Politicians can be strangely reticent when it comes to discussing their reading habits. Angela Merkel is a Dostoevsky enthusiast who reads him in the original Russian. Emmanuel Macron loves the plays of Molière so much he can recite his favourite passages by heart. Rishi Sunak has enthused about his favourite author Jilly Cooper – “she’s done lots of different books,” he revealed to ITV’s This Morning earlier this year.

These out and proud literati are definite exceptions. Modern political figures are actively discouraged from expressing enthusiasm about anything at all for fear of putting their size nines into their own mouths, particularly when it comes to aspects of their lives that risk making them look like actual humans.

This cultural silence is arguably an improvement on how it used to be, when revelations of private passions were workshopped and focus-grouped in advance to produce excruciating outcomes like Gordon Brown and the Arctic Monkeys and the time in 2017 when Theresa May told a classroom full of primary schoolchildren she loved the Harry Potter novels. That was going perfectly well until she was asked to name her favourite character, causing her almost to short-circuit with a pop and the smell of burnt wiring.

“I don’t think I’m similar to any of the characters in Harry Potter,” she said, brimming with the sheer joy of reading, “but they are a great read for adults as well as for children.”

There is one notable current exception to this literary political omertà however – a European leader happy not only to reveal her favourite books but willing to quote them in political speeches. Last month she even opened an exhibition in Rome devoted to her favourite author.

When the Italian prime minister Giorgia Meloni spoke at an event in London in April she concluded a speech in support for Ukraine with:

“I do not love the bright sword for its sharp edge, nor the arrow for its swiftness, nor the warrior for its glory. I only love that which I defend”.

That line was originally spoken by Faramir, son of Denethor, who battled the orcs at Osgiliath in the Two Towers section of JRR Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. It turned up in a political speech by a European prime minister because Giorgia Meloni loves Lord of the Rings like you wouldn’t believe.

This was far from the first time Meloni had cited Tolkien’s work. When in 2008 she became Italy’s youngest ever cabinet minister at 31 under Silvio Berlusconi, she vowed at her swearing-in not to be corrupted by the “ring of power”. Earlier that year she had been photographed for a magazine profile looming behind a sculpture of Gandalf. In her 2021 autobiography Io sono Giorgia she identified Samwise Gamgee as her favourite character, writing, “He was only a hobbit, a gardener, but without him Frodo would never have carried out his mission. As Tolkien wrote, ‘it is the small hands that change the world’”.

With hobbits so high among her most influential political philosophers it was no surprise when Meloni showed up as guest of honour at the opening last month of the exhibition Tolkien: Man, Professor, Author currently running at Rome’s National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art.

Marking 50 years since the English author’s death, the show includes letters, memorabilia and manuscripts, a Lord of the Rings pinball machine as well as art and sculpture by fans and music inspired by the fantasy novels. Leonard Nimoy’s seminal The Ballad of Bilbo Baggins, for example, will definitely be on Meloni’s iPod and is still cooler than the Arctic Monkeys.

On the face of it, Meloni’s passionate enthusiasm for a series of books she first read at the age of 11 might seem a charming quirk that humanises a significant and controversial European political leader. Yet scratch the surface of this innocent pleasure and something much darker lurks beneath.

Italy’s most right-wing leader since Mussolini, Meloni led the Fratelli d’Italia party that she co-founded in 2012 to victory in Italian elections last year on a manifesto expressing hardline policies in areas like immigration and LBTQ+ rights. She has a long history of involvement with extreme right-wing organisations including the Movimento Sociale Italiano, founded by neo-fascist Mussolini nostalgists, which she joined at 15. When the MSI morphed into the Alleanza Nazionale in 1994 Meloni became active in its youth wing, Azione Giovani, and was elected its president in 2004.

Where does Tolkien fit in to this impeccable far-right CV? Since its first publication in Italian in 1970 the Lord of the Rings series has been held up by the Italian right almost as a canonical text. As Meloni herself said last year, “I think Tolkien could express better than us what Conservatives believe in. I do not consider Lord of the Rings to be fantasy”.

Before the 1970s, Lord of the Rings had been loftily dismissed by left-wing Italian publishers as trivial bourgeois escapism, so when the right-wing imprint Rusconi issued the first translation the right took one look at the nostalgically bucolic world of the Shire and the simple binary of the books’ good-versus-evil narrative and heard exactly what they wanted to hear.

Since the second world war, the Italian far-right had struggled to find acceptable flags to rally behind. Traditional fascist symbolism was out, but a simplistic interpretation of Tolkien’s work seemed to permit the discussion and dissemination of ideas and philosophies unpalatable to those who remembered the reality of life under Mussolini.

The books had obvious appeal to the young and in 1977 the Azione Giovani staged its first annual “Camp Hobbit” festival where Italian youths discussed their favourite characters as well as the hard-right ideology they felt they could detect between the covers.

It is easy to see why Lord of the Rings might appeal to the far right. There are clear links in the text to the kind of Nordic mythology regularly mangled by white supremacists as well as the sense of an underdog fighting to preserve traditions of order and hierarchy against a malevolent foe.

Yet while Tolkien was certainly a man of the right he was no fascist. In a 1941 letter he described Hitler as a “ruddy little ignoramus” set on “ruining, perverting, misapplying, and making for ever accursed, that noble northern spirit, a supreme contribution to Europe, which I have ever loved and tried to present in its true light”.

Three years earlier a German publisher had sought Tolkien’s permission to issue a German translation, as part of which under Nazi law the author was required to provide assurance that he was acceptably Aryan.

“I am not of Aryan extraction: that is Indo-Iranian and as far as I am aware none of my ancestors spoke Hindustani, Persian, Gypsy or any related dialect,” Tolkien responded. “But if I am to understand that you are enquiring whether I am of Jewish origin, I can only reply that I regret that I appear to have no ancestors from that gifted people.”

