My mother loved England. But just like thousands of others who share that love, there was a catch. It was something that precluded her from being what some would call ‘one of us’.

She was Italian, by birth, culture and inclination and worse, she’d married an Englishman who loved Italy more than his native land.

But love England she did – for all the obstacles it put in her place when she arrived in the early 1960s – just not the England trumpeted by the bad boys of Brexit and their ilk.

Her’s was a migrant’s tale and her only disappointment came when England, her England, fell short of her idealised image of the country.

It was an image which she had first conjured up reading about this sceptred isle as a schoolgirl and later when she started her married life here.

Pina, her family nickname, loved the England of rolling landscapes, walled gardens and village greens – elements loved by many, from the most conservative little Englander to visiting tourists.

But hers was also the England that gave refuge to the exiled Italian patriot Giuseppe Mazzini and generations of political exiles, that gave birth to Thomas Hardy and the National Trust and where – decades after their parents and grandparents had struggled to pave the way – black and Asian schoolgirls could finally walk carefree past her house, arm in arm with white friends, confident and at ease in their own identities.

The only thing about England to which she couldn’t reconcile herself was that you could never guarantee your washing would dry if you hung it outside.

My mother was born Giuseppina Nicosia in 1942, in the historic Roman neighbourhood of Testaccio – where centuries earlier the ancient Romans dumped their rubbish – in an Italy still under fascist rule and soon under Nazi occupation.

Indeed a year or so after Pina’s birth her eldest brother was sent to live with shepherds in the mountains, for fear the Germans would round him up, alongside other able-bodied men, for a bloody last-ditch defence of Rome against the Allies, coming up from the south.

Life after the war and before the economic boom of the 1950s was far from sweet. Severe economic hardship – Italy was then still extremely poor – was coupled with an overbearing cultural and religious conservatism. Yes, the priests really did censor any Hollywood screen kisses.

In the early Sixties – as Italy began to attract artists, filmmakers and writers drawn to the bohemian awakenings of La Dolce Vita – a search for something else led Pina to enrol for English classes at the British Institute.

Here she met and captured the heart of ‘un Inglesotto’, a young Oxford graduate teaching in a city he had already fallen head over heels for.

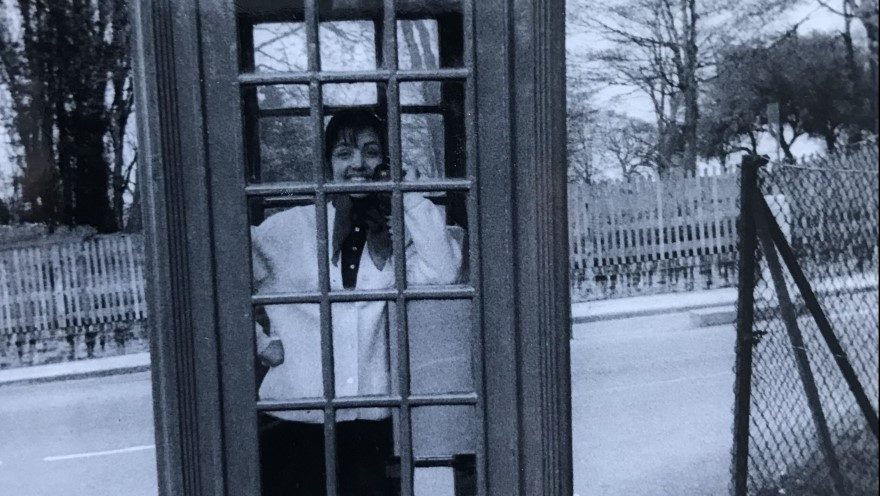

They married in his home town of Sheffield and she gave birth to me in a gloomy grey London in December 1964, taking me by pram around Dulwich Park, catching the bus to Soho to buy then prized olive oil and spaghetti from the Italian delis, selling jam from her doorstep to supplement her young husband David’s freelance income, until they moved with me back to Rome

in 1967.

There – as the clash of generations and the unfinished resistance against fascism set Italy on its path to l’autunno caldo – the hot autumn of 1969-70 – they threw themselves into the political upheavals of the day.

At one stage they joined a campaign for better children’s facilities by taking part in the occupation of a derelict lot and turning it into a playground. My mother was no doubt emboldened by her experience of the more progressive provision of play facilities she had experienced as a young mother in the UK. If her son could enjoy them in London, why not others in Rome? As a result my earliest political memory is standing guard at the entrance to the plot, under instructions from a family friend and compagna [comrade] to raise the alarm if I spotted the police arriving.

After we moved back to England, in the early Seventies, Britain’s relatively honest political culture and sense of civic duty stood for Pina in contrast to an Italian political life where the values of the Republic were daily undermined by choking corruption and clientelismo [who you knew in positions of influence] and the prevalent menefreghismo [I don’t give a damn] of many.

An admirer of the British passion for conservation and environmental protection, she despaired at the worsening urban pollution and still untrammelled coastal development that greeted her whenever she returned to Italy.

But while she initially viewed England through rose-tinted glasses, there were invariably moments when her adopted country let her down.

The Nationality Act of 1981 didn’t help, forcing her to abandon Italian citizenship in favour of a British passport for fear of a knock on the door by Her Majesty’s immigration officers.

Thirty-five years later came another low point, with the Brexit referendum representing a personal insult and rejection by her fellow countrymen.

That sense of never quite being at home, never fully welcome, was shared by thousands of others in her shoes.

It made itself felt early on, in an incident that reflected the shared experience of those migrants. During the winter of ‘65 Pina, then 23, pushed my pram around Dulwich and Peckham looking for a new flat. My father’s journal recounts how at one house a black woman answered the door, only to tell her the flat was already taken.

But as my mum turned to go the woman called her back. “Just a minute, you’re not English are you?” she asked.

“No, Italian,” said Pina.

“Oh well, as long as you aren’t English,” the woman responded, inviting her inside. “It’s an attic, one room, shared kitchen and bath. £7.”

No, my mum, who died last year, wasn’t English, but she still loved it here.