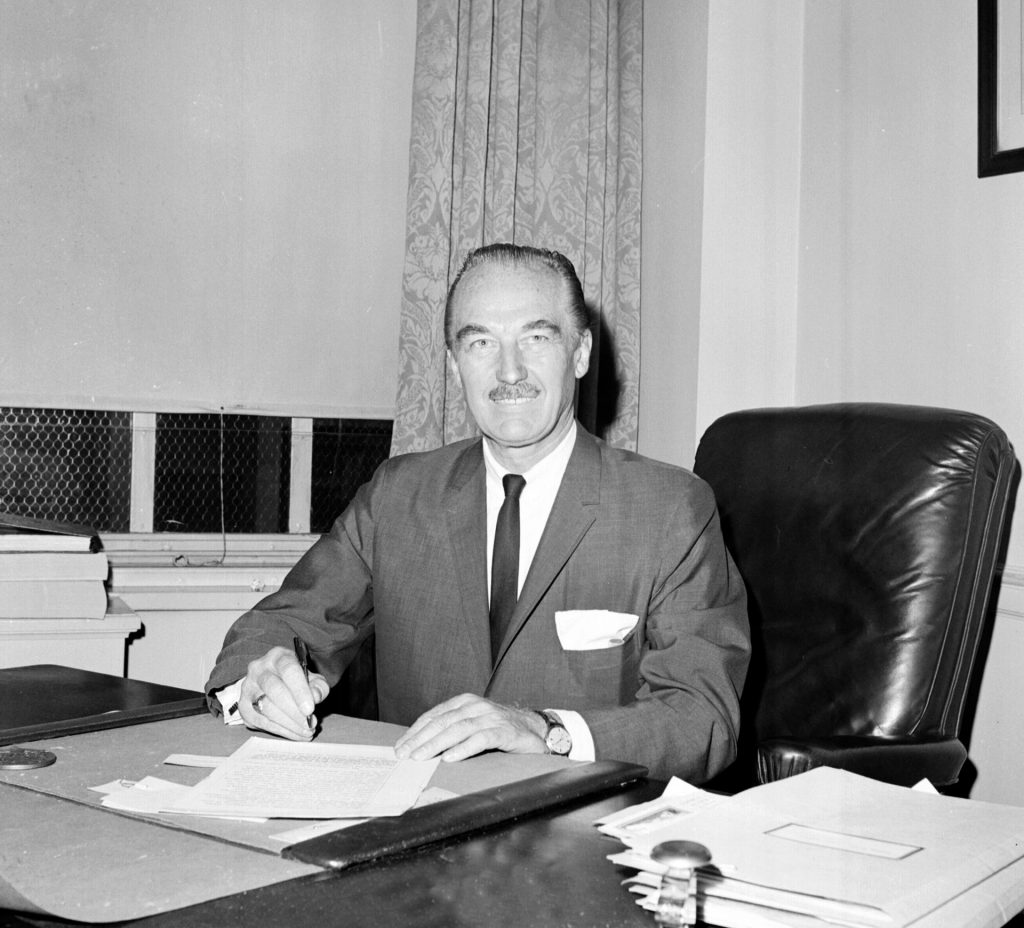

The private office of Fred Trump Senior, at the headquarters of the family company in Brooklyn, was a square room. Low lighting illuminated walls covered with plaques and framed certificates, and wooden busts of Native American chiefs were scattered about.

On his desk were thick pads of cheap notepaper and an endless supply of blue Flair markers, which his granddaughter Mary would play with as a child, spinning around in his desk chair. Fred Sr was at this desk every day, as he had been for 50 years, dressed in his three-piece suit and with his trademark moustache neatly brushed.

And by 1992, it was a lie, concocted by his children to trick him into thinking he was still in control of his property empire. A Potemkin office.

At this desk, he was a tragic figure. For his final nine years, as the end of his life neared and his Alzheimer’s disease increased in severity, Fred Sr was still coming in every day. He believed in the cruciality of hard work. He thought he was still in control.

But the paperwork he was shuffling was all blank. No one read the forms he was signing. His phone was disconnected from the outside world, just going through to one secretary who sat in the lobby outside and who was in on his children’s plan to isolate and control their father.

Fred Trump Sr was born in 1905 in New York, the first-generation son of German immigrant parents. “I always wanted to be a builder,” he told the New York Times in 1973. “It was my dream as a boy, just as some kids want to be firemen or cops or chemists.” His father died when he was 11 during the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic and, as a teenager, Fred Sr took odd jobs to help with the family finances.

