Donald Trump has imposed a 10% tariff on UK exports to the USA, as part of a punitive shutdown of global trade announced last night. The UK may have got off lightly, compared for example to a 34% tariff on China and 46% on Vietnam. But the first order effects don’t matter. The second order effects could trigger major economic damage to every economy we trade with and our own.

Some people have been mystified by Labour’s refusal to talk tough in response to Trump, and to minimise the amount of punishment we have to endure. I am not: it both makes sense in terms of geopolitics (for now) and is rooted in both Labour and British historical responses to the last time this happened.

In 1930, the US Congress passed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, imposing punitive tariffs on foreign goods. With the financial system already weakened by the Wall Street Crash, it severely tanked world trade.

In response, four major countries – Canada, Switzerland, Italy and Spain – each took punitive measures. Switzerland boycotted US goods, Spain and Canada introduced retaliatory tariffs, while Italy placed a quota on US automobiles.

But America’s two major rivals – Britain and France – refrained from immediate retaliation. Germany, meanwhile, was still economically beholden to the USA through reparations.

Britain was, at this time, governed by a minority Labour administration, which saw moves towards restricting trade as essentially reactionary Tory nationalism. The Ramsay Macdonald government stuck firmly to the liberal principles of free trade, despite a growing lobby on the backbenches – around both the left and then-Labour MP Oswald Mosley – and among the unions, for protectionism.

Instead, Labour launched a flurry of trade missions – to China, Japan and South America – in the hope of replacing the lost US export market. Which failed.

Labour’s deeper problem was that free trade was the economic model British imperial power had relied on for a century. The only viable alternative was the programme advanced by Lord Beaverbrook: “Empire Free Trade” – that is the erection of tariff barriers around the British Empire.

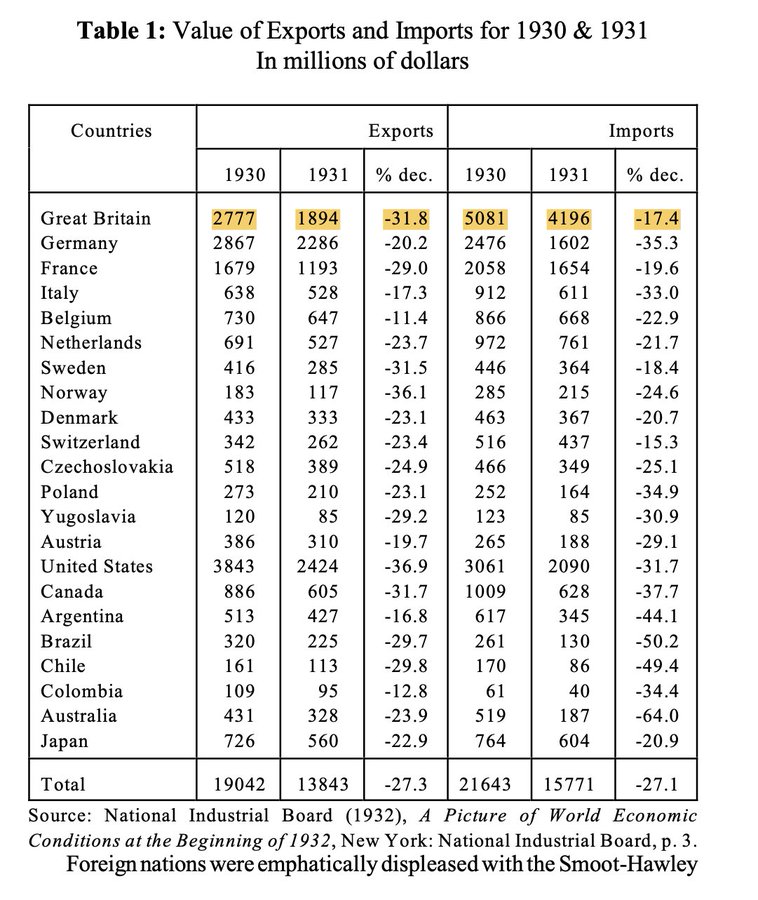

The following table illustrates what happened next. British exports fell by a third in the space of twelve months.

By 1931 the UK was in a trade crisis, because other countries were dumping their goods into its tariff-free space; that put pressure on the pound, which was pegged to gold; that forced Macdonald to go to Washington and Paris in search of loans – and to secure them he pledged to cut unemployment benefits. Neither the unions nor the party could stomach that and the Labour government fell.

