefer a republic.

The royal family endured various crises during the Queen’s reign. If any erupt during the King’s, he should hope that they do not occur when Labour is in office. It’s not that Keir Starmer or any likely successor will seek an abdication, but in some circumstances they might face pressures within their party that they could struggle to contain.

Over-65s back a monarchy by 10-to-one (83-8%), but under-25s divide evenly (monarchy 41%, republic 42%). This is one of those issues where we might expect voters to acquire more traditional attitudes as they grow older; but if today’s young republicans retain their current views, then as time goes by and older voters die out, then the overall figures could show a steady decline in support.

Britain’s ethnic minority voters contain a plurality of republicans, who outnumber monarchists by 47-38%. Again, we cannot be certain whether people will maintain their current views; but if they do, then as the ethnic composition of the UK continues to change, so will the overall figures for the electorate as a whole.

The second cloud on the King’s horizon concerns the cause(s) of Britain’s continuing monarchist majority. The length of the Queen’s reign means that public views are inevitably coloured by her personal popularity.

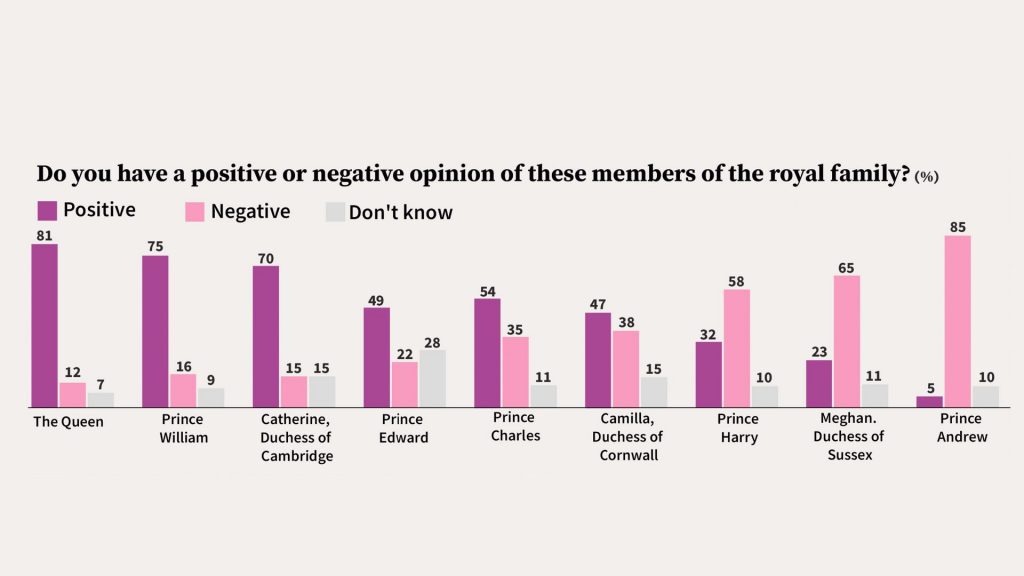

This was always high – and much higher than that of Prince Charles, as he was. The table shows YouGov’s final figures for the main members of the royal family before he became King.

We can safely assume that the Queen’s popularity enhanced that of the monarchy, perhaps by a lot. And the new King’s elder son and daughter-in-law’s high ratings will have done it no harm. However, his and his wife’s ratings are another matter.

As with the monarchy-versus-republic question, we find a generational divide, with voters over 65 dividing almost three-to-one in the King’s favour (72% positive, 26% negative) but under-25s dividing more than two-to-one against him (20-47%).

That said, Charles’ overall rating is still clearly positive. Politicians would envy his popularity. But the comparison with his mother and his son should give Charles pause for thought. An Ipsos poll conducted in May helps to explain his relative weakness. It gave respondents a list of 16 attributes and asked them to pick “all that apply” to each member of the royal family. These were the top three for each of the major royals:

Queen Elizabeth:

Traditional; A symbol of what is good about Britain; Good representative on the world stage.

