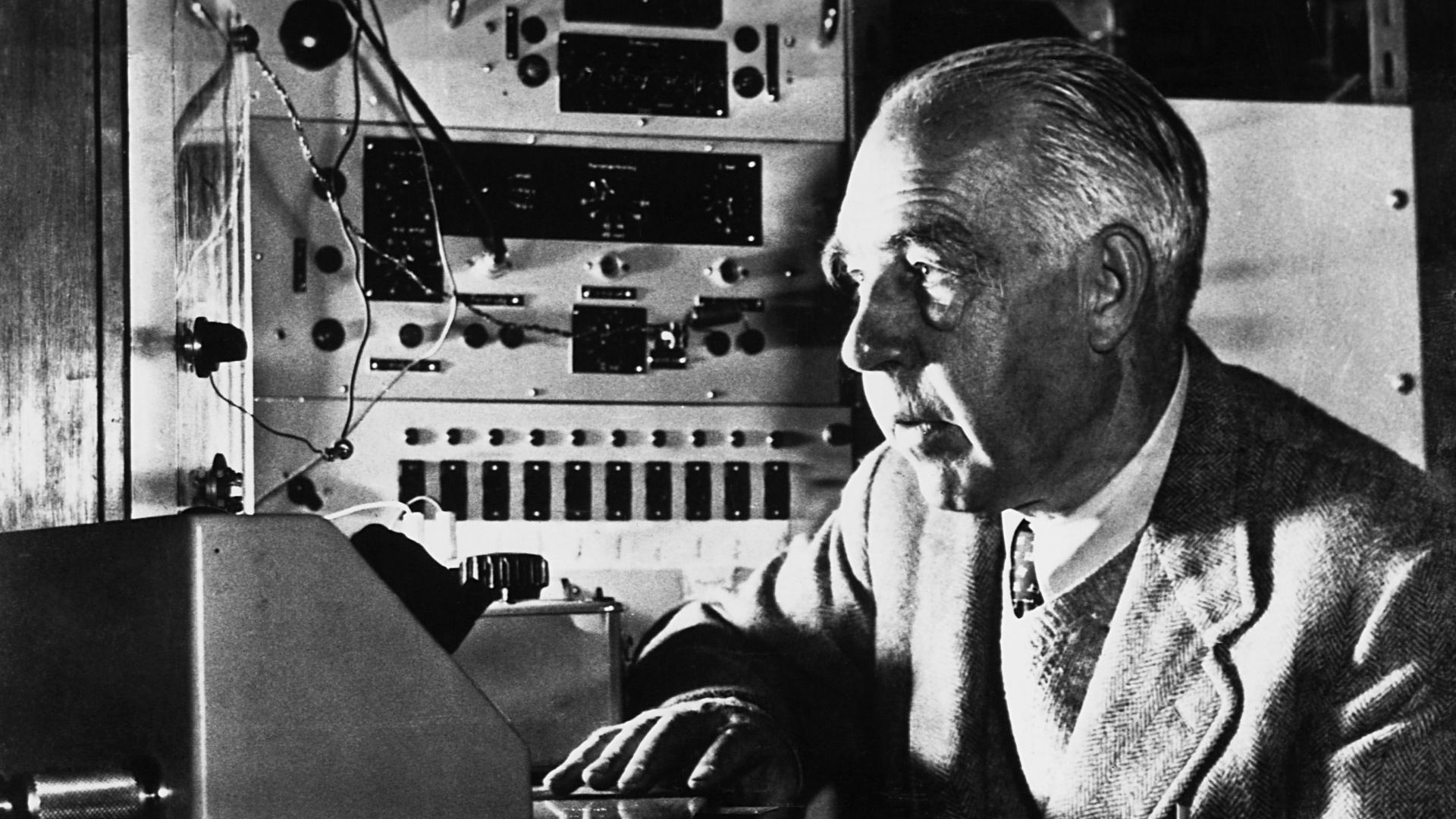

In a 20th century that saw unprecedented scientific advances, two physicists stood head and shoulders above the rest. One enhanced our understanding of the universe, moved to the US, became a household name, embraced modern media and embedded himself in the popular culture of the era. The other revolutionised human knowledge of the atom, stayed mostly squirrelled away in Copenhagen and remained only a vaguely familiar name to those outside the world of scientific research.

Nobody stuck a poster of Niels Bohr, wild-haired and with his tongue out, on

their wall, but the Dane did as much for expanding the range of scientific knowledge in the modern age as Albert Einstein.

Awarded the 1922 Nobel prize for Physics in recognition of his work on the structure of the atom, Bohr advanced the findings of Ernest Rutherford, under whom he had studied in Manchester, to confirm the atom as a nucleus of protons and neutrons surrounded by orbiting electrons which respond to a change in energy levels inside the shell of the atom with quantum jumps. It was a discovery that changed the world, not least in paving the way to the creation of the atomic bomb.