In a style that would later come to be a trademark of the Trump dynasty, many of the details of Fred Sr’s life are murky, quasi-mythic by design. He told the Times: “When I was 16, I built a garage for a neighbor, probably not the greatest garage ever put up, but the experience reinforced my hope of doing something creative with wood and bricks and cement.”

After graduating from high school in 1923, he got a job helping with horses dragging lumber for building sites, before becoming a carpenter’s assistant, and took night courses in various elements of construction. He claims to have built his first one-family house in 1924.

According to his biographer, Gwenda Blair, a key part of Fred Trump’s early success in real estate came in 1934, when he acquired a mortgage-servicing company as part of a fire-sale of assets of a bankrupt firm called the J. Lehrenkrauss Corporation. This allowed him to identify properties nearing foreclosure and swoop in to buy them cheaply before anyone else.

During the war, Fred Sr was contracted to build temporary accommodation for thousands of workers at New York’s navy yards. He broke ground on his first large-scale development, Shore Haven Apartments in Brooklyn, in 1949, and from there went on to build a vast real-estate empire. Its true value has always been intentionally obscured, but it is estimated that by the time he became the inhabitant of his phoney Brooklyn office where nothing was real, the company may have been worth almost a billion dollars. He died in 1999.

He had four children. The oldest, his only daughter, Maryanne, would later become a federal judge. Then three boys: the oldest was named Fred II; the youngest, Robert. But it was the middle son, Donald, the future president, who was his favourite. Even at the height of his later dementia, multiple sources – hostile and friendly – agree Donald’s was the only face Fred Sr could still reliably recognise.

It didn’t help that Fred Trump II – known as Freddy – permanently earned his father’s enmity by trying to escape from the family business. Real estate made Freddy miserable: his dream was always to fly. But when he announced in December 1963 that he was quitting to pursue a career in aviation, it enraged Fred Sr.

Freddy’s story is a tragic one. His career as a professional pilot for Trans World Airlines was brought to an end after just a year by the quickly developing alcoholism that would later kill him, in 1981, aged just 42. While Freddy returned to work for his father again, their relationship never recovered, and Freddy spiralled into terminal depression.

After Fred Sr’s death in 1999, when the patriarch’s will was finally unveiled, Freddy’s children had been written entirely out of any inheritance. This set off a huge intra-family lawsuit, with Freddy’s two children – Fred III and Mary – claiming Donald had wielded “undue influence and coercion” to cut them out while their grandfather was in a diminished mental state because of Alzheimer’s.

Alzheimer’s is a degenerative brain disease. It is characterised by a buildup of plaque on neurons in the cerebral cortex, but its causes and mechanisms are not yet fully understood, and risk factors can be both environmental and genetic. It is the most common cause of dementia – the decline and eventual destruction of memory and cognitive ability.

Fred Sr’s mental state first started to decline in the 1980s. One time, a family friend recalled to Vanity Fair, he came downstairs wearing three ties. Another time, he reportedly pointed at the Empire State Building and said “that’s a tall building, isn’t it? How many apartments are in that building?”

He started misplacing things, forgetting conversations and faces. Often, if his limousine stopped at traffic lights he would “just get out of the car and start walking away,” his grandson, Fred III, told People magazine in 2024.

James Merikangas is clinical professor of psychiatry and behavioural health at George Washington University, where he specialises in the neurology of cognitive decline and regularly gives expert testimony in court cases where degenerative brain conditions have led to a contested will.

He tells me the rule in situations like this is “ do they know what they’re doing, what their estate is, do they know who they want to give it to, and is it done freely. But that’s obviously quite vague,” he adds.

One problem is that the definition of “competence” in the context of a degenerative brain condition is poorly defined in law. “ Some people with Alzheimer’s can make a will and be competent because their only problem is maybe with their recent memory as opposed to judgment and remote memory,” he tells me. “Now, those people can tell you what happened 20 years ago, but can’t tell you what happened yesterday. So, you know, it’s not easy.”

“ There are cases where there’s a large estate and lawyers on each side, and they fight and they fight and they fight until at the end of the thing there’s no money left because the lawyers have got it all,” he says.

