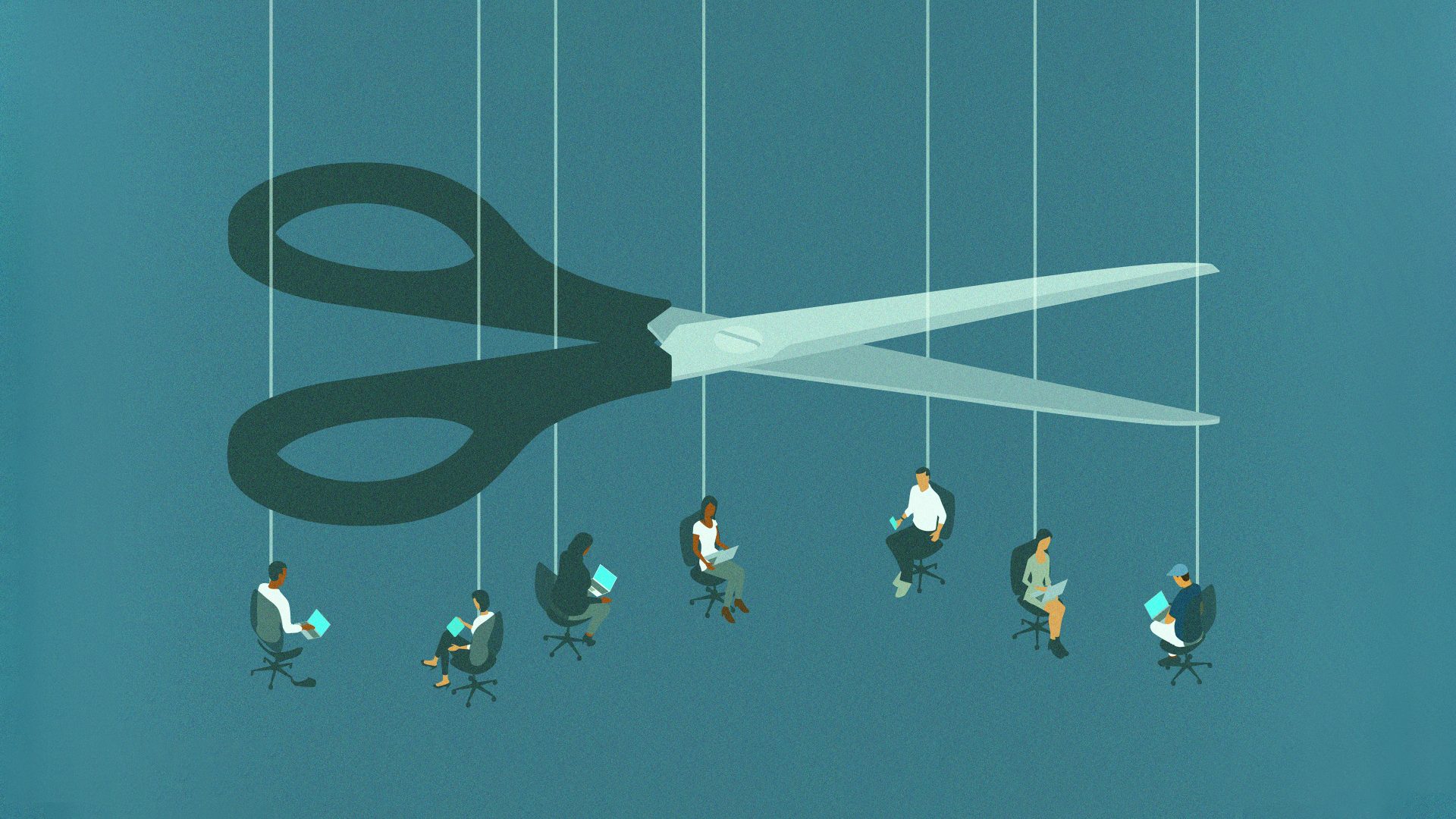

Bureaucrats seem to breed at a rate that would impress even the most rampant of rabbits. Even though technology has been lessening the need for humans to do much of the drudge work involved in running the country, the numbers employed by the government continue to rise. At the end of last year, the Resolution Foundation estimated that, by 2030, almost a fifth of all workers would be employed by the state.

Governments regularly declare that they will slim down the bloated bureaucracy, but public-sector flab proves hard to budge.

Now it seems that the health secretary, Wes Streeting, is really determined to cut the numbers employed in running the nation’s health services and, after eight months in the job, he has concluded that the only way to do so is with a scythe, not a scalpel. He is abolishing NHS England, the largely independent organisation that sat between ministers and front-line NHS operations. His reasons show how the UK’s enthusiasm for creating tier upon tier of administration can lead not only to a costly job creation exercise, but also stifle effective decision-making and productivity.

Streeting claims that he tried to find a way of making the structure he inherited work, but the duplication of effort and the second-guessing that went on between the Department of Health and NHS England made it impossible. His decision will eradicate at least 9,000 jobs and will give more direct control to the government, which is ultimately responsible for the NHS. The reduction in numbers is small compared with the armies of people working in the health service, but those leaving will never have come close to an actual NHS patient: it is administrators who will be leaving.

The structure Streeting is dismantling was the vision of a Conservative health minister, Andrew Lansley, who was only in charge between 2010 and 2012. Bureaucracies, though, often outlast the politicians who create them.

The UK’s departure from the EU created a genuine need for new government functions, but the growth in numbers has gone far beyond that. According to the Office for National Statistics, employment in central government hit a record last year, at 3.9 million, with 6.1 million employed in the public sector as a whole.

Many of these people work hard and do important jobs, be they doctors, teachers, cooks or cleaners. A growing proportion of civil servants, however, are simply administrators. It seems that, as technology has lessened the need for clerical assistants and telephone operators, the need for people to administer what the machines do has grown. What Streeting has found in health is, one suspects, being mirrored in many parts of the public sector.

As the chancellor, Rachel Reeves, pursues her increasingly elusive growth agenda, she has hit on the planning laws as one area in which unnecessary hurdles cause lengthy delays and prevent, in particular, much-needed housing developments from proceeding. The finger of blame is generally pointed at the public, the “nimbys” who do not want any new development in their area. But the planning process itself can be ludicrously complicated, with various government agencies able to intervene.

Keir Starmer has enraged environmentalists recently by citing the case of an offshoot of Defra that in effect stopped the development of more than 1,000 homes because of the presence of a colony of jumping spiders on the site. It was, he indicated, the sort of anti-growth behaviour his government was keen to stop.

A flexible approach to such an issue would surely have allowed the spiders to be accommodated without preventing the development, but flexibility tends to be incompatible with tiers of administrators.

The dual structure that had been created to oversee the health service means that removing unnecessary layers of personnel is relatively straightforward. In other sectors, the fat may not be so easy to eliminate, but it will undoubtedly be there and, in her quest for cuts, Reeves needs to find it. The numerous organisations that are known as “arm’s length public bodies” might be a good place to start. The soon-to-be-defunct NHS England is the largest, but there are more than 300 of these theoretically independent organisations that are entirely government funded. They include HM Revenue & Customs, the Environment Agency and the DVLA (Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency).

Of course, they may each be as slender and efficient as it is possible to be, but can we be sure?