Fifty-five seconds. Not even a minute, yet enough to define a life and cleave it irrevocably into before and after.

When Niki Lauda lined up his Ferrari at the start of the German Grand Prix on August 1 1976 he had every right to feel on top of the world.

The reigning champion’s season had got off to a blistering start with four wins in the first six races and second place in the other two. A fortnight earlier he’d won the British Grand Prix, making it five wins in nine and putting him well ahead of his nearest rival, James Hunt, in the championship.

The previous year, Lauda had become the only driver ever to complete Nürburgring’s 14-mile lap in under seven minutes but he had little affection for the winding German course. Built in the 1920s, its twisting circuit was no longer suitable for modern Formula One cars and had led Lauda to call unsuccessfully for a boycott of the race on safety grounds at a meeting of the Grand Prix Drivers’ Association a few days earlier.

Showers on the day of the race had most drivers setting off from the grid in wet weather tyres, but it was soon clear the course was drier than anticipated. Lauda pulled in during the first lap to replace his with dry ones and was fighting his way back up the field when on the second lap his rear suspension failed as he took a tight left turn, sending him smashing into the barrier on the right of the track. The collision ripped the right-hand side of his vehicle clean off and tore off his helmet.

With the race not even two laps old, Lauda’s fuel tanks were almost full and, as the vehicle rolled backwards into the middle of the track, they burst into flames, engulfing the cockpit. Brett Lunger’s Surtees had just come around the bend and while he braked as hard as he could he still bumped the wrecked Ferrari head-on, pushing the burning car towards the edge of the track and using up vital seconds.

Three drivers battled the flames and dense black smoke to release Lauda’s seatbelt and haul him out of the cockpit. Without their quick action, the 27-year-old would have burned to death.

He spent 55 seconds at the heart of that raging fire. Suffering severe burns particularly to his head and hands, not to mention a broken collarbone, Lauda was airlifted to hospital where his condition deteriorated to the point where, three days after the crash, a priest was called to administer last rites. “I kept telling myself, if he wants to do that it’s OK,” Lauda recalled. “But I’m not quitting.”