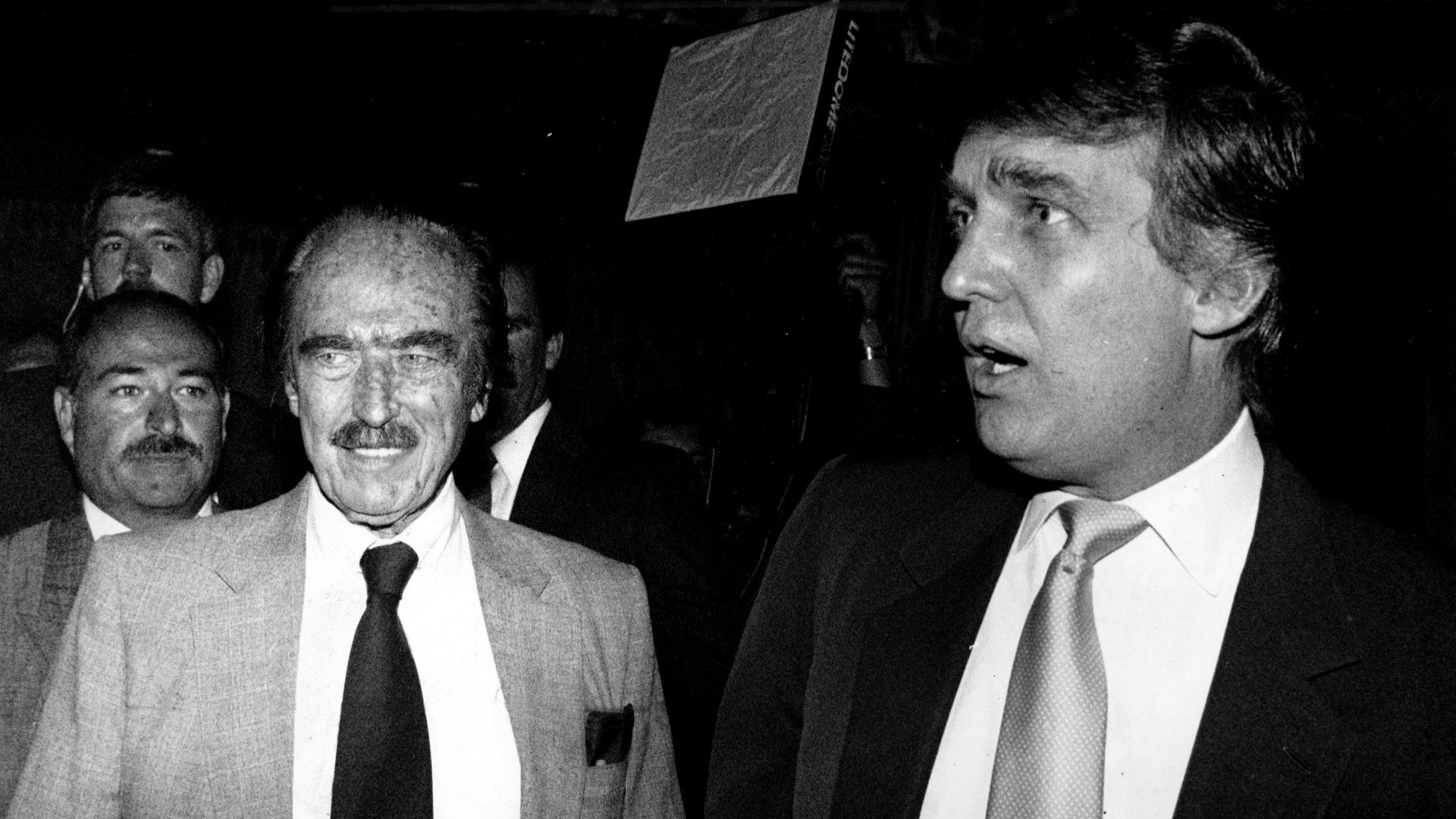

From the 1970s onwards, Donald steadily increased his position of power within his father’s business.

He was made president of the company in 1971, under his father’s chairmanship, and rebranded it soon after as “The Trump Organization”.

Fred Sr fed millions of dollars to Donald to help his business projects, many of which abjectly failed. A 2018 New York Times investigation found that by 1990 Fred had backed or bailed Donald out to the tune of at least $46.2m, and potentially considerably more than that, in the form of near-unlimited personal credit and other movements of capital.

By the beginning of the 1990s, many of Donald’s ventures – especially his airline, Trump Shuttle, and his extraordinarily ill-conceived casinos in Atlantic City – were collapsing. “Already susceptible to believing the best of his worst son,” Mary Trump – Fred’s granddaughter – writes in her memoir, Too Much and Never Enough: How My Family Created The World’s Most Dangerous Man, the increasing toll of Fred Sr’s dementia made it “easier over time for him to confuse the hype about Donald with reality.”

