During the later decades of the 20th century, traditionally stable Chile descended into political polarisation and violent authoritarianism. This clash was encapsulated by the title of Pamela Constable and Arturo Valenzuela’s landmark book about life under General Augusto Pinochet, A Nation of Enemies.

Chile returned to its more customary calm after the peaceful removal of Pinochet in 1990 and the remarkably successful transition to democracy that followed. But a failure to tackle underlying problems of inequality, poor public services and elite cronyism while the going was good has put it at grave risk of becoming dangerously divided again.

This danger was exemplified in the recent presidential election, which culminated in a December run-off between the hard-left candidate and former student protest leader, Gabriel Boric, and the extreme right winger José Antonio Kast. As the latter said during the campaign, “two models for the nation” were going head-to-head.

In the end, Boric won, becoming the country’s youngest president-elect at 35. But when he takes office next month he will have his work cut out for him as he seeks to deliver on his campaign promises to end destructive inequalities that led to widespread, deadly protests just two years ago.

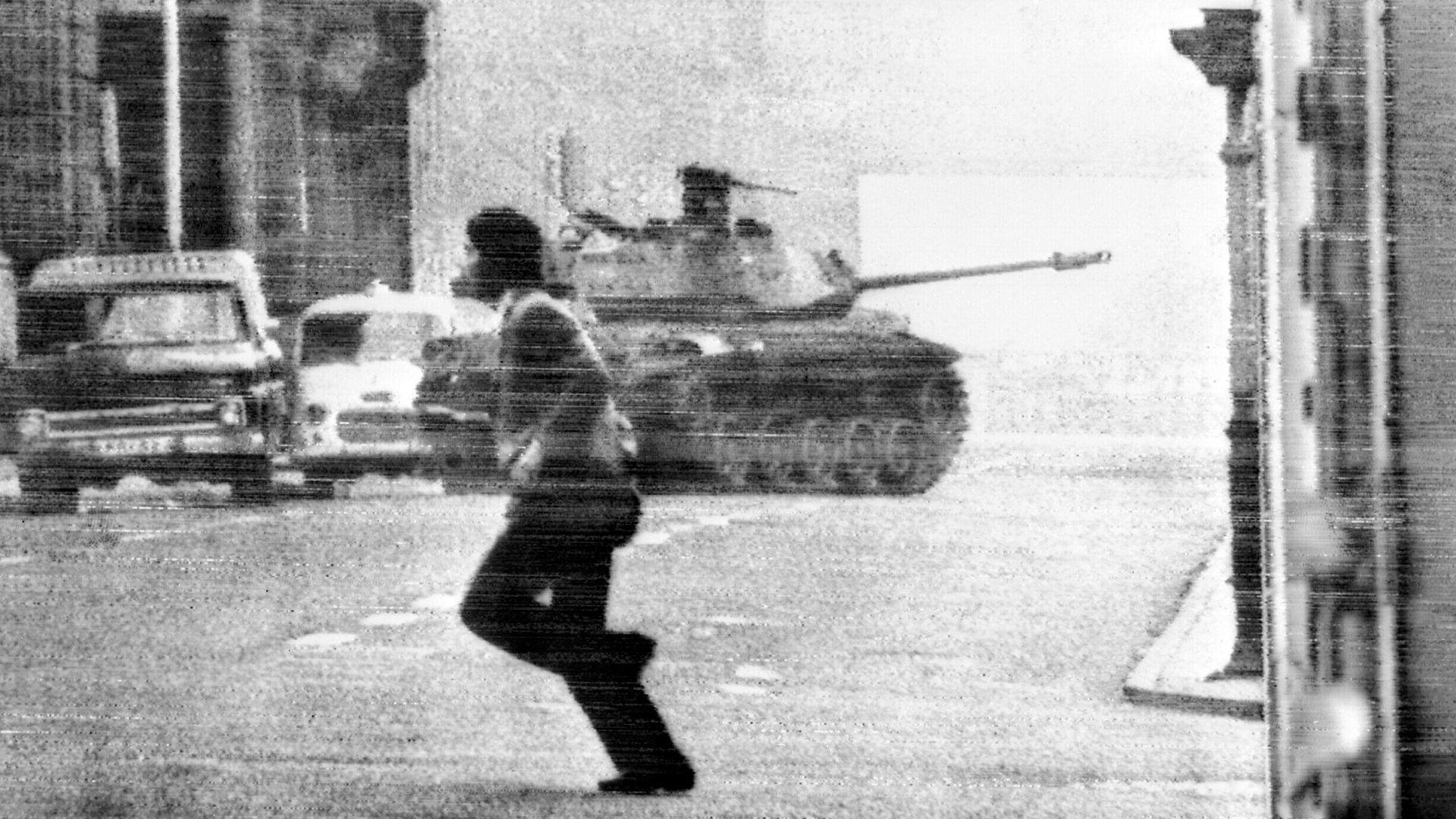

The jarring collision of political philosophies on display during the presidential ballot has stirred memories of the period that led to Chile experiencing the original 9/11 tragedy, when General Pinochet led a military coup against the elected Socialist government of President Salvador Allende on September 11, 1973. To avoid being taken alive by the putschists bombarding the presidential palace of La Moneda, Allende committed suicide in his office with an AK-47 rifle that had been given to him as a present by Cuban leader Fidel Castro.

The Nixon administration, in particular the CIA and the national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, encouraged the coup. This involvement was one of the most controversial episodes of the cold war, with the US prioritising the overthrow of elected left-wing governments in its Latin American “back yard” over its stated commitment to freedom and democracy.

The atrocities committed by the Pinochet regime were among the worst of a notably bloody era around the world. As democracy began to be restored in the early 1990s, a series of official investigations established that the Pinochet dictatorship murdered or “disappeared” at least 3,200 Chileans (the bodies of some victims have never been recovered) and tortured 37,000 more. Grotesque methods were deployed during interrogations, including electric shocks, mutilation, near-drowning in urine and excrement-filled water, and sexual assaults. A further 200,000 people were forced into exile or affected as family members, and an unknown number were held in clandestine and illegal detention centres.