Nuclear fission’s military use caused Bohr great ethical distress despite his

consultancy on US research and development during the second world war and especially after a much-mythologised 1941 meeting in Copenhagen with his former assistant, Werner Heisenberg – head of Germany’s nuclear programme.

After the war he campaigned ceaselessly for the great powers to share their atomic secrets, a position many regarded as naive – in 1957 the New York Times described Bohr as “a moon-faced, bemused grandfather” – but one forged from his unshakable faith in the principle of truth and the dangerous fallibility of scientific certainty.

“He utters his opinions like one erpetually groping and never like one who believes himself to be in possession of the definite truth,” Einstein said of

Bohr’s lifelong opposition to dogmatism.

“Every sentence I utter must be understood not as an affirmation but as a question,” Bohr would tell students.

He was revered even among the world’s finest minds for his extraordinary

intelligence and speed of thought. After a year working under him in the mid-1930s, fellow Nobel-winner James Franck took up a professorship in the

United States because Bohr’s brilliance was so overwhelming.

“He never allowed me to think anything through to the end,” said Franck. “I made some experiments and when I told Bohr about them he told me immediately what might be right and wrong about them. It was so quick that

after a time I felt unable to think at all because Bohr’s genius was so superior.”

This exceptional scientific intellect was evident from an early age. Bohr’s father, Christian, was a professor of physiology twice nominated for the Nobel prize so it was no surprise that Niels felt a similar pull towards the

laboratory. He showed immense early promise, winning a gold medal at the

age of 19 in a competition organised by the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences for work on the surface tension of water, a competition Bohr only decided to enter at the last minute.

Somehow he found time between his studies to play in goal for the leading Danish football club Akademisk Boldklub, where his mathematician brother played at outside left.

Goalkeeper is a position long associated with deep thinkers, from Albert Camus to Che Guevara. For Bohr, in a key game against a German team, the thinking outdid the goalkeeping when a speculative punt from midfield

bounced into his net while he stared at the ground oblivious, pondering a

mathematical problem he’d devised to help pass a lull in play.

He was chair of theoretical physics at the University of Copenhagen by the time he turned 30 and in 1921 founded the Danish Institute of Theoretical

Physics, a global centre for research into quantum physics, and it drew in

scientists from across Europe. At first Bohr lived and worked at the institute,

but after his Nobel win the following year, Carlsberg awarded him a house in

recognition of his achievement. It came with a beer tap pumped directly from the brewery.

For most of the 1930s, Bohr had taken in Jewish academics fleeing Germany and employed them at the institute before arranging jobs and travel for them in safer locations. When Germany invaded Denmark in the spring of 1940, however, every foreign physicist left the country. Bohr managed to continue his work largely without interference but the following year brought Heisenberg to the institute. Their private meeting remains the subject of speculation to this day.

Heisenberg maintained he was relating the opinions of Germany’s leading

scientists that an atomic bomb was possible and sounding out Bohr on the

morality of the weapon. He would later claim he and his colleagues were quietly sabotaging German progress all along.

Bohr contended that he’d been shocked by his old friend’s conviction that Germany was certain to win the war even without the nuclear weapons they

were well on the way to developing, and ended the meeting immediately.

In 1943 he realised that his maternal Jewish background made him a target for a Nazi regime ramping up their assault on Europe’s Jews and escaped with his family to Sweden. From there the British flew him across the North

Sea in the bomb compartment of a Mosquito where some football-style absent-mindedness almost proved fatal when he forgot to put on his oxygen

mask for the high-altitude flight and spent its duration unconscious.

From Britain he travelled to the US, meeting Einstein at Princeton and visiting the secret nuclear testing site at Los Alamos in New Mexico. While he never worked directly on nuclear weapons, nor even saw one being tested, he took on an advisory role, realising that with the genie out of the bottle and nuclear weapons about to become a reality it was infinitely preferable that the Allies should develop them first.

Despite this, and foreseeing the postwar arms race, Bohr remained convinced that cooperation between the great powers over nuclear technology was the only way to achieve long-term global stability. The Manhattan Project, he believed, should be shared with the Russians. This led to a stormy 1944 meeting with Winston Churchill during which the British prime minister described Bohr as “this blithering idiot,” growing so concerned that he warned the Americans, without foundation, that the Dane might reveal nuclear secrets to the Soviet Union.

As soon as the war ended, Bohr returned to Denmark and watched the cold war confirm his fears of a nuclear arms race. He continued advocating for

openness for the rest of his life, convinced the only truth that mattered was scientific truth, the kind that allowed questions and debate, the kind best shared, the kind for which there was no place in the black-and-white world of international politics.

“There are trivial truths and there are great truths,” he said. “The opposite of a trivial truth is plainly false, but the opposite of a great truth is also true.”