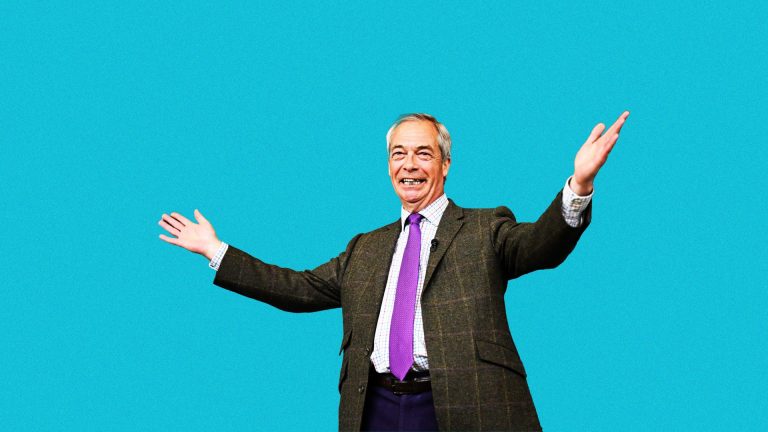

When considering Nigel Farage’s latest intervention into British politics – his campaign for a ‘referendum on net zero’ – it’s worth a read of Michael Crick’s recent, excellent biography of the former Ukip leader, One Party After Another, specifically where he wins back the party leadership in 2010.

One of his opponents is David Campbell Bannerman, an MEP, whose “main gripe” with Farage, Crick writes, “was that he seemed almost completely uninterested in policy”. He quotes Campbell Bannerman as saying “to me, a political party is policies… Nigel was never interested in policy; he was always unhappy with it”. And in his speech to the party conference that year, he told his audience he didn’t want a party of “those who think their role is to compete with Dan Hannan for YouTube hits”.

A fat lot of good it did Campbell Bannerman – he came third with 1,404 votes, or 14%, as Farage took the leadership. He then returned to the Tories and now enthusiastically retweets Hannan’s views about Brexit’s success.

But it’s still worth bearing in mind now Farage seeks to relaunch himself as a campaigner on environmental policy. Because one of the striking takeaways from Crick’s whopper of a book (550 pages before footnotes on a man who has never been an MP or held ministerial office) is that Farage doesn’t appear to believe anything – anything – beyond the fact that Nigel Farage should get a lot of attention (he also appears to like drink and sex a lot, although that is an entirely different article).

The Brexit Party was a one-issue party. The only period in which Ukip’s non-EU policies attracted any sort of media attention was during the 2010 general election when (a) Farage wasn’t leader, and (b) they were utterly mad, their manifesto promising to introduce a dress code for taxi drivers, repaint trains in traditional colours, make London Underground’s Circle line circular again and investigate discrimination against white people at the BBC.

But even on the one policy he ever showed any interest, and devoted his political life to – that the UK should leave the European Union – it’s never clear, even after reading Crick’s book why he thought that. There’s some vague thoughts around democracy (even if, in both the parties he leads, he doesn’t have much time for that internally) and plenty of Johnny Foreigner bashing (although one schoolfriend tells Crick Farage’s obsession was the first, not second world war).

But there’s no vision for what that exit from the EU institutions would allow that Britain to be, no speech, no manifesto, as to how its economy would be structured, where the country would move geopolitically. Even the likes of the aforementioned Hannan tried to put some intellectual ballast behind their campaigns even if their talk of ‘Singapore on Thames’ turned out to be as deluded as many of us thought.

But Farage: nothing. Nothing beyond a thirst for attention, for the media limelight. Time and again in Crick’s book, Farage’s political energies are devoted to taking down those internal figures who threaten his omnipotence. Most famously, in 2004, Robert Kilroy-Silk is lured into the Ukip fold. The Piers Morgan of his day, having presented his own daytime TV show for 17 years, he gained the party attention like never before. It was never likely to last. Tensions with Farage quickly emerged; he was out within the year. “Nigel wasn’t known, and I was this celebrity,” Kilroy-Silk later said.

All this needs to be beared in mind when considering Farage’s latest referendum call. Look at where he is now compared with his fellow Brexiteers. Boris Johnson is prime minister, Michael Gove effectively running domestic policy across Whitehall. Crick may attribute Brexit to Farage’s long, often lonely campaign, but – some excitable calls from fringier Tory MPs once upon a time for him to be elevated to the peerage and made foreign secretary aside – he is presenting a rentaquote TV programme on GB News, a channel whose noise does not reflect its influence.

In the criminally underrated TV comedy Psychoville, a character called Oscar Lomax is an avid collector of stuffed toy animals who needs just one, a crocodile named Snappy, to complete his prized collection. When – spoiler alert – at the end of the series he finally lays his hands on it, he walks to a nearby cliff and throws it off. He never wanted it – just the thrill of the chase.

One could be reminded of that character when watching Farage launch his campaign for a referendum on net zero. It’s questionable whether he cares much about the subject either way – his long record as a Member of the European Parliament doesn’t throw up many mentions. But he does care about being famous, being relevant – and any salience he once had, ironically, went once Britain departed the EU.

One of Farage’s teacher’s, Neil Fairlamb, tells Crick that on the day of his pupil’s departure from Dulwich College in 1982, he told him: “Nigel, I have a feeling you will go far in life, but whether in fame or infamy, I don’t really know.” He recalls that Farage looked back at him and replied: “Sir, as long as it’s far, I don’t care which.”

Farage hasn’t grown up much in the intervening 40 years. His new campaign, though, may well be his final, desperate bid for relevance.