The eyes of Europe are once again on Paris as a blockade by disgruntled farmers threatens to “lay siege” to the French capital. Progress in the dispute is being watched keenly by those planning the city’s hosting of the Olympic Games, which begin in just under six months’ time, with the Paralympics following a month later.

The world has been told that these Games, held a century after Paris hosted in 1924, will be like no other. It is not just the scale of the event – 13 million spectators flocking to see 15,000 athletes competing in more than 1,000 contests across 54 disciplines – but that the city itself will be an integral part of the action. Several of its most iconic landmarks are being integrated into the events, from the area around the Eiffel Tower to the Grand Palais and even the Seine.

And, for the first time in the history of the Summer Olympics, the ceremony will not be held in a stadium but in the heart of the city, with the parade of athletes travelling by boat along the river. Also, if all goes to plan, 500,000 spectators will be able to attend – around 10 times more than a traditional indoor event – and many of them will pay no admission price.

Tony Estanguet, president of the organising committee, told the New European that he wanted to put on “a spectacular Games”, one that goes “out of the stadiums and into the city, using our iconic landmarks.”

His aim is also to make the Games more accessible, and more mobile. “The programme is very much a national one,” he says, “with several cities hosting competitions, and the torch relay taking in 60 départements and 400 towns and cities,” adding that, so far, “we have sold more than 7.5m tickets.”

Yet in France, mere success will not be enough. The country, ever politically fractious, seems more divided than ever. The scale of the farmer protests seem to have taken the government by surprise, but they come after a recent poll that said 68% of voters disapproved of Emmanuel Macron. Marine Le Pen’s National Rally leads in the opinion polls. The capital’s young environmentalists are concerned about the Games’ sustainability and its local communities bemoan disruption and displacement. Those who live elsewhere in the country complain about Paris getting the lion’s share of public funding – again.

The Olympic lead-up so far hasn’t exactly been plain sailing. A test event for the swimming had to be cancelled due to concerns over water quality following exceptional rainfall. Then, more seriously, there was the row over a plan by Macron’s government to persuade thousands of homeless people to leave the capital for other areas – reportedly to ease pressure on accommodation during the Games. Though it has since been claimed that the plan was already in progress, and not linked to the Olympics, it was a stark reminder that the City of Light isn’t always that for everyone.

