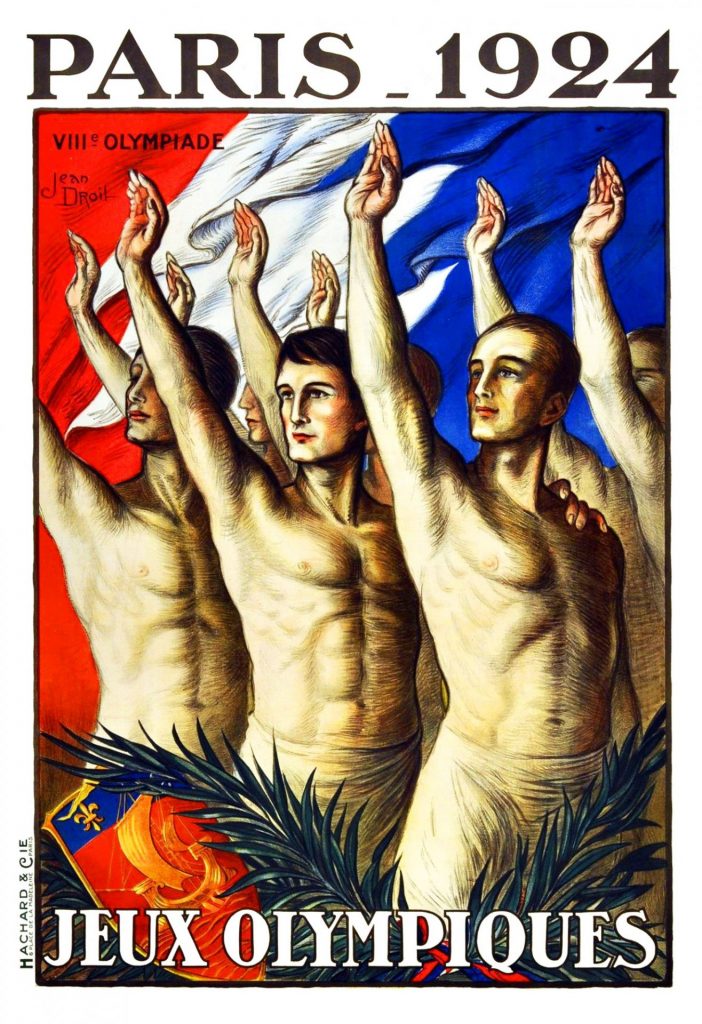

Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the Olympic Movement and president of the International Olympic Committee, first came up with the idea of reviving the Olympic Games back in 1889. By the 1920s, having seen his idea take root, he was ready to retire, and so it was only fit that the Games should be held in his home city – Paris.

And so the seventh Olympics of the modern era got under way in the French capital, running from May to July 1924. The remarkable images on these pages show not only how photography was finally able to capture the drama of sport, but how the Games cementing itself in the public consciousness.

The previous Paris Games of 1900 had coincided with a World Fair in the city, and had been largely ignored. But the 1924 Olympics had a much higher profile – the number of participating nations jumped from 29 in 1920 to 44, and there were 3,000 participants in the field, including 100 women.

The opening ceremony attracted 45,000 people to the Stade Olympique de Colombes on July 5. Pigeons were released, cannons were fired – not at the same time – and the Olympic flag was raised. But despite the “opening” pageantry, the Games had officially begun in May, with a triangular rugby tournament between France, Romania and the US (who won).

The 1924 Olympics have become lodged in the popular imagination for being the basis of events depicted in the film Chariots of Fire, when Harold Abrahams won the 100m final, while Eric Liddell, a devout Christian, declined to run on a Sunday. Liddell later went on to win the 400 metres final in a record time of 46.7 seconds.

In another link to the silver screen, Johnny Weissmuller took three gold medals for swimming. He would famously go on to portray Tarzan in a string of Hollywood films.

On the tennis court, Helen Wills, the American, scooped two golds. Another US tennis player, Richard Williams, was lucky to be competing at all. He had survived the sinking of the Titanic and spent so long in the water that his legs had become frozen. Pulled from the water, the doctors recommended amputation.

“I’m going to need these legs!” Williams shouted, and proceeded to march around the decks of the rescue ship until they had thawed out. In Paris he won mixed doubles gold with Hazel Hotchkiss Wightman.

In the end, the US finished top of the medals table, winning 45 golds, with Finland in second with 14 – the Finnish distance runner Paavo Nurmi having won five gold medals.

Coubertin once said: “The important thing in life is not the triumph but the struggle, the essential thing is not to have conquered but to have fought well”. The games have changed much since 1924, but that ethos remains at the very centre of the Olympic ideal.