While far-right organisations in other countries have embraced Lord of the Rings – a decade ago the BNP’s youth wing declared the film adaptations as essential viewing for “everyone who is in the slightest bit stirred by the feelings of our racial and national struggle to win back our homeland” – it is in Italy where that expression has been adopted most forcefully, with Meloni its highest-profile advocate.

When she attended the Hobbit Camps herself in the early 1990s, Meloni and her political associates would dress up as their favourite characters and cosplay in local schools. They took on nicknames drawn from Tolkien’s characters and, as she writes in her memoir, they would gather at the “sounding of the horn of Boromir” for cultural and political discussions.

Beyond Meloni, Italy’s highest profile Tolkien aficionado is the journalist and scholar of fantasy literature Giovanni de Turris, who wrote in his introduction to a 1991 translation of a biography of Tolkien that in the author’s work “you find exalted all the values that fascists and the traditional Italian right admire: spirituality, community, comradeship, order, adventure, heroism, a warrior spirit, the struggle against evil, a sense of duty and of mission, the heroism of the ordinary man; all those values, in fact, rejected by contemporary western society”.

In 2011 De Turris faced widespread criticism for having written prefaces to two works by Gianluca Casseri, a man with links to far-right organisations who ran a newsletter for Tolkien fans and who shot himself after murdering two Senegalese street traders in a racially motivated attack in Florence.

Yet while it is straightforward to see why Tolkien’s work might resonate with the far-right, the simplicity of the storytelling at its heart has seen him claimed by a range of ideologies. He was co-opted by the left in the 1960s for what they saw as warnings of the dangers of imperialism and the consequences of environmental destruction. When the Harry Potter novels became a phenomenon, American evangelicals held up Tolkien as an acceptable alternative to the paganism and witchcraft they perceived in JK Rowling’s work. Add in environmentalists, libertarians and pacifists and it’s clear how the Lord of the Rings cycle can be all things to all people.

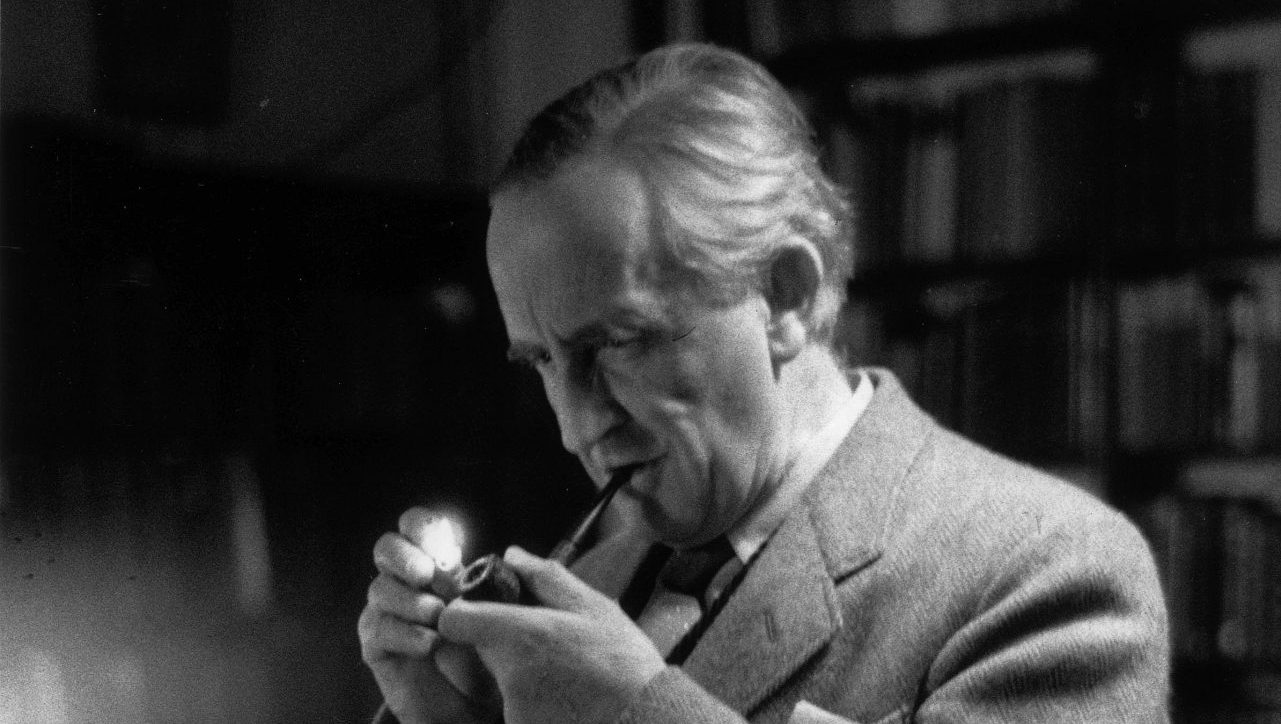

Thanks to Meloni, however, Tolkien is in danger of becoming embedded as an acceptable face of the far-right, something to which the tweedy, pipe-smoking academic would have taken great exception.

“I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations,” he said, “and always have done so since I grew old and wary enough to detect its presence.”

These are words to bear in mind when recalling the last Fratelli d’Italia rally on the eve of Meloni’s election victory last year, when the actor Pino Insegno, who provides the voice of Aragorn in the Italian-dubbed versions of the Lord of the Rings films, introduced the party leader with a bastardised version of Aragorn’s battle cry from The Return of the King, “Sons of Rohan, my brothers, people of Rome – the day of defeat may come, but it is not this day!”

Suddenly Rishi Sunak’s penchant for Jilly Cooper’s bonkbusters seems almost charming.