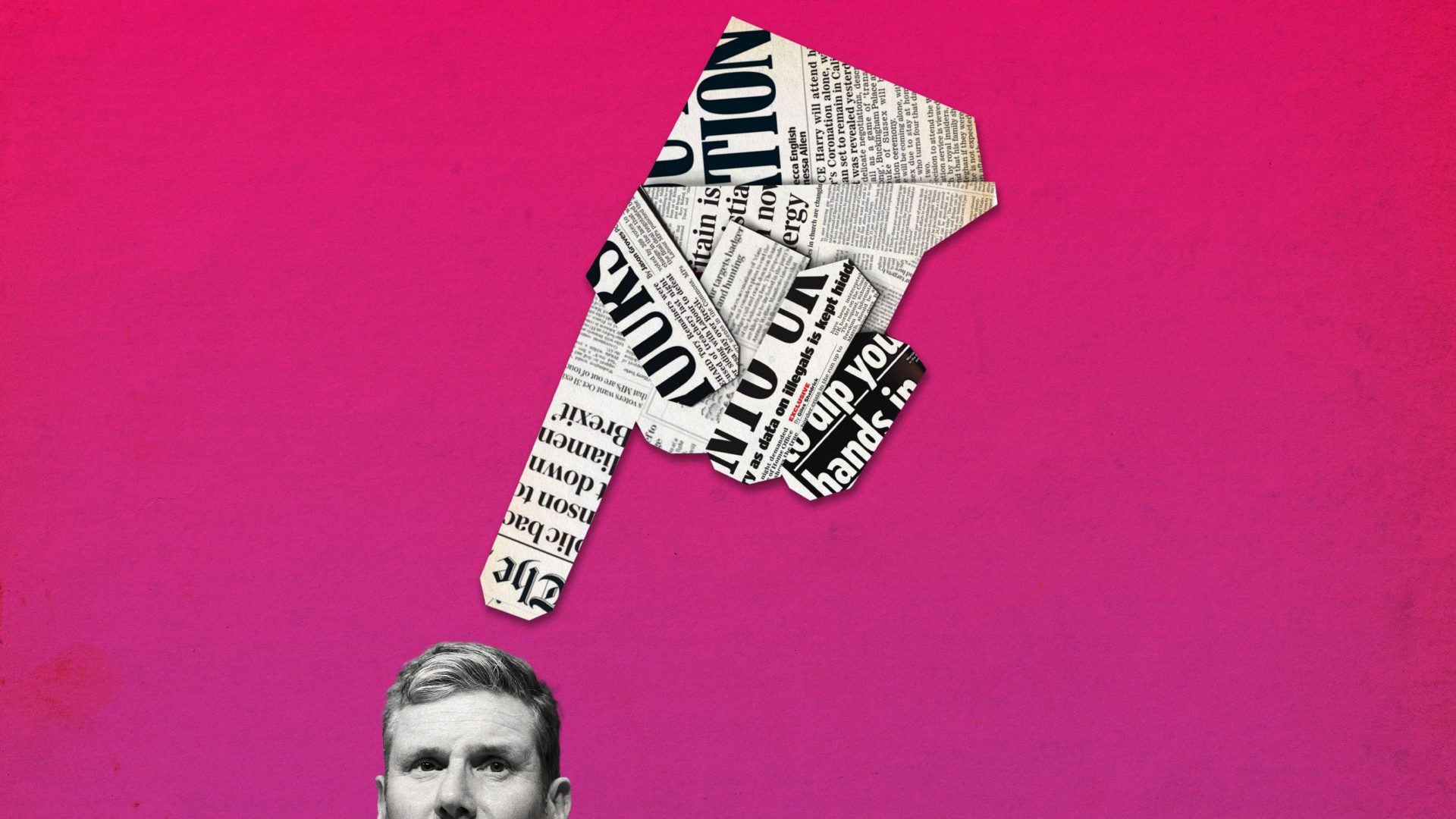

Then another argument broke out over the bouquinistes – the famous booksellers along the Seine – who face the removal of some of their iconic green stalls for security reasons. A test of this in November sparked outrage. While organisers have pointed out that it would only be for the period of the opening ceremony, rather than the full duration, others argue that they shouldn’t have to leave, full stop.

And that’s not all. From complaints about high ticket prices and concerns over civil unrest and/or strike action to the hysteria around bedbugs in the city’s hotels, it has felt like one thing after another for Paris’s residents. And towards the end of the year, to add to all this pre-Olympic angst, the terror alert in France was raised to the highest level, followed by a series of hoax bomb threats and the killing of a German tourist by a French national Islamic State sympathiser in a knife and hammer attack close to the Eiffel Tower in December.

The security operation at the Games will be huge, with 20,000 stewards recruited from local communities joining 22,000 private security guards, tens of thousands of police officers and thousands of soldiers. Organisers are confident that for potential spectators, perceived risk will not outweigh the appeal of being part of one of the world’s greatest sporting events.

“Paris is a city that keeps proving extremely resilient and able to reinvent itself,” says Corinne Menegaux, managing director of the capital’s tourist office, now known as Paris je t’aime. “This is especially true for the tourist sector. We have proven many times that the travel desire for Paris stays strong and that visitors come back as soon as they can.”

Meanwhile, to answer climate concerns, the carbon footprint of the event will be reduced by 50%. Almost all of the venues will be existing or temporary structures, which will minimise the environmental impact. All will be accessible by public transport.

To prevent populists from claiming the Games are just for the metropolitan elite, there are efforts to involve as much of the country as possible – including, notably, the suburbs of Paris. For example, Seine-Saint-Denis, one of the less affluent areas to the north-east of the capital, will be the setting for the newly constructed athletes’ village, media village and aquatic centre. Afterwards, the two villages will be used as housing, and around 20 sports facilities will be renovated for the benefit of the local community.

“It’s allowing everyone to appreciate the scale of the Games – and the scope of what the Olympic legacy will be for the territory,” says Olivier Meïer, director of Seine-Saint-Denis Tourisme. “There remain strong expectations from the local population that these games are truly theirs. That the Olympic celebration is also that of the inhabitants,” he said, “and that the economic benefits are equitably shared.” Countrywide legacy projects include 30 minutes of daily exercise in primary schools, free swimming lessons for adults and children in temporary pools and more help for local sports clubs.

Despite the misgivings, a recent poll showed that 71% of French people have a positive opinion of the Games. Plus, the majority believe that the event will be beneficial to the country: for economic activity (65%); for its image abroad (59%); and for the promotion of physical activity and sport (65%).

In fact, such has been the surge in enthusiasm, there are now concerns over whether Paris has sufficient infrastructure to cope with the huge influx – and, in particular, enough places to stay. Renting an apartment in Paris during the Games will not be cheap.

“It’s true that demand is going to be very high,” says Bruno Gerby, general manager of Bloom House Hôtel & Spa. “As well as all the sports fans, there will be the invited guests of sponsors and then the tourists. Overall, though, I think Paris will face it all quite adequately – especially as the number of beds has increased considerably over the past two years.”

Certainly, back at the headquarters of the Paris 2024 Organising Committee, they remain convinced that all is on course. A series of competition test events, some featuring Olympic athletes, have passed off smoothly. But with war in Gaza and in Ukraine, and after the recent attack in Paris, will the Games be safe?

“In terms of security, we started that journey very early,” says Estanguet. “While the police and the military will be responsible for the city and its streets, some 17,000 private security staff will oversee the stadiums. We have a very coordinated task force in charge of security who have been planning for a long time.”

“What is important to remember is that France has lots of expertise in hosting this kind of major sporting event. Over recent years, we have organised large competitions in many sports: the Rugby World Cup; the Football World Cup; the Tour de France; the tennis at Roland Garros; the Paris Marathon.”

Yes, it hasn’t been the smoothest of lead-ups. And yes, the country remains deeply divided politically. Overall, though, watching the preparations unfold, it’s hard not to get caught up in the spirit of it all.

It even looks as if the famed spire of Nôtre-Dame will be in place again in time for the Games – something that many doubted was possible after Macron’s pledge. So, even though the famous cathedral itself will not be open and despite all the fault lines within French society, perhaps this monumental sporting event might, for a few weeks, bring France back together again.

Caroline Harrap is a Paris-based freelance journalist and editor who has written for France Today, the Guardian and Euronews, among others. She is also a co-founder of The Society of Freelance Journalists.