The ageing dictator was finally eased out of power by a combination of brave opponents, reassurances that he and his associates would not face immediate prosecution, and a 1988 referendum in which 56% of the people voted for his removal. Pinochet eventually stepped down in 1990, in return for a lifetime seat in the Senate and continued tenure as commander-in-chief of the armed forces.

In most respects, this return to democracy was one of the greatest achievements of the democratic wave that swept the globe towards the end of the cold war. The transition fulfilled Allende’s words in the final radio broadcast he made to a backdrop of explosions as the coup plotters closed in on him: “I have faith in Chile and its destiny. Other men will overcome this dark and bitter moment when treason seeks to prevail. The great avenues will again be opened through which will pass free men to construct a better society.”

For several decades after Pinochet’s fall, there was almost no political violence and regular peaceful transitions of power took place between respected centre-right politicians, such as the first president after the restoration of democracy, Patricio Aylwin, and centre-left leaders such as Michelle Bachelet, now the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Chile’s economy has also been much more stable than in many of its neighbours. GDP per head tripled between 1990 and 2015 and the country, by most measures, remains the most prosperous in South America.

It can be argued, though, that Chile’s success created complacency among its politicians and elites, causing the steady progress away from dictatorship to stall.

The country’s constitution is still the dubious document devised by Pinochet in 1980 to confer legitimacy on his continued rule. Although there have been more than 20 amendments since then, many Chileans still think this basic law perpetuates a disproportionate right wing influence in parliament and inhibits social reform.

Another major legacy of the dictatorship has been the chronic inequality entrenched by the policies of the “Chicago Boys”, a group of ultra-market-orientated economists Pinochet deployed to run the economy (so-called because they were disciples of the right wing economist Milton Friedman of Chicago University).

Most Chileans accepted these political and economic arrangements as the price of peace and their escape from authoritarianism. But, perhaps inevitably, this situation has proven increasingly unsustainable as new generations with no first-hand memory of the dictatorship, and less fear of it returning, have reached adulthood.

