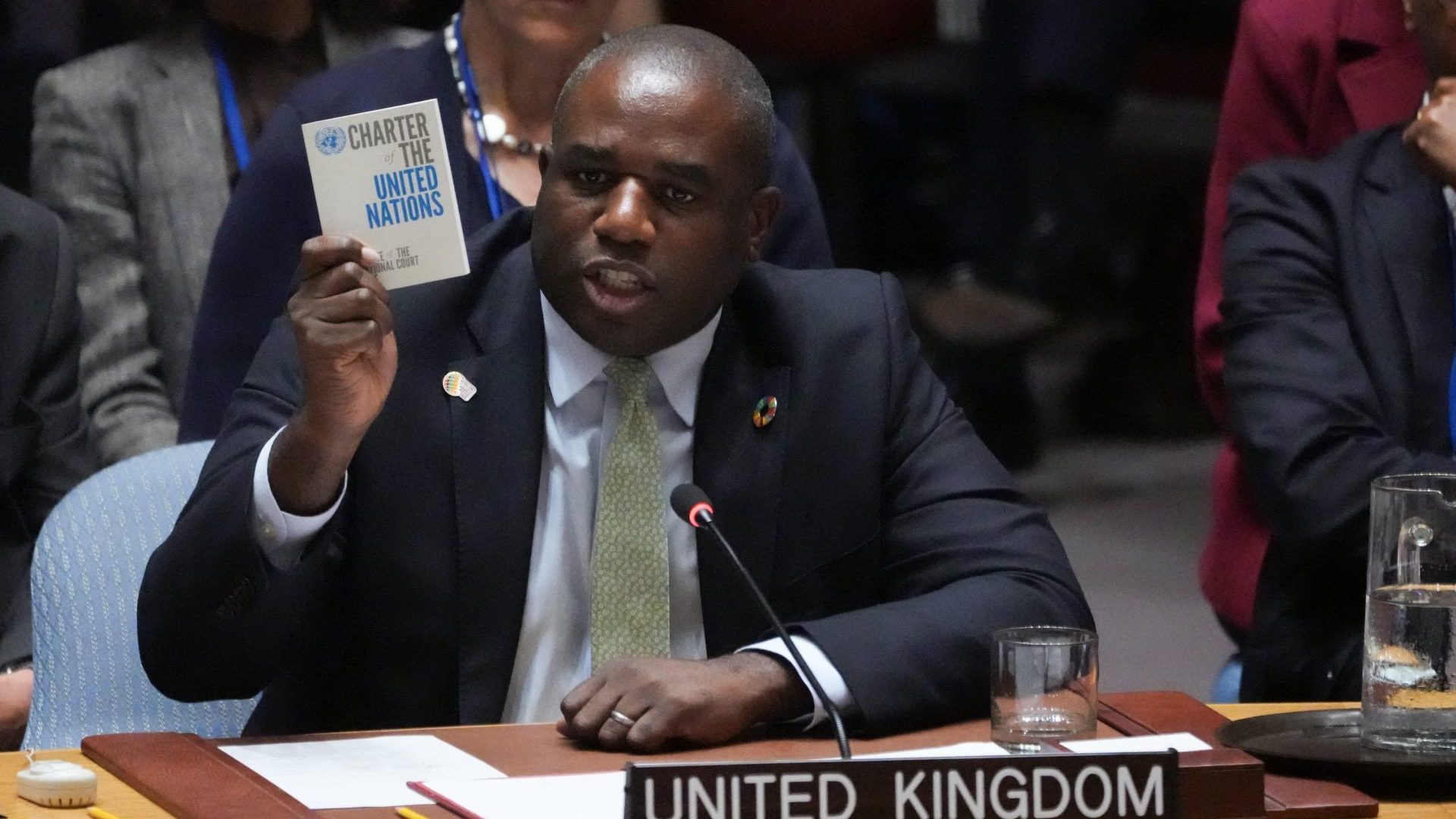

“Your invasion is in your own interests, yours alone,” the foreign secretary, David Lammy, told Vladimir Putin at the UN security council last week: “To expand your mafia state into a mafia empire. An empire built on corruption.”

Putin wasn’t there, of course. But the world was listening. Because it was not only Lammy’s language that broke new boundaries. It was the persona of Lammy himself.