Donald, meanwhile, “was confronted for the first time with the limits of his ability to talk or threaten his way out of a problem,” Mary writes. So the future president “seems to have come up with a plan to betray my father [Fred Jr] and steal vast sums of money from his siblings.”

Mary says her Uncle Donald secretly approached two of his father’s longest-serving employees: family lawyer Irwin Durbin and accountant Jack Mitnick, and enlisted them to draft a codicil to Fred Sr’s will that would put him in complete control of the estate after his father died.

According to Mary, the idea had been to present the document “as if it had been Fred’s idea all along.” But “my grandfather, who was having one of his more lucid days, sensed that something was wrong” and contacted his daughter, Maryanne. She showed it to her husband, John Barry, a lawyer.

“He says, ‘holy shit’. It was basically taking the whole estate and giving it to Donald,” Maryanne told Mary, her niece, in one of a number of conversations between the two that Mary secretly recorded, and later released.

“My grandfather’s decline wasn’t smooth and steady,” Fred III wrote in his own autobiography in 2024, All In The Family. “Advancing dementia rarely is. He’d seem OK some days. Then he’d be really out of it. He’d remember some things and not other things. It was often hard to predict which.”

Fred III describes his grandfather becoming more “agitated” as his condition continued to decline in the early 1990s. “He would scream, and I witnessed this, scream at my grandmother for spending too much money,” he wrote; behaviour which “kept escalating and escalating, to the point where doctors would say to my grandmother, ‘You really shouldn’t be staying in the same bedroom with him at night’.”

The woman Fred III and Mary Trump refer to fondly as “Gam” was Mary Anne MacLeod, a Scottish-born socialite who moved to America in 1930. In 1991, she was attacked and mugged near her Long Island home. Fred III recalls hearing about the attack on the radio. “No one in the family bothered to call and tell me about what had happened to Gam,” he wrote. “I had to hear about it from a friend who heard the story on WINS radio. I drove immediately to Booth Memorial. When I walked into the emergency room, Rob [Donald’s brother] looked shocked to see me, like, ‘What are you doing here? How did you find out?’” The children were closing ranks around both their grandparents.

After the attack, which caused a brain haemorrhage, Mary Anne’s withdrawal from public and family life seemed to increase the speed of her husband’s decline. In 1992, Fred Sr was analysed by a specialist, Rajendra Jutagir. In a report the New York Times revealed in 2020, Jutagir wrote that Fred’s immediate ability to recall was “poor”, ranking below the 15th percentile for his age group. After a 30-minute delay, Jutagir wrote, Fred Sr’s recall was “nil”. He was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s.

Nonetheless, Fred refused to relinquish his control of the company. “It was impossible for him to walk away,” Fred III writes. “Work was Fred Trump.” So Donald, along with his brother Robert, came up with an elaborate scheme. They figured out a way to pretend to him that he was still in charge of the company.

Fred Sr was still dressing for work in his three-piece suit, being driven by his chauffeur to the same low-lit, square Brooklyn office with the Native American busts where Mary used to play. It was Goodbye Lenin, but for capitalism.

In May of 1995, with what the New York Times describes as “an unsteady hand”, Fred Sr finally signed power of attorney over to Robert. Within six months, Donald and Robert had begun transferring the vast majority of the property empire to themselves, using various structures and trusts to gain ownership without paying a dollar in estate taxes.

Fred Sr’s will was eventually rewritten with the three surviving Trump children as executors, and with Freddy’s children still essentially cut out. Donald Trump denies allegations of coercion, and the lawsuit was settled out-of-court under a nondisclosure agreement in 2001.

Tax documents unearthed by the Times revealed that when Fred Trump Sr died, he had just under $2m in the bank. In 2004, five years after Fred Sr’s death, the Trump children sold most of the company to an NYC landlord named Ruby Schron for just over $700m.

Today, as an increasingly isolated Donald Trump sits in the White House making increasingly deranged pronouncements online while Elon Musk and his DOGE operatives flock around him dismantling the federal government, it is increasingly hard to miss the parallels. Experts in mental health have been raising alarm about Trump’s own clear cognitive decline for years; in November, the World Mental Health Coalition, a group of psychiatric and medical experts led by forensic psychiatrist Brandy Lee, released a statement saying “his repeated public behaviors and speeches demonstrate strong evidence of significant cognitive decline, aligned with common signs of an early dementia.”

A Potemkin Oval Office; Truth Social a Potemkin social media. History repeats: but this time the world itself is at stake.