In autumn 2019, mass street protests broke out and some degenerated into riots. Around 30 people were killed and thousands arrested. The ostensible trigger was a small increase in the price of public transport tickets.

But this fare rise was merely the brick that toppled the wobbly Jenga tower of Chilean society. The larger grievances cited by demonstrators included substandard healthcare, inadequate pensions and high university fees.

Above all, the issue is inequality. Chile’s seemingly impressive headline life expectancy of 80 years masks a gap of 17.7 years between women born in the poorest areas of the capital and those in the richest. And a 2018 study of social mobility by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development revealed that it would take the poor at least six generations – if they were advancing at all – to rise to the middle class, which is a very long time by international standards.

The street disturbances finally broke right wing resistance to rewriting the Pinochet-era constitution. This, it was hoped, would open the way to tackling inequality and improving public services.

In a 2020 referendum, 78% voted to draft a new constitution, with the greatest support coming from the young and poorer segments of society. The 155 members of the constitutional body charged with drafting a new text were selected in a further public vote last May, which saw a much lower turnout of 43%. It was hoped that the constitutional review process would redirect political energy from street protests and populism and result in a representative selection of citizens being chosen for the job.

But there have been concerns about the process, particularly among people on the right, who believe many of the constitutional body’s members are inexperienced and left-leaning. Their concerns centre on proposals to impose penalties for “the denial or omission” of past human rights abuses, to restrict Chile’s mining industries, and to limit free speech.

“Not everything will be solved by the constitution but there are many things we must define,” said Bachelet in late December, adding that the final text must create a social and democratic state that can guarantee the rights of all people.

“It would be a grave error not to listen to the wishes of the people. A good constitution is one that helps the country function well,” she said.

The constitutional review has not entirely ended protests or growing polarisation. The discontent has been exacerbated by the Covid crisis.

Frustrations have also been fuelled by political scandals. The billionaire centre-right incumbent president, Sebastián Piñera, survived an impeachment vote last November after being cited in the Pandora Papers investigation over the questionable $152million sale of a mining company owned by his family. Piñera, a former businessman, is one of the richest people in Chile and his elder brother, José Piñera, was one of Pinochet’s “Chicago Boys”.

Some observers have suggested that his escape from impeachment owed more to concerns about the upheaval of removing him than to doubts about the strength of the case against him.

The election itself illustrated how Chile is at risk of slipping back into extreme polarisation. With Piñera ineligible to stand due to term limits, the two candidates in the run-off were the leftwing Boric, who is backed by the Communist Party, among others, and Kast, whose most memorable claim was that if Pinochet were still alive “he would vote for me”.

Kast won 28% of the vote in the first round, compared with Boric’s 26%. But Boric ultimately triumphed in the run-off, securing 55.87% by convincing more supporters of the eliminated candidates that he would be the lesser evil. Kast, to his credit, was magnanimous in defeat, writing that his opponent “deserves all our respect and constructive collaboration. Chile is always first.”

It remains to be seen, though, if all of Kast’s backers will support his position if and when Boric attempts to fulfil his pledges to increase taxation significantly and expand the threadbare welfare state. In an ominous echo of the Allende years, there are serious concerns that Boric will struggle to retain the acquiescence, let alone support, of partisans from the other side. None of which bodes well for obtaining the essential political consent for the changes Chile badly needs or restoring an economy battered by Covid.

In an open letter to the country before the election, Boric said his government would make the changes demanded in the 2019 uprisings.

Robert Funk, a political scientist at the University of Chile, says the main political division in Chile today is generational; “between the generation that was born into democracy and the older generation that lived through the coup d’état, the dictatorship, the transition to democracy, and learned certain lessons”.

Much responsibility for steering the country through this challenging period will now fall on the substantial segment of the population and its political representatives who remain committed to finding compromise.

Their presence means Chile is still some way from sliding back into being a “nation of enemies”. But, as the writer and psychologist Marco Antonio de la Parra told the authors of that book after the fall of Pinochet, “the fear may have lessened now, but how little would it take to bring it back?”