“I speak not only as a Briton, as a Londoner, and as a foreign secretary,” he said. “I stand here also as a black man whose ancestors were taken in chains from Africa, at the barrel of a gun, to be enslaved, whose ancestors rose up and fought in a great rebellion of the enslaved. Imperialism. I know it when I see it. And I will call it out for what it is.”

Sitting around the table were leaders from Guyana, Ecuador, Algeria, Mozambique and Sierra Leone – global south countries used to hearing British diplomatic flummery from the mouths of white Etonians, not straight talking by a black man from Tottenham.

It was an unabashed play for the sympathy of the global south, many of whose leaders have remained equivocal about support for Kyiv, and who have looked askance at western withdrawal of aid to Gaza.

Lammy’s words were, simultaneously, a defence of the west and an acknowledgement to the billions of impoverished people in our former colonial empires that the west was built on their ancestors’ misery. Not long after he finished, his Polish counterpart, Radek Sikorski, bounded over and slapped him on the back.

I was, at that moment, proud not only to be British but to be a member of the Labour Party. Because mobilising the memory of a Guyanese slave rebellion to belittle Putin was just the latest change Lammy has made to the diplomatic weather.

Labour has made much of the crises it inherited from the Tories: overflowing prisons, a broken NHS and a spending black hole. At the Foreign Office, though the wreckage was less tangible, it was no less severe.

There was the legacy of Boris Johnson’s administration, which trashed our relationship with Europe. And the legacy of Liz Truss, who questioned whether the French president was Britain’s friend or foe.

As to the legacy of Rishi Sunak, it was inertia. It was not lost on the diplomatic corps that Sunak spent an hour live on stage with Elon Musk, but could offer only 15 minutes to the president of Indonesia, the most populous Muslim country on earth, who politely refused.

As a result, much of Lammy’s first 100 days in office has been spent on “resets”. The reset with the USA has been about getting physically close to its roving secretary of state, Antony Blinken – in Ukraine, Israel and most recently Paris – while establishing clear diplomatic independence and leverage over Washington.

During the current flare-up between Israel and Lebanon, for example, Britain was the first major power to call for a ceasefire – recruiting France and the USA among 21 other nations to the appeal. From the moment Labour took office it has pushed the USA to allow Ukraine to use western-made weapons more aggressively.

And Lammy also established distance from the USA by pulling Britain’s objections to an International Criminal Court investigation into Israel’s political leadership, by restoring funding to UNRWA in Gaza and by suspending 10% of Britain’s arms sales to Israel.

As a result of this balancing act – combining assertiveness on policy with physical lockstep in shuttle diplomacy – Foreign Office officials say the tempo of calls between Lammy and Blinken has markedly increased.

But the strategic problems facing Labour’s foreign policy are deep and intensifying. Lammy, before taking office, pitched his approach as “progressive realism”: a mixture of Ernest Bevin and Robin Cook, he would be realistic about the fragmenting world order, but still prepared to pursue the ethical dimension of foreign policy.

Lammy’s team will no doubt see the efforts of the past week – topped off with a face-to-face meeting with Donald Trump, whom he had called a “woman-hating, neo-Nazi sympathising sociopath” – as progressive realism in action. But in an era like ours, the spirit of Bevin is always going to have the upper hand.

Labour’s strategic task, which Bevin templated in the postwar period, is to keep the USA invested in the defence of Europe. That was easier to achieve when Russia was perceived as the primary threat. Now that both sides in Washington are focused on China, it is much tougher.

Lammy’s solution has been not just to address the problem head-on, but to use diplomacy with Europe and the global south as workarounds.

Above all, through interventions like the slavery speech at the UNSC, he is not just telling Britain’s story to the world, but a story about the modern world to Britain. Acutely aware of the political, cultural and economic energy coming out of the global south, he is speaking to it on behalf of a progressive, multi-ethnic and religiously diverse UK.

In the end, however, Britain remains a middle-sized power that has inflicted massive self-harm through Brexit: a country that, even as the world was fragmenting into economic power blocs, chose to cut itself off from the one it had spent 40 years building.

Setting that right, through a comprehensive security treaty with the EU and a restored diplomatic alignment with Europe in world affairs, is the task against which the Labour government will be judged. Despite the back-slap from Sikorski, Lammy will need to brace for the ruthless horse-trading that will begin once the foreign ministers of certain other countries get their game on.