Prince Charles:

Traditional; Out of touch with ordinary people; Good representative on the world stage.

Prince William:

Good representative on the world stage; Modern; Capable.

It’s not that these results are all bad – all were thought to be good on the world stage – just that Charles’s reputation is not as strong as that of his mother and son. He is regarded as out of touch; William is seen as modern and capable.

This is why some polls, which were conducted while the Queen was still alive, showed that more Britons wanted William to succeed her. A Deltapoll survey last year detected a big difference: William 47%, Charles 27%. YouGov, asking a slightly different question, found a narrower gap: William 37%, Charles 34%. But a further 17% said “neither – there should be no monarch after Elizabeth II”. If we add the figures for William and “neither”, then 34% said they wanted Charles to succeed the Queen, while 54% did not.

Doubtless, new polls will be published in the days and weeks ahead; and there must be a high chance that the King will enjoy a honeymoon with the public. However, the issue is not really what voters think this autumn, or even in the next year or two. It will be in, say, five or 10 years’ time, when a track record has been established and polls measure views of Charles’ performance as King rather than early responses to his accession following his mother’s death.

But even then, how much would it matter if a majority of voters wanted him to abdicate, either for William to take over or for the UK to dispense with a monarchy altogether? Much will depend on the intensity of the public mood. Would voters ever be angry in sufficient numbers to demand the King’s departure – or would they express a mild preference, when asked, for him to go but not really regard this as the most important challenge facing the nation?

My guess is that only in circumstances where something went badly wrong would a negative poll rating reflect an existential crisis rather than a murmur of discontent. This should provide Charles with some protection against what, in political terms, would be a “mid-term wobble”.

What, though, if instead of a crisis, there is a sustained campaign in the years ahead to get rid of the monarchy, leading to majority support for turning the UK into a republic?

Here the lesson of what happened in Australia in the 1990s may be relevant. By the 1990s, a long-running campaign had persuaded a majority of Australians that they should choose their own head of state.

A referendum was held in 1999 to settle the matter. Right up to the end, polls found a clear majority in favour of a republic. Yet Australians voted by 55-45% to keep Britain’s monarch as their head of state. The decisive factor was that the referendum asked voters not whether they wanted a republic in principle, but whether they would back a particular plan for choosing a new head of state.

That plan was for the choice to require the votes of two-thirds of the country’s parliamentarians. The idea was that this would lead to a consensual choice acceptable to both main parties. However, many Australians felt that a home-grown head of state should be elected democratically – by a vote of the people. In the end the plan was defeated by the combination of committed monarchists and people who wanted a plan to replace the monarchy, but not this plan.

Any future surge in republican sentiment in Britain is likely to face the same problem. It will not be enough to secure a majority against our traditional arrangements. It will need a majority for a specific alternative. This will not be easy.

All that said, Charles would surely prefer the positive loyalty of the citizens of the UK. Beyond avoiding bad mistakes, what can he do?

One opportunity, perhaps his biggest, is to link two things: his commitment to the environment with his need to increase his support among younger and progressive voters. These are the very people who are most concerned about climate change. He is on their side; he has the opportunity, as King, to get them on his.

The challenge is to achieve this while maintaining political neutrality, and never saying anything that doesn’t have government approval. But while there are limits to what the King can say, there is much he can do.

As Prince of Wales, Charles set an example on his estates, with solar panels, heat pumps and electric vehicles. He had his Aston Martin altered to run on bioethanol derived from surplus English white wine and fermented whey.

As King, Charles will have the opportunity to lead by example on a larger scale. How about making all royal palaces carbon neutral? Being driven only in electric cars? Making long journeys within Britain by train, not plane? Serving meat less often at state banquets? He won’t be able to avoid having a larger carbon footprint than the rest of us – but, equally, he could cut his by more than we can cut ours.

It is likely that the fate of the planet will be decided during Charles’ reign. What could be better than to be seen today, and remembered in centuries to come, as the King who stood firmly on the right side of history?