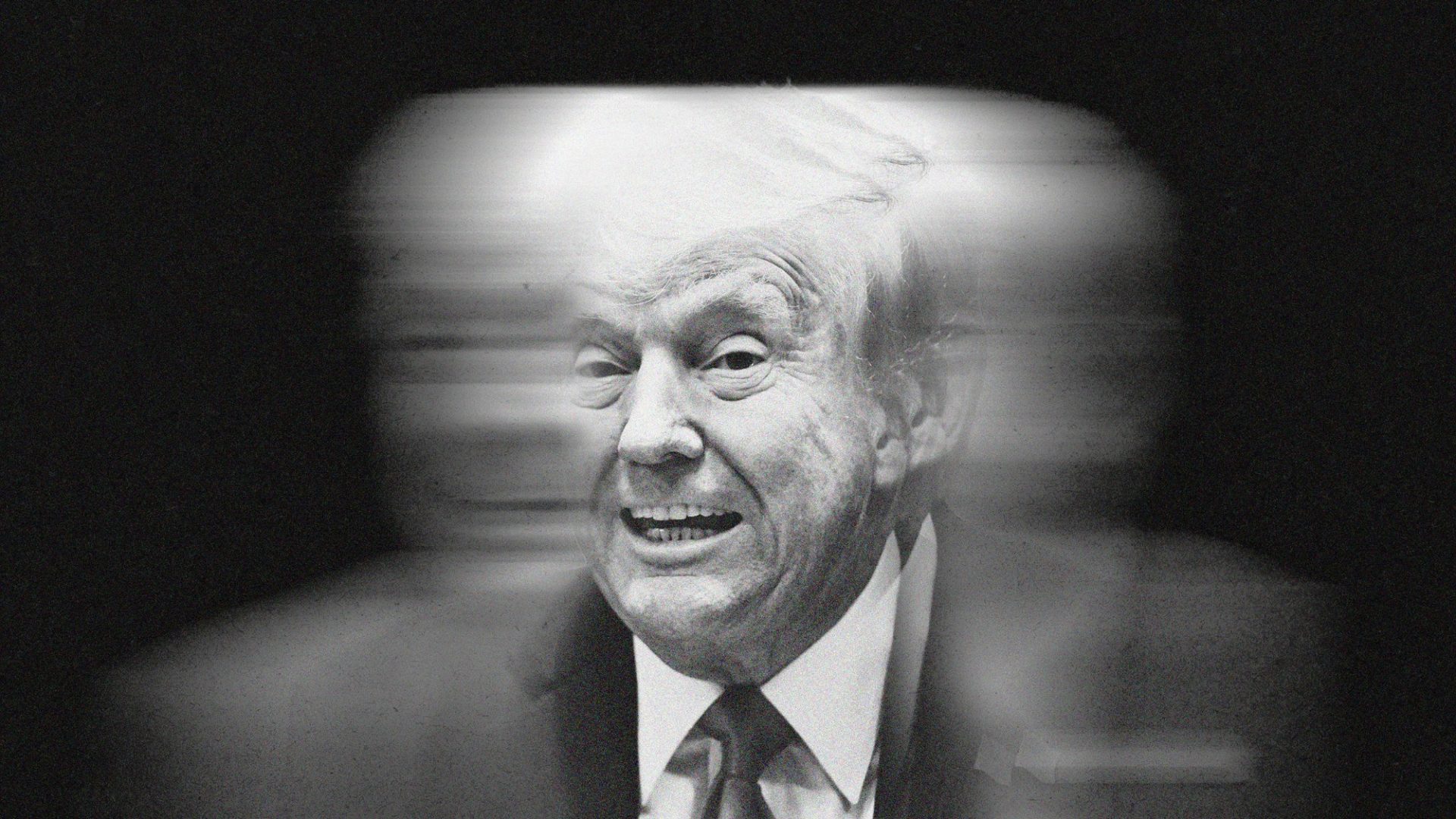

The aftershocks of the blowup in the Oval Office, when Donald Trump and JD Vance attempted to browbeat and humiliate Ukraine’s head of state, are still rocking the foundations of the western alliance.

Not only because it would now fall to them to secure a peace deal in Ukraine, and to front-up any security guarantee to Kyiv, but because what happened to Zelensky could easily happen to any one of them. From Vance’s handshake with the leader of Germany’s far right, to his ludicrous claim that Starmer had silenced free speech, to Musk’s latest tweet calling for the end of NATO, the USA has become a chaos engine in world affairs.

After Volodymyr Zelensky stormed out of the White House, followed by a trail of social media catcalls and invective from key figures in the Trump administration, European leaders were staring into the abyss.

Look beyond the endless psychodrama and narcissism and one fact stares through: the USA is no longer a 100% reliable or predictable ally. Not only is it turning decisively away from conventional deterrence of Russia in Europe. It is not clear on any given day that Trump is committed to the Article V guarantee that stands at the core of the NATO project.

