As political slogans go, it was not the catchiest: “Dare to make more progress”. This is Germany after all, a country that struggles to do theatrical politics, even on the rare occasions it wants to. The announcement of the “traffic light” coalition exactly a year ago was a moment of history. It was the first time that the three parties – the Social Democrats (SPD), Greens and the Free Democrats (FDP) – had joined together. It also brought an end to the remarkable 16-year era of Angela Merkel. So brightly did she shine that many Germans, even those who hadn’t voted for her, wondered how they would cope without her. All this was before Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

The war has changed everything. It has redefined every aspect of the new government’s programme. It has redefined Merkel’s legacy, and sent her reputation downwards.

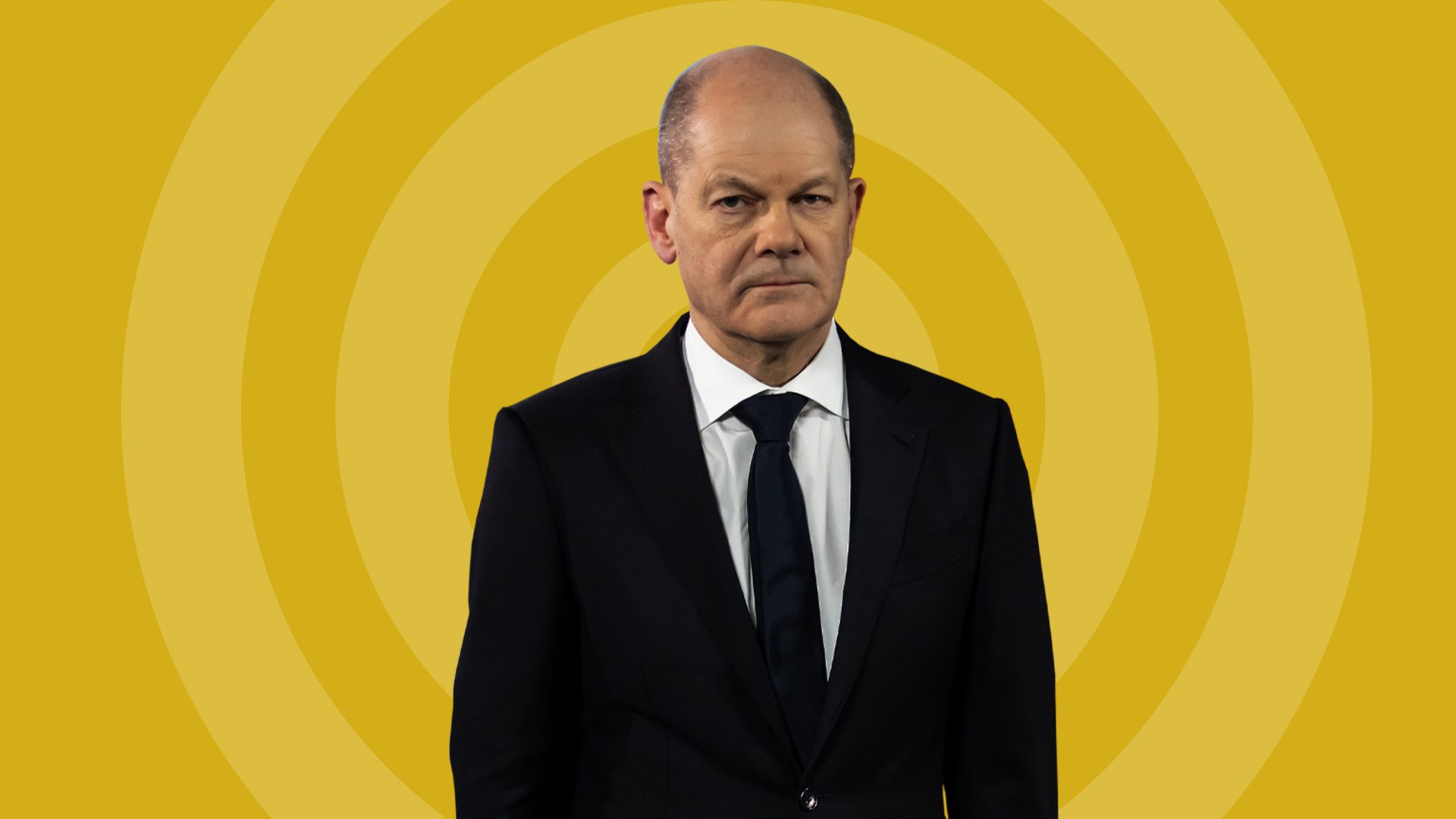

Olaf Scholz, her successor, has proven himself to be both supremely well-suited and ill-suited for the role of chancellor. He has kept the coalition on the road – no mean feat, given the fundamental differences between the parties. He has promised a generational change in the way Germany sees its role in the world. And he has so far navigated an economic and energy crisis.

Yet throughout this fraught period, Scholz has struggled to explain to the world and to his people what Germany is doing to help Ukraine and why it is worth the sacrifice. He does not do communication. He believes he will be judged on long-term results, not on day-to-day flourishes, or on the vagaries of public opinion. Is this doggedness the result of self-assuredness, or a gaping lack of empathy? The answer appears to be both.

Scroll back to September 2021 and the German elections. Social Democrats across the western world had been declared dead or on life support. Technocrats had been drowned out by bombast on the far right and far left. In November 2020, Joe Biden had scraped home against Donald Trump, but few people had much hope for him. Britain was a laughing stock, its politics dictated by Boris Johnson the clown. Only in a few countries, such as Spain, was the centre-left in power.