And when the fragility of the banking system – from Austria to Wall Street – triggered a second round of financial collapse in 1931, the UK was forced to erect its own tariff barriers. As France did likewise, and Germany went autarkic under the Nazis, global trade values collapsed, deepening the Depression that had originated in the financial system.

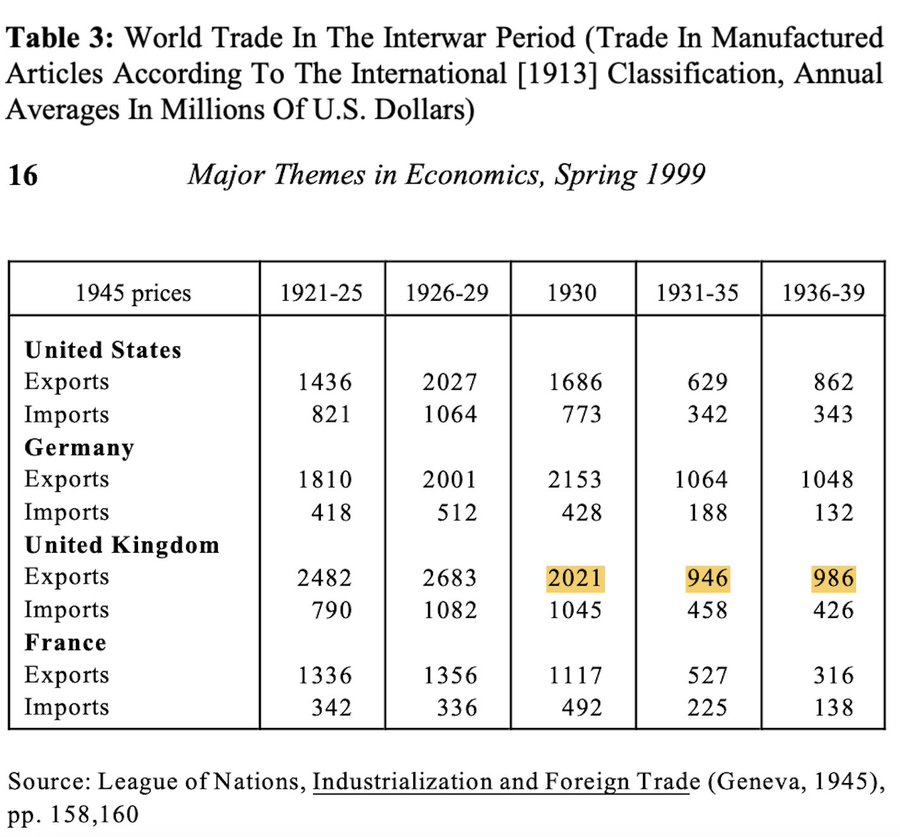

This second table shows the outcome of global trade protectionism for the rest of the decade: the countries that went to war in 1939 had basically stopped trading with each other.

What are the lessons and parallels for today? First off, no matter how economically damaging Trump’s tariffs are, they are part of a much more serious disintegration of the global order. China and Russia have embraced Great Power politics and belittled the rules-based global order.

Trump has declared he will walk away from European security, and a faction in the Trump administration is even seeking a strategic tie-up with Russia, to carve up the Arctic.

The clearest and most present danger is Trump pulling collective defence under the NATO Article V agreement, and pulling the plug on Ukraine, in order to leave it defenseless against Russia.

Second, for now, Europe remains a free and open trading bloc, with the size and heft to take significant retaliatory measures without hurting itself more than the adversary. The 20% tariff imposed on goods from the EU is damaging, but can for now be absorbed.

So in calibrating his response, Keir Starmer is right to avoid needlessly antagonising Trump: the UK – a much diminished economic power compared to the 1930s – should be doing everything in its power to avoid getting hit with tariffs.

But Starmer also has to take account of the fact that Europe is still the UK’s major market, and that if the UK wants to go on playing a leadership role in European security (over Ukraine and collective security) it cannot under any circumstances undermine Europe’s economic response to the tariffs.

Starmer needs above all to heed the lessons of the 1930s. The Macdonald Labour government collapsed because it didn’t understand the world it was living in. It stuck to free trade, flying in the face of demands for protectionism from both right and left, and managed to destroy itself in the process.