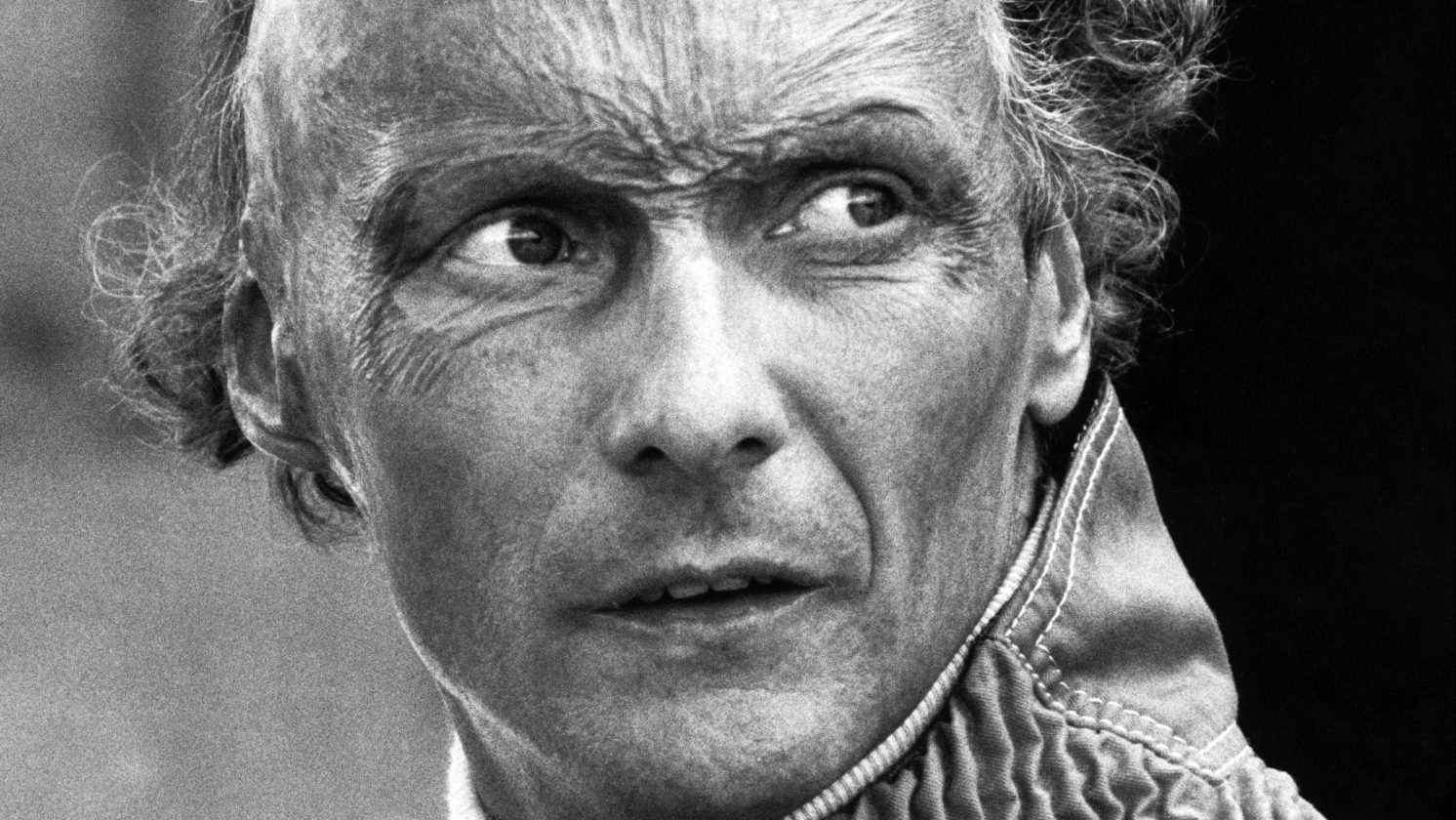

Lauda’s injuries were horrific, including the loss of his eyelids, the almost total loss of his right ear and burns to his scalp so severe he was never seen in public again without a hat. Later, he would remember: “I asked a nurse in the burns clinic, ‘when can I look in the mirror?’ ‘Any time,’ she said. It should never have been allowed. She switched on a neon light, and because of the heat and the water retention my head went straight into my shoulders… ‘Shit’, I thought. Of course, it got better and better. I had seen my injuries at their worst.”

Lauda was determined not just to return to racing but to retain his world title. Barely three weeks after the accident he showed up at the Ferrari test track at Fiorano, near Bologna, to prove to team management and Enzo Ferrari himself that he was ready to return to the cockpit.

The fact Ferrari had brought in a replacement driver within a day of the accident had irked Lauda. He was the reigning world champion. They had no business writing him off like that.

“He was a vision that I can never forget in my life,” recalled the Ferrari team manager Daniele Audetto. “Niki arrived in Fiorano in his plane that he apparently flew to Bologna himself. He was so pale, the scars, he’d lost his hair, he could not close his eyes. He was like a ghost.”

Lauda, his racing overalls hanging loosely from a frame now a stone and a half lighter than when he’d started the race at the Nürburgring, climbed into the cockpit, drove out of the pit lane with pain searing through him and proved to Ferrari he was worthy of a place on the grid at the forthcoming Italian Grand Prix. There was a world championship to retain and he had already missed two races. He was not missing another one.

Thirty-three days after the Nürburgring inferno, his burns sore and weeping beneath his bandages, Lauda took fourth place at Monza.

Going into the final grand prix of the season in Tokyo, Lauda was still three points ahead of Hunt but heavy rain combined with vision problems – his tear ducts had been badly damaged in the fire – convinced Lauda that it was too dangerous to continue. He retired from the race, leaving the way open for Hunt to win the championship.

The following year he was world champion again, cementing his reputation as one of the greatest and bravest drivers of all time. The singular determination that put him back into the car at Fiorano and then on the start line at Monza had been there from the beginning. Those 55 seconds had only enhanced it.

Born into a Viennese family that made its fortune in the papermaking industry, Andreas Nikolaus Lauda was expected to enter the business founded by his grandfather. Instead, young Niki became obsessed with cars, racing Mini Coopers in Alpine climbs as a teenager before progressing to Porsches and ultimately incurring the wrath of the Lauda dynasty.

Aghast at his ambition to become a racing driver, the family refused to finance his fledgling career, forcing Lauda to incur significant debts – including the £20,000 it cost him in 1971 to buy a place on the March grand prix team. When his grandfather intervened with the bank to cancel a loan agreed for this amount, Lauda severed all contact with his family. “I secured the loan against my life insurance. I put their logo on my helmet, which is how I got out of the mess my grandfather put me in,” he said later. “I broke with him, and the poor guy died before we had a chance to make peace.”

Two years later he moved on to the British BRM team but was still paying to drive until a placing in the 1973 Belgian Grand Prix elevated him to the payroll. Ferrari signed him in 1974, prompting an impressive fourth-place finish in the championship and within a year he had won his first world championship.

He retired from the track in 1985, a year after winning his third world title by half a point from McLaren teammate Alain Prost, to concentrate on the airline he’d launched in 1979, but the legacy of that 55 seconds in the flames at the Nürburgring never left him. It was there every time he looked in the mirror, it was there in the lung transplant he was forced to endure a few months before his death, the result of toxic fumes inhaled while strapped into the cockpit 40 years earlier.

“Formula One is about controlling these cars and testing your limits,” he said in 2015. “This is why people race – to feel the speed, the car and the control. If in my time you pushed too far you would have killed yourself. You had to balance on that thin line to stay alive.”

If anyone knew just how thin that line was it was Niki Lauda who, for 55 seconds one afternoon in 1976, walked it like nobody before.