In Germany, there was huge focus on the Greens. Some polls suggested they were on the verge of becoming the largest party, but their prospective candidate for chancellor, Annalena Baerbock, stumbled. Merkel’s successor as leader of the Christian Democrats, Armin Laschet, imploded spectacularly. Then along came Scholz, who rose without trace, saying almost nothing of note on the campaign trail.

His diffidence turned out to be not just an election tactic, but a strategy for victory. Even as the coalition was announced, Scholz was eclipsed by the leaders of the two partner parties, Robert Habeck of the Greens and Christian Lindner of the FDP. He just kept his head down and, from the start of December, got on with the job.

The top priorities, according to the coalition agreement, were supposed to be digitisation, climate change and social reform. Foreign affairs hardly got a look in, though the Greens ensured some tougher-than-usual wording on Russia, China and human rights. But nobody was remotely prepared for what came next. I recall talking to a senior figure close to the chancellor a few days before the February 24 invasion of Ukraine. He scoffed at the idea that Putin would be so rash as to march into Ukraine. He was dismissive of US intelligence. The Americans had got it wrong on Iraq, my contact told me; once more they were getting a little excitable.

For decades, Germany sub-contracted its defence to the US, its energy to Russia and much of its trade to China. Suddenly, Scholz upended the basic tenets of foreign policy. On the evening of Saturday February 26 he summoned Lindner, now his finance minister, and told him he needed to find the small matter of €100bn (£86.7bn) for extra military spending. The next morning, an hour before he was due to address an emergency session of the Bundestag, Scholz summoned Habeck and Baerbock, informing them of his new plans.

The Zeitenwende speech was remarkable in the context of Germany’s postwar history. It was a reorganisation of the armed forces, a huge increase in defence spending to meet the Nato target of 2% of GDP, and an announcement that Germany would once more ship hard weaponry. Even more extraordinary was the psychological change that the speech demanded. Germans were being told that democracy had to be defended militarily, and Ukraine was the theatre in which the new world order was being fought.

For Scholz’s party this was a bitter pill to swallow. Ever since Willy Brandt’s “Ostpolitik” in the 1970s, the SPD had seen itself as the political wing of the peace movement and it had always favoured rapprochement with Russia.

This was one of the reasons why Scholz retreated into his shell. Germany did start shipping arms to Ukraine, but it did everything it could to avoid advertising it. This led to recriminations from Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, who in April abruptly refused permission for the German president, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, to visit Kyiv.

A sense of grievance took hold in Berlin. Why was Germany being singled out when others, such as the French, were doing less? To which the solution, I kept on saying to officials, was: get out there and tell the world how much you are actually doing. But that would show a more militaristic Germany, came the reply. Scholz and his team were caught in a Catch-22 of their own making.

There was another somewhat less innocent explanation. Scholz has adopted one of Merkel’s characteristics and taken it to a new extreme: he waits to see which way the wind blows, and then acts. Unlike Baerbock and Habeck, the two stars of the coalition, he does not bother to win people over or explain his case. As a somewhat unflattering recent profile in the weekly Die Zeit put it, the man who always knows best ends up saying that his brand new opinion has been his position all along.

The recent controversy over ownership of the Port of Hamburg, the EU’s largest for container ships, illustrates how Scholz operates. In spite of open criticism from several government ministries, and for all the talk of “on-shoring” of vital supply chains, he went ahead with a decision to give a Chinese shipping company, Cosco, a 25% minority stake in the port. He did not bother to explain himself beyond saying that he had reduced it from the original bid of 35%.

He has an air of complete unflappability no matter what is thrown at him. Bubbling along throughout the year has been a historical scandal over a multimillion-euro tax fraud scheme while he was mayor of Hamburg. Questioned by a state parliamentary committee in the northern city for a second time, he denied influencing the private bank, MM Warburg & Co, which is alleged to have swindled the German state out of an estimated €300m between 2007 and 2011.

When viewed from the perspective of a Brexit island whose summer and autumn consisted of three prime ministers and a drowning economy, Scholz’s doggedness has its merits. Germany has diversified its energy sources with commendable speed and efficiency. From a position of dangerous dependency, with 55% of the country’s gas coming from Russia, it brought in terminals to store liquefied natural gas from the US, Norway and the Gulf and is now back to full capacity. It can no longer be blackmailed by Russia.

Scholz is earning grudging admirers, if not friends. The Americans have cut him considerable slack on Ukraine. The UK is trying to befriend him. Keir Starmer sees him as a role model. Paradoxically, the worst relations are with Germany’s traditional best friend – France. A joint meeting of both cabinets was cancelled last month after a sharp chilling of relations with Emmanuel Macron. The French president was aggrieved at Scholz’s solo meeting with President Xi Jinping in Beijing, a week after the Communist Party Congress. It did not go unnoticed in Paris and elsewhere that the German delegation contained CEOs of a dozen leading businesses.

Yet Scholz emerged from 10 difficult hours in the Chinese capital with an important declaration, jointly opposing “the use or threat of use of nuclear weapons”. This was far more than symbolic. Although Russia was not named, this was a warning from Xi to Putin, impressively brokered by the chancellor, for all to see.

The phrase “langsam aber sicher” (slow but steady), used to define Merkel. Her legacy plummeted from unrealistically high to unfairly low within weeks of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. It will settle, correctly, somewhere in between. Scholz has adopted her circumspection, but he has injected a new steel into German foreign policy. It is not quite the case of Germany First, but he is making it clear: he will do things his own way.