When the National Government came off the gold standard, buying precious leeway for economic policy in the face of economic collapse, one Labour backbencher is said to have remarked “We didn’t know you could do that”.

Today’s equivalent would be to fail to consider the retaliatory options in advance, and to understand the radical changes in policy that would be needed should the UK have to join the tariff war.

Because, to put it frankly, 30-odd years of neoliberalism have screwed our economy. We are poor. Our living standards have fallen. Our industry is depleted. Our social cohesion is frayed. We have handed major infrastructure to rip-off banks, foreign investors and private equity firms to see it run into the ground (yes, that’s you, Thames Water, the Post Office, Tata Steel).

It is entirely possible that Trump’s action, together with Chinese, Canadian and European reactions, could tank world trade, triggering both a global recession and a new financial crisis.

It is equally possible that the whole thing is a negotiating tactic. Smoot-Hawley took years to push through Congress and, once passed, was a predictable shock. These tariffs are the product of a mercurial and, let’s face it, unschooled mind, and may be open to negotiation in real time.

But even if the impact is ameliorated, there will be massive reshoring of production to Europe and its periphery. Because just as with nuclear deterrence, once the USA proves itself an unreliable friend, prudence demands its trading partners begin adapting to mercuriality.

At the same time, Europe will be forced to foot the bill for its own defence – including most likely an enhanced nuclear deterrent – and for keeping Ukraine in the fight against Russia.

I have always said that the left should support the Starmer project, over and above what is progressive about it, because there is an unanswered question at the heart of it: what do you do when Plan A does not work?

Labour’s Plan A on growth was to lead with green energy, housing and infrastructure. That will now have to be done with the programme restructured around defence and national resilience, as well as Net Zero.

Labour’s Plan A on security was “Nato First” – to become the leader of a European pillar of Nato by bridging divides between Washington and Brussels. That now looks difficult to achieve – and is exacerbated by the fact that the “Bevinism” that is the underpinning of this stance has for many decades been the single club in Labour’s golf bag.

Labour’s Plan A for Europe was to lead with a security treaty. Now the question of the Single Market will come back front and centre.

It is too early to understand what the full Plan B might have to be, but the danger is that others make it for us.

In Europe, for example, there is talk of a Defence Union; there is already a European Defence Industrial Strategy and we may end up with a European nuclear deterrent. At the trade level, the script Europe has to follow is clear: retaliatory tariffs and reshoring, with the end of softly-softly handling of figures like Musk, and their businesses.

On trade, one solution would be to declare an expanded free trade zone encompassing Canada, the UK, the EU and all like-minded democratic and stable states, which could include parts of North Africa and, at a pinch, Turkey. Over time, if the US position is not reversed, that would cohere a geopolitical bloc around the European Union to match the economic one.

But if new blocs and alliances cohere, it is axiomatic that Britain has to be in them in order to exert leadership.

In the 1930s, Labour managed to destroy itself by misplaying a hand that was – if not strong – stronger than it is now. We are adrift between two continental economies imposing tariffs on each other, one of which has just broken a long-term contract in terms of collective security.

The “old Britain” would have instinctively tried to block the emergence of a Greater Europe project. I don’t think it matters whether we do or don’t today. All we can do is set the terms of it.

To summarise, I am fully behind Starmer’s attempts to minimise tariffs – and they seem to have worked. As in 1930, we can take our time assessing what is real, what impacts are transitory, and where the second order consequences lie.

But if we have to join the tariff war we have to, in some form or other, side with Europe. I cannot see much of our current fiscal and monetary architecture surviving that without big changes to its rules and priorities.

As in the 1930s, we can produce and export our way out of this only in concert with a bigger geographical area. Back then it was the Empire. Today it is Europe. Coming just five years after Boris Johnson promised we would become “Global Britain” – the champion of free trade in a protectionist world – this moment should be one of shame for Johnson and all who backed him.

Trump’s tariffs, brought to us by the same political forces that backed Brexit, show what Brexit was ultimately designed to do: weaken us amid the fragmentation of the global order. The next time Johnson, or Farage for that matter, extols the virtues of being alone in the world, show them the closed car factories that will result from their idol’s actions.

Sources: Milder, Mark (1999) “Parade of Protection: A Survey of the European Reaction to the Passage of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930,” Major Themes in Economics, 1, 3-26. And Skidelsky, Robert, Politicians and the Slump, London,1994