Some fear not only that Trump will attempt to do a deal with Russia over Ukraine over the heads of Europe, but that he is prepared to lose Europe as a strategic ally in order to prise Putin away from Xi Jin Ping.

Faced with this Keir Starmer has achieved a lot, through quiet diplomacy and strategic determination. He has, at least to his own satisfaction, ascertained that Trump is still interested in providing an American backstop to a Ukraine deal. And he has done exactly what he said Britain should do: provide a bridge between Europe and America in world affairs – even if there are people standing at either end of the bridge hurling insults at each other.

But with the Trump administration, traditional diplomacy has become impossible. First and foremost because the administration itself is fragmentary. British diplomats do not believe that Trump’s key subordinates – Rubio, Hegseth or Kellogg – know what the president’s plan for a Ukraine-Russia peace deal is, or whether one exists at all.

Second, because the one consistent behavioural pattern of the Trump administration is passive-aggressiveness: talk nice about King Charles and vote with North Korea at the United Nations. Call Zelensky a dictator and then deny saying it.Starmer emerged from the Lancaster House summit promising to lead a “Coalition of the Willing” to provide a security guarantee for any Ukraine peace deal.

But the ultimate success of such a coalition depends on whether America will provide a backstop. In turn, that depends on finding an answer to the fundamental question – whether the US administration is still morally invested in the defence of Europe against Russian aggression.

Logically, if it is prepared to slap tariffs on its closest allies, slander Zelensky, and practice anti-democratic manipulation in the European political space – what good would its signature on any memorandum be?

And that’s why what matters is what Starmer said in Parliament last week, not what he said in Washington. Labour announced it is hiking defence spending to 2.5% of GDP in 2027, and raising it to 3% in the next parliament. This is as Starmer said a “change in our national security posture”, premised on the realisation that Europe may be left to defend itself.

It was backed up at Lancaster House with a bilateral loan to Ukraine, and the provision of thousands of anti-aircraft missiles. Plus, Rachel Reeves has changed the rules of the National Wealth Fund, allowing money targeted for investment in green energy and infrastructure to be drawn on for co-investment in rearmament. If she executes rearmament decisively, her problem in 18 months’ time will not be stagnation but too much growth.

The Strategic Defence Review, which had been stalled by the Treasury’s unwillingness to fund the new military capabilities needed, has been rolled into a wider Single National Security Strategy – which must now be focused on full-scale rearmament, not just plugging the capability gaps left by 14 years of Tory austerity.

Listen carefully to Starmer’s words: “We will have to ask British industry, British universities, British businesses and the British people to play a bigger part, and to use this to renew the social contract of our nation – the rights and responsibilities that we owe each other.”

That doesn’t just mean stronger state direction of industry. It means universities will be asked to align their scientific research with national security – and to resist those trying to drive defence firms and the armed forces off campus.

It means those members of the Labour NEC still trying to rally the trade unions against arming Ukraine, and blithely appearing on platforms with pro-Putin tankies, will hopefully be told their time is up.

Basically, from schools and universities through to the churches, mosques and temples of our ultra-diverse communities, people are going to be faced with the question: which side are you on? The same question will be asked of those parts of British society that have become enthralled with the Russia-aligned far right.

It will be asked gently at first, because Labour is still essentially a liberal party, with a strong pacifist morality at its core going back to Ramsay Macdonald and Clement Attlee. But when Starmer speaks of renewing the social contract he means getting every community and every public institution signed up to a project of national defence and resilience.

So whatever happens next in the diplomatic fandango being danced with Trump, this is the start of the British Zeitenwende.

We’ve always taken our defence seriously, but as a society we’ve outsourced it to a warrior caste, whose bizarre rituals and self-absorbed language we were happy to stay away from. Now, as our grandparents did in the run up to 1939, we’re going to have to shoulder the burden ourselves – physically and culturally.

For Starmer this is a make-or-break moment. His stature – and the stature of pivotal politicians like John Healey and David Lammy – has already grown. And the challenge of leading and unifying Britain gives him the golden opportunity to see off the threat from Reform, whose entire pro-Trump and Putin-understanding shtick has blown up in their faces.

In the history books, Britain’s fate in the 1930s is defined by “what the Tories did”: appeasement, non-intervention against fascism in Spain, the Munich Agreement, the Norway crisis and the fall of Chamberlain in May 1940. British history in the late 2020s will now be defined by “what Labour did”.

Did they revive political cohesion and democratic resilience, bringing the Tories round to a project of national unity in the face of the disintegrating global order? Did they pull sections of the working class back from the magnetic forces of racism and xenophobia? Did they convince a troubled group of young men, ensnared in online misogyny and radicalisation, that defending Britain is more important than defending Andrew Tate?

Did they bring the unions, the left and millions of their own Muslim voters round to support for British resistance to Putin’s imperialism? And above all, did Starmer align British rearmament with the process now under way across Europe, offering massive economic and social upsides here if he gets it right?

As the European leaders head home from Lancaster House, those are the questions that will define how history